Bill hated these budget planning meetings. As one of the remaining plant engineers, he’d inherited the ovens. They were the biggest energy hogs and were always the focus of wild “improvement” projects that consistently failed to meet corporate hurdles. Consultants came and went, turning in colorful reports that eventually found their way to some storage box in the corner. Bill sat as far away from the plant manager as possible in the conference room and tried to stay absorbed in his coffee mug.

“This year we’re going to fix the ovens,” proclaimed Steve, the new manager who had moved down from Ohio.

Bill groaned. “That’s a worthy goal, Steve, but we’ve submitted capital requests for projects on those ovens the last five years and not one was approved.”

Steve rattled off some numbers like he was reading statistics off a baseball card. “Fifty percent of plant-wide gas consumption, 10% of total maintenance, and 27% efficiency from our last analysis. That’s something to be proud of.”

Bill tried not to take it personally. He knew the ovens were a concern. He knew those statistics because he’d sent them to Steve last week. “What do you suggest we do differently this year?” he asked.

Steve just smiled and replied: “That’s what you’ll tell us at next week’s meeting.”

Terrific. Now Bill had one week to fix a problem that had been around for the last 15 years. But Steve had done something that made Bill realize he was serious this time. He asked Bill what other projects he had going on and told him to reassign the top time consumers to someone else. This was good and bad; it would give Bill enough time to work on the oven issue, but it also took away his easiest excuse for not getting the job done.

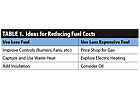

Table 1.

A Journey, Not a Destination

Bill cleared his calendar for that afternoon and found the box of old studies and reports on the ovens. He also avoided his office and hid in the small conference room away from engineering. At first, Bill thought he could recycle some of the old recommendations and narrow them down by finding the one with the shortest payback. He knew that simple payback was easy to figure: Just divide the project initial cost by the annual savings, and the result is the number of years of operation required to earn back the initial investment. But as he thumbed through some of the documents, he noticed that some consultants had used lifecycle cost, while others had used return on investment (ROI). Bill decided that if he was going to do the analysis correctly, he’d better calculate all three values (initial cost, lifecycle cost and ROI) to determine the best way to improve the ovens.Bill found what he’d expected in the reports. The oven efficiency was low but not terrible. The oven could use some insulation repairs, but the estimated savings produced paybacks over five years. Corporate’s standard was two years, and he’d heard rumors that it might drop to one year if profits didn’t improve.

One report had recommended upgrading the controls, so they had found a contractor to install variable speed drives on the fans and link them to the burner controls. Bill knew that the night shift operators put the drives in manual control and then used the old damper system. He had trained several of those guys how to use the system, but with their high turnover rate, he got tired of wasting his time.

Bill really liked the idea of capturing some of the waste heat from the exhaust and using it somewhere else. One of their sister plants had done that with some success. But their arrangement was a little different, and they had been unable to document real savings without the proper metering equipment. So Bill’s previous plant manager had killed the idea for his plant.

Bill’s predecessor had actually done some burner repairs and control upgrades a few years ago, and overall plant gas usage had decreased slightly. But they’d added some water heating capacity and other small gas users about the same time as those repairs. And of course, gas prices had increased dramatically since then, so expenses went up even though usage decreased.

After all his reading, Bill basically figured out that he either had to use less fuel or use less expensive fuel in order to reduce costs. Late that afternoon, Bill made a quick table (see Table 1) and then noticed it was time to head home.

On the drive, Bill had a strange thought. Maybe approaching energy efficiency on a project basis wasn’t the right way to think about it. Bill imagined a Zen master telling him in a dreamy voice, “Young grasshopper, energy efficiency is a journey, not a destination.”

Some of the projects he’d read about in those consultant reports were good ideas but had been shot down by some members of the old guard. If Bill was going to see this oven improvement implemented, he would need to educate some of the other engineers and some members of management. He knew that energy management needed to become part of the plant culture so that it had support at all levels if the project was going to succeed.

Money, Money, Money

Bill decided his first step would be to address Steve’s concern: money. They knew their energy bills were too high, and the primary focus of the project was to reduce energy costs. But what other impacts should be included? Would his changes improve quality? They had some parts that needed to be run through the oven twice because they didn’t cure properly the first time. Some parts came out of the ovens with flecks of dust on them that marred the finish, so some touchup was required. How much did those problems cost? And what if by improving the oven performance, they also could increase the line speed? That would certainly make Steve happy.Bill had been around long enough to understand how the money flowed in his plant, and he understood most of the politics. He knew that production topped maintenance anytime, despite his protests. He knew that the energy bills were paid out of a different pot from capital improvements. He also knew that Steve was reasonable and would respond favorably to a well documented and thought out proposal. But it couldn’t hurt to get the production guys on his side. Bill decided to visit them in the morning and confirm that the ovens were the production bottleneck. He could have all the right numbers, but if he didn’t pay attention to the personalities involved, then any improvement could still be squashed.

By the time Bill got back to the plant the next day, he had a plan for the week. Talk to production, quality and accounting; summarize the oven history and the report findings from previous efficiency improvement studies; and list the full benefits of each option, including impacts to quality, line speed and other factors. For each option, he’d make sure to provide a projected payback, lifecycle cost and ROI. Each option would also include a way to measure the changes in energy use through sub-metering.

Despite a few diversions, Bill met with production, quality and accounting and received their input and buy-in before lunchtime. He was part way through reviewing the options, but he was having some trouble linking the costs together and capturing the full benefit of the different alternatives. That’s when he got an e-mail from Chris, the maintenance supervisor.

Chris had participated in a web presentation sponsored by the electric company that focused on managing energy costs in industrial heating processes. His e-mail had the presentation slides and a spreadsheet tool attached. The tool helped capture all the factors that Bill needed: energy costs for different fuels, labor costs and potential savings, and differences in maintenance costs between options. It even accounted for energy from motors and pumps that might be used in the system.

Bill called Chris and offered to take him out to lunch. “If you find a way to reduce my maintenance headaches with those ovens, then I’ll buy you lunch for a week!” Chris exclaimed.

With the new information in hand, Bill continued working on the analysis. The electric heating options outlined in the utility’s presentation were options Bill had dismissed in the past as impractical for his plant. Current energy prices, however, made some of the alternatives viable. He also learned about infrared heating from both gas and electric sources. In the final analysis that included all factors, infrared turned out to be the most economic method to improve the oven efficiency and reduce operating costs.

Bill pulled out the engineering drawings of his coating line that included the ovens. He felt that infrared might also solve another annoying issue. The parts conveyor and oven entrance were about 15 feet off the floor. A strange airflow condition at the entrance caused hot oven air to spill out into the plant. They had tried special doors, air curtains and even looked at some internal baffles for the oven. Each solution either caused more problems or just didn’t work as advertised.

“But if we put infrared preheaters right here,” Bill said pointing to the oven entrance on the drawings, “then we could reduce the fan speed and keep that hot oven air inside the oven.” This would certainly be one of the added benefits listed in Bill’s chart.

Real Tools for Improving Energy Efficiency

Proof in the Payback

“Admit it, Chris,” said Bill, “you had your doubts it was ever going to work.” Chris looked thoughtfully at his blue plate special. “I did. But you had done your homework. You know what really convinced me? It was that day Mr. Quality came in to the meeting and couldn’t stop talking. All he ever did before was complain to the rest of us and show his fancy charts. That demo you arranged really convinced him. And when he got on board, the whole dynamic of those meetings changed. I’m not sure why, but maybe others felt that he was hardest to convince, and if ‘Bill convinced him then it must be worth it.’”And Chris was right. Eighteen months ago, the numbers were there to make the business case for the oven improvements, and the estimated project payback was even good enough for corporate. But Bill still felt a little uncomfortable with some of the salesman’s promises, so he arranged a demonstration of the infrared heaters on their product line. The vendor brought by some equipment, set up on their line and actually cured some of their product. The performance really resonated with some people who apparently just needed visual proof of performance.

And of course, the project had some setbacks. The electrical contractor went out of business right before their installation. What a headache that had been. Then once it was finally installed, some of the infrared heaters seemed to work sporadically. It turned out that they had been damaged during shipment but nobody had noticed.

“The thing about this project that really made a difference,” said Bill, “was insisting on those new gas meters. If we hadn’t accurately measured the energy usage before the changes and then again after the changes, we wouldn’t know how much we had saved since we had all those other changes in the plant during that time.” After six months of running the new infrared preheaters, Bill had been able to reduce gas usage dramatically and provide documentation of the improvement.

They stood up to leave. Chris picked up the check, did some mental math and then dropped a $50 bill onto the table.

“Is that the tip?” exclaimed Bill.

“Yeah,” said Chris with a sly smile on his face. “I didn’t tell you this, but Steve agreed to pay for our lunch to say thanks for your successful project. So even though I brought you to the diner, I’ve still got to spend Steve’s money.”

Bill smiled. “That’s fine. Next time, though, I’m ordering dessert.”

For more information about improving energy efficiency, visit www.advancedenergy.com.

Report Abusive Comment