Channel Strategy for Architectural Paint in the New Century

Credit: Orr & Boss

Credit: Orr & Boss

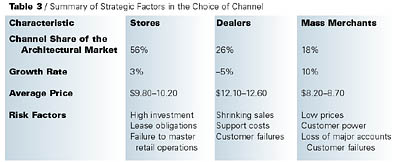

Choice of the right channel involves many more strategic factors than volume, growth rate and gross profits. When forming channel strategy, the coatings company must assess the risks inherent in each channel. It is also necessary to gauge the company’s core competencies objectively. Each of the three main channels demands different skills. The complexity and interaction of these five factors — volume, growth rate, price, risk and expertise — explain why there is no simple “one size fits all” distribution channel strategy. Every company needs to assess its own position and determine the strategy that suits it best.

E-commerce has raised a series of new questions that make choosing distribution channel strategy even more complex and risky than usual. The success of Amazon.com in capturing 8% of the book market in five years suggests that the Internet will quickly affect the way certain specific customer segments select and order paint. In fact, one can already order paint at sites such as paintcity.com, oldsalempaint.com and ourhouse.com.

However, the product still must be delivered, and, as Amazon’s widening losses show, that may well be the fundamental weakness of retail e-commerce. It is too early to predict how the Internet will affect the order fulfillment process, but it is hard to imagine the current generation of paint sites capturing much of the market. Their product availability and pricing are not adequate. In a recent trial, product prices were within pennies of the usual range for DIY customers paid at mass merchants. Normal delivery took one to five days, depending upon the delivery service chosen. For a single gallon of paint, this added $7.60 for ground commercial delivery and a whopping $40 for overnight shipping. Of course, for larger purchases the shipping dropped considerably, but it was still large.

Two things are certain about the Internet. First, e-commerce will evolve. The next generation will offer better service at lower cost. Thus, the Internet may permanently change the way paint is distributed. Secondly, the Internet will cause painful short-term turmoil in our market. Any channel strategy we develop in the next five years will have to deal with both these issues.

Credit: Orr & Boss

Credit: Orr & BossMarket Size, Structure and Trends

In 1998 the size of the North American architectural paint market was close to 650 million gallons, valued at $6.54 billion dollars. Overall, the market has been growing slowly. The compound annual growth rate in the 1990s was 3.6%. Volume has been growing at 2.5% and price at 1.1% in nominal dollars. When inflation is considered, the average real price of a gallon of house paint has been falling at 1.7% a year.These overall figures conceal considerable differences between the three main distribution channels and the individual companies that serve the architectural market. It is perhaps useful to define these channels clearly before we begin our discussion. For the purpose of this article we will use the definition in Table 1. This is slightly different from that used in a number of other recent studies, which tend to class contractor-oriented independent dealers with paint company owned stores.

As Figures 1a–1b show, company-owned stores are the dominant distribution channel in North America. Over half the architectural paint used on the continent is sold through captive outlets. The remaining volume is split almost equally between mass merchants and independent dealers, with 24% and 23%, respectively, of the total gallons sold. However, in value terms the independent dealers are a much larger segment at 26% of the market vs. the mass merchants 18%. This difference arises because the dealers are, on average, paying 50% higher prices to the paint manufacturer.

In fact, the three channels show distinct differences in the price that the paint company can realize. Averaged over the full product line that they buy, mass merchants are paying the paint manufacturer $8.20–8.70 a gallon for architectural paint. Supplying dealers, the paintmaker can charge more than $12 a gallon on average. Selling through stores, to contractors, the average for a totally different product range remains close to $10 a gallon.

The reason for the dominance of company-owned stores is that they are the most effective channel for selling to paint contractors. As government statistics on paint consumption show that contractors apply from 63–76% of the architectural paint used in the United States, stores are bound to be an important channel.

The successful paint company store attracts the contractor for a number of reasons, including product availability, pack size, job site delivery, early opening hours and credit terms. However, given the high level of product availability contractors demand, the price becomes an extremely important factor.

Credit: Orr & Boss

Credit: Orr & BossThis price differential relies on two factors. The first is the professional discount. Depending on the volume the contractor purchases, he or she will get a discount from the marked retail price. The discount will vary between 25% for smaller customers and 40% for larger contractors. At the 30% rate, the contractor will pay less for a top price point product in a store than in a home center. The home centers surveyed did not offer contractor discounts.

The second factor is the existence of professional- grade products. Typical examples would be Benjamin Moore’s SuperHide and SpecHide; Sherwin-Williams ProMar 200, 400 and 700 series; and PPG’s SpeedHide, SpeedCraft and SpeedPro. These products are formulated to have excellent application properties with adequate long-term performance. Careful price/performance optimization allows the raw-material cost of the product to be reduced. With a lower cost product, and not having to share the margin with a retailer, the paint company can afford to sell low price point products to the contractor at a price that is well below the mass merchants’.

Credit: Orr & Boss

Credit: Orr & BossHowever, Table 2 also makes another point. It is not necessary to own stores to succeed. Valspar and Behr have both shown double-digit growth and solid profitability as successful suppliers to mass merchants. ICI is gaining share in this channel; those gains have helped them return to an acceptable financial performance. In the independent dealer channel, Benjamin Moore accelerated its growth and showed exemplary profitability in the last two years.

On the other hand, owning stores does not guarantee success. Despite successes with the mass merchants, ICI, with the second largest chain on the continent has been struggling in the stores channel. So have many smaller companies that own their own outlets. Stores require a massive investment, and earning a return on that investment demands good brand management, excellent retail operations, and hard selling.

It is very difficult to measure growth rates by channel. There are no comprehensive statistics, and the performance of different players in each channel varies a great deal. However, reasonable estimates can be made.

In the mass-merchant channel, Orr & Boss estimates that paint sales are growing 8–12% a year on average. However, performance is exceedingly variable. Home Depot and Lowe’s are growing their paint sales rapidly, while Sears and K-Mart have lost sales in paint. A steady stream of mass merchants, Hechingers is the most recent example, have gone out of business.

It is clear that successful companies are growing sales through their own stores. Sherwin-Williams’ stores division grew sales by 6.7% between 1997 and 1998, though growth has slowed to 3.7% this year. Duron, Monarch and MAB showed greater growth, partly because of new store openings. However, ICI is said to have lost roughly 15% of sales in the rebranding from Glidden to Dulux. Overall, we believe this channel has been growing from 2–3% a year.

Orr & Boss studies estimate that the dealer channel has been declining from 2–5% a year. However, the worst of the decline, driven by new store openings by the big boxes, is probably behind us. Benjamin Moore, the leader in this channel, is still able to grow by focusing on contractor oriented dealers. However, their decision to buy JC Licht and Janovic is significant. We see them moving deliberately toward a dual channel strategy. In the medium term they will focus on the strongest dealers and allow them to consolidate the channel. Purchases of dealers will provide an exit strategy for Benjamin Moore’s customers while building a stores network. For the foreseeable future, it will be necessary to manage the “Benjamin Moore-owned dealers” at arms length to avoid unfair competition with important customers. If, however, the dealer channel declines still further, it will be possible to convert to a conventional stores operation.

Risks

Each of the three main channels has its own particular risks. With stores, the risk factors are the additional investment and added operating costs. Serving dealers, the short-term factors are the credit risk of failed customers and runaway support costs. In the long term, the risk with the dealer channel is being trapped in a declining segment of the market. The risks of selling to the mass merchants are fairly clear. Prices are low, paintmakers that succeed in this channel must have low costs at every stage in the supply chain. In addition, large chunks of sales can evaporate at the whim of a single buyer. The following paragraphs consider these risks in more detail.Opening stores is a major commitment. The paint company must either buy or lease retail space. Buying stores is a large investment in real estate; leasing implies a five- to 10-year contract with substantial monthly payments. Real estate is only part of the investment. The store will require tinting machines, possibly a color computer, a computer system for billing and inventory management, shelving, fixtures, and an inventory of paint and sundries. In addition, stores take between two and three years to break even, so the losses in the first two years must be included in the investment requirements. Excluding real estate, these investment requirements range from $250,000–350,000 per store.

One way to visualize the risks imposed by the investment in a stores network is to think through a simplified case study. Consider the example of a medium-sized paint company that sells $20 million a year of paint through dealers. Suppose the company decides that it must convert to selling through its own stores due to the weakness of its dealer customers. To make $20 million of sales, it will need roughly 20 stores. Suppose these are opened at 10 per year. With good retail strategy and operations, the maximum cash commitment will be $5.5 million–7 million at the end of the second year. With less skilled management, the deficit will still be piling up in the third year, and could be $1.5 million higher. Thus, the first risk is simply running out of cash. Has the company got the resources and the time to implement a stores strategy?

If the hypothetical company develops the right strategy and good operational skills, the payback will be excellent. Twenty stores should generate more than $2 million a year of profit before central overhead allocation. However, if the company does not put stores of the right size in the right locations, staff them with the right people, stock them with the right products, use the right advertising and promotions, and sell to the right customers, the network may never do much better than break even. Thus the second risk is failing to develop retail operating skills. These are completely different from the skills needed to run a manufacturing operation, so there will be a steep learning curve.

There are two key risks in the dealer channel. First, despite the high prices charged to these customers, few of our clients make much profit in this channel. The reasons for that are the factors we call the four Fs. They are the high cost of Frequent sales calls, excessive Freight charges on small orders, Free promotional materials and co-op advertising, and losses due to customer Failures. The exception is Benjamin Moore. They operate very profitably in the dealer channel. This proves that a paint company with the right core competencies can conquer the four Fs.

This is an area where we expect e-commerce to have a very positive impact. A website and e-mail can be used to promote product, support smaller customers and take orders. This should help us all cut SG&A by controlling the first F, frequent sales calls.

The second risk in supplying the dealer channel is the possibility of being trapped in the position of supplying customers with shrinking sales. The dealer channel has been shrinking overall. Just as in other branches of retailing, the big boxes are slaughtering the independents. However, not all independents are equally affected. The dealers who focus on paint, understand their core customers, have the necessary operational skills and are well financed will survive. In fact, they will emerge from the next five years of shakeout even stronger than they are now. Paint companies that want to succeed in the dealer channel must be able to identify these dealers and win their business.

The three main risks associated with supplying the big boxes are fairly easy to see. First, can the company make an adequate profit at the prices these customers pay? When assessing profitability, remember to take into account the additional costs of doing business with these customers. Will you be paying the freight, providing merchandising services, or supporting their advertising?

Secondly, major retailers prefer to be a substantial proportion of the total sales of a supplier. That gives them power in contract negotiations. It also means that losing a single account reduces sales significantly and may jeopardize total profitability or even survival. Home Depot’s recent decision to eliminate regional suppliers is an excellent example of this risk. We estimate this decision cost Duron and Sherwin-Williams roughly 15% of their total sales. Would your profits survive a hit like that?

Finally, retailing is a tough business and it is not just independent dealers who are failing. Many of the big boxes are having a fairly hard time. Supplying a failed home center will result in large write-offs. Hechingers’ failure damaged Sherwin-Williams enough to require a note in the third quarter 1999 financials. It has also hurt PPG. Could your company survive the failure of a customer who might owe you as much as 10% of a year’s total sales?

Credit: Orr & Boss

Credit: Orr & BossConclusion

Table 3 summarizes the key points on volume, growth rate, pricing and risks for the three main channels of distribution for architectural paint. The differences in volume and price show why the right channel strategy has such a large impact on profitability. The growth projections are a warning that our short- and long-term strategies may need to be quite different. The size of the risks underlines the importance of the choice of channel. The diversity of the risks shows that paint companies need to develop very different core competencies to prosper in different channels. This is particularly true when the turbulence that e-commerce will create over the next few years is considered.In part 2 of this article, we will discuss the way distribution strategy influences the core competencies a paint company needs to succeed, and outline the process we recommend for determining the optimum channel strategy.

For more information on distribution channel strategies, contact Orr & Boss, 44450 Pinetree Dr., Suite 103, Plymouth, MI 48170-3869; phone 800/869.9401; fax 734/453.4320.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!