Nanonail Repellents

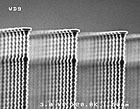

Sculpting a surface composed of tightly packed nanostructures that resemble tiny nails, University of Wisconsin-Madison engineers and their colleagues from Bell Laboratories have created a material that can repel almost any liquid.

Add a jolt of electricity, and the liquid on the surface slips past the heads of the nanonails and spreads out between their shanks, wetting the surface completely.

The new material, which was reported recently in Langmuir, a journal of the American Chemical Society, could find use in biomedical applications such as ‘lab-on-a-chip’ technology, the manufacture of self-cleaning surfaces, and could help extend the working life of batteries as a way to turn them off when not in use.

Silicon “nanonails,” created by Tom Krupenkin and J. Ashley Taylor of UW-Madison’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, form the basis of a novel surface that repels virtually all liquids, including water, solvents, detergents and oils. When electrical current is applied, the liquids slip past the nail heads and between the shanks of the nails and wet the entire surface. The surface may have applications in biomedical devices such as “labs-on-a-chip” and in extending the life of batteries. Images courtesy of Tom Krupenkin.

“It turns out that what’s important is not the chemistry of the surface, but the topography of the surface,” Krupenkin explains, noting that the overhang of the nail head is what gives his novel surface its dual personality.

A surface of posts, he notes, creates a platform so rough at the nanoscale that “liquid only touches the surface at the extreme ends of the posts. It’s almost like sitting on a layer of air.”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!