From Evolution to Innovation

“Our whole universe was in a hot, dense state. Then, nearly 14 billion years ago expansion started. Wait.”1 Wait……the topic of this paper is not The Big Bang Theory (or the lyrics to the theme song from the popular TV show of the same name), but rather our views, or “theories,” on drivers and trends in the coatings industry. While man-made coatings are not quite as old as the beginning of the universe, humankind was known to utilize paint to decorate their caves over 40,000 years ago. Humans and, along with us, coatings, have changed quite considerably since that time. While this article does not cover all factors impacting the coatings industry, we will take a look at three major points: coating technologies and the regulatory landscape, globalization and changing market dynamics, and human performance capabilities.

Coating Technologies and the Regulatory Landscape

Coatings Technology and Types

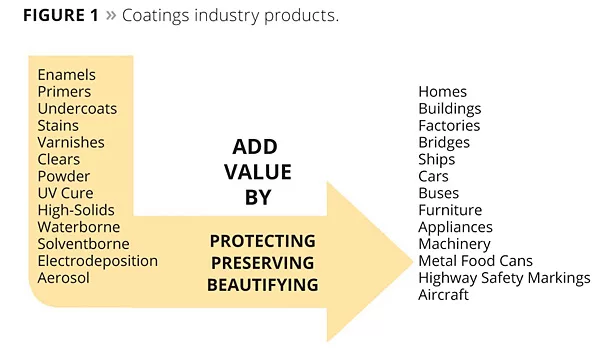

Coatings have long served both beautification and decorative functions. However, today’s coating demands are drastically different than demands in the past. Modern coatings enhance the value of many things from homes and offices to automobiles, military equipment and marine vessels. We must understand the value proposition that modern coatings bring forth. These coatings act by protecting, preserving and beautifying. As seen in Figure 1, there are a number of different technologies employed that protect, preserve or beautify.2

The protective value provided by these coatings is as important as the decorative function. There are numerous examples of the enhancements offered by this protective nature. One example is the chemical, stain and scratch resistance of protective clearcoats on plastics, furniture and automobiles. Another example is the protective characteristics of zinc-rich primers, epoxies, silicone hybrids and polyurethane coatings for steel structures like bridges, oil platforms, tanks, pipes and marine vessels. Depending on the technology, it can provide the necessary corrosion resistance as well as other properties such as chemical resistance and weathering.3

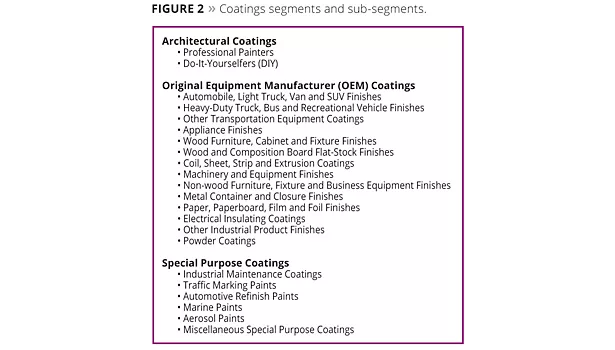

Although we have already covered the value of coatings for protection, preservation and beautification, it is important to truly understand the different types of coatings and how they are classified. For the purpose of this article, we will utilize the classifications consistent with the U.S. Census Bureau as well as the American Coatings Association.4,5 These classifications are comprised of architectural, industrial/original equipment manufacture (OEM), and special purpose coatings.

The segments and sub-segments are much more expansive, as they represent 60 different classifications. Figure 2 illustrates how expansive the coatings market is.4,5,8

The U.S. market represents approximately $18.024 billion with an associated volume of 1.2 billion gallons. Of these segments, the U.S. architectural market has a value of $8.8 billion with a volume of 652 million gallons. The industrial or OEM market has a value of $5.3 billion with a volume of 331 million gallons. The special purpose coatings market has the remaining value of approximately $3.9 billion with 170 million gallons.4,5

New Developments and Technology Shifts

Despite global economic conditions, there continues to be a significant investment in research and development as it pertains to new technology developments in the coatings industry. Technological innovations range from incremental developments to open innovation and partnerships between universities and corporations. Examples of some of these incremental changes can be formulating to lower VOC levels for architectural coatings or improving pot-life and dry time of industrial coatings. However, some of the most dramatic developments come from the technology jumps such as functional coatings with self-healing or super-hydrophobic characteristics.

The drivers for technology development fall into popular themes such as:8

- Government regulation – both domestic and European;

- Cost reduction through lower-cost materials and more efficient processes;

- Energy and fuel savings;

- Preservation of the environment;

- Corrosion protection;

- Improved adhesion to new and various substrates;

- Durability and weathering.

One segment of development that is growing at a rapid pace is the realm of smart coatings. According to a report from the industry analyst firm NanoMarkets, the global market for smart coatings will grow from $363 million in 2013 to almost $3 billion in 2018. Smart coatings are finding new application and fall into the themes above to include coatings for construction, energy, automotive, medical, optics, consumer electronics and military.6

One of the largest segments within smart coatings is the self-cleaning market. The functional nature of self-cleaning is already in place for glass coatings. However, advances in anti-fog and anti-glare coatings will continue to improve the properties of these glass coatings. Other fast-growing areas for self-cleaning include non-glass substrates such as plastics, aluminum, siding, tile and even textiles.6

Significant areas of development are evident in a number of other technology transformations. Nanotechnology is certainly an area in which investments are taking place. Targets for improved coatings using nanotechnology include: optical transparency, corrosion resistance, thermal resistance, scratch and mar resistance, moisture-barrier properties, and durable coatings that can be applied as very thin films. The interest in nanotechnology continues to increase even as health concerns over small nanoparticles are being scrutinized both by organizations and governments.

Some segments of development may be looked upon as “impossible” or “The Holy Grail.” However, significant advancements have been made with situations such as reversible crosslinking or making one-component systems perform as well as two-component technologies. Self-stratifying coatings, super-hydrophobic coatings, super-hydrophilic coatings, conductive coatings, drag reduction coatings, and IR-reflective coatings are all avenues of current development. The development of coatings once deemed “impossible” seems to be now within our grasp.

Also, incremental changes in technology should not be overlooked. Some of these incremental changes are a result of cost reduction. One such example for cost reduction could be the use of filler pigments or spacers to offset the cost of titanium dioxide. Another example of an incremental change is coatings that result in lower VOC emissions. Examples of this include high-solids resins for industrial coatings or next-generation vinyl acetate ethylene (VAE) or acrylic resins for architectural paints. A final example could be utilizing “green” or sustainable raw materials to improve the environmental footprint, such as alkyl phenol ethoxylate (APEO)-free or formaldehyde-free materials.

Regulatory Landscape

Much of the environmental landscape has not changed in the scope of what is of industry concern. Clean air and emissions, heavy metals, lead, and chemical safety hazards were present 50 years ago. What has changed is the level to which the industry has adopted these issues.

Government regulations continue to be a legitimate concern when formulating compliant coatings. Some of these concerns arise from each country having their own version of chemical regulations. Some of these country specific regulations are:

- U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA);

- European Inventory of Existing Commercial Chemical Substances (EINECS);

- Europe’s Registration, Evaluation, and Authorization of Chemicals (REACH);

- Canada’s Domestic Substances List (DSL);

- Japan’s Existing and New Chemical Substances Inventory (ENCS);

- Australian Inventory of Chemical Substances (AICS);

- Korea’s Existing Chemicals List (ECL);

- Philippines Inventory of Chemicals and Chemicals Substances (PICCS);

- China’s Inventory of Existing Chemical Substances (IECSC);

- New Zealand Inventory of Chemicals (NZIOC); and

- Taiwan’s National Existing Chemical Inventory (NECI).

A few of these inventories are being reworked to enforce new rules and possibly more stringent legislation. One example of this is the TSCA Modernization and The Chemical Safety Improvement Act. Another example is the upcoming version of the NECI for Taiwan or even the newly developed REACH legislation.7

To complicate matters even more, several U.S. state and local areas have set up their own rules and legislation. Examples of these include: California’s Green Chemistry Initiative, South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD), California Air Resources Board (CARB) and Ozone Transport Commission (OTC). With all these regulations, companies are forced to formulate to the most stringent requirements if they want to have national, much less global, reach.

The good news is this level of legislation enables the formulator to take advantage of these rules to develop a more environmentally friendly system. A prime example of this is formulating for low VOCs in architectural paints. Not only have formulators adapted to once unimaginably low levels of VOCs, but they are formulating well beyond that. Many companies have developed interior architectural paints that are often lower than 50g/L VOC. In some cases, the systems are well below these levels, down to < 5g/L VOC.

Globalization and Changing Market Dynamics

Mergers, Acquisitions and Partnerships

Having looked at some of the technologies and regulatory drivers behind current coatings formulations, investigation of other global trends that have impacted and will continue to steer the industry is important. In the 1960s, the coatings industry had over 1000 paint companies in the United States alone. The industry had many players at that time. Most of these companies focused on either a particular market segment or a specific region of the country. Several large companies did span the country, but the vast majority specialized.

In a growing market, this type of business model was successful. As saturation of the market occurred, it became more difficult for companies to continue growing. Companies were fiercely competing for incremental pieces of business. Small family owned companies might be happy with a sales growth of 2 to 3% annually. But larger corporations, both those that were publically traded and private ones that aspired to be greater, found that limited annual growth unacceptable. In order to outpace the market, these companies began to acquire some of their competitors. By 2011, the face of the U.S. coatings industry had changed and was far more consolidated, as illustrated by the less than 700 companies remaining at that time.

Not only have changes occurred in the U.S. industry, but coatings companies across the world also experienced changing business dynamics. Driven by lower production costs due to labor, raw material and ease of transportation, offshoring by U.S. and other first world countries’ goods producers became widespread. OEM, automotive, marine, furniture, electronics as well as a variety of other consumer goods are examples of manufacturers that moved production offshore in years past. As these manufacturing activities moved across the world, the U.S. coatings industry had to find a way to supply these customers in their new locations.

This resulted in coatings companies setting up operations in areas such as Mexico and later China. These operations were able to support and protect their current business. They also offered the opportunity to get new business in these emerging markets.

For smaller coatings companies, they often sought out partners in the foreign region. They negotiated paint manufacturing deals and sometimes product licensing arrangements. This brought novel technology into their home market and allowed them to enter new market areas with minimal financial investment.

The mid to late 2000s saw a surge in coatings companies making deals. Many of these purchases gave the buyer a footprint in a market region outside their home base. Some of these deals included:9

- Akzo Nobel merged with ICI;

- Valspar bought Teknos Nova Coil;

- PPG purchased SigmaKalon Group;

- Sherwin-Williams acquired Arch Chemicals’ industrial wood coatings;

- Akzo Nobel bought ChemCraft Holdings;

- Akzo Nobel’s International Protective Coatings division bought CeilCote;

- PPG bought assets of Champion Coatings;

- Sherwin-Williams acquired NAPKO;

- Becker Industrial Coatings acquired Specialty Coatings;

- Becker Industrial Coatings acquired Sherwin-Williams’ North American coil coatings;

- Akzo Nobel acquired Solient;

- Consorcio Comex S.A. de C.V. acquired Para Paints and Duckback;

- Fujikura Kasai acquired Red Spot Paint & Varnish;

- PPG acquired Akzo Nobel Architectural (U.S.);

- Sherwin Williams acquired Comex (U.S. and Canada).

These expansions into existing or new markets gave companies the opportunities to not only protect current business and existing customers but to also prospect for new opportunities. They gained technology and expertise that could then translate back into their home market and increase sales with their traditional customer base.

Cultural Challenges

These acquisitions and many others brought not only equipment to the buyer’s organization, but it also brought people and know-how. Coordination and cooperation among these often times disparate groups is a major challenge that companies face.

“Culture shock” has been a phenomenon that cropped up in many of these organizations and has two major components. The first is the impact on organizational functionality. This culture shock might be the difference between how an American and a European company operate. Understanding how each operates, respecting those differences and learning to make these differences strengths, not weaknesses, are a hallmark of successful organizations.

The second type of culture shock commonly experienced is when an established, large corporation acquires a small entrepreneurial company. The employees from the small company can feel constrained and slowed by the business practices within their new organization. Learning to harness and focus these competing cultures is quite difficult. The likelihood of the company merger being a success increases substantially if the cultures can be successfully merged.

It was also not unusual to find different locations of the same company working on the same project. The need to address this issue has also been exacerbated due to mergers and acquisitions. In essence, internal divisions within a company were competing with each other. While competition can be a positive motivator, in a resource-constrained environment, multiple groups working on a single project means other opportunities are not being given a full complement of resources. This diminishes the chance for success of the project. The coatings industry has continued to evolve organizationally to address these issues

Shale Gas/U.S. Industry Reshoring

Hardly a day passes without an article about shale gas or the announcement of an ethane/ethylene cracker greenfield project or expansion. While few, if any, articles at this time directly link shale gas with coatings, the potential for this phenomenon to drive positive growth in our industry is perhaps unparalleled in recent history. Shale gas is the impetus needed to kick-start the U.S. economy and drive increasing demand for coatings.

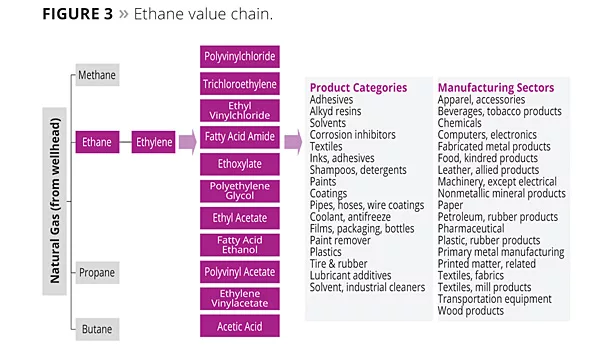

The U.S. has identified drillable shale gas reserves that fall second only behind China in volume. However, the quality of the reserves (i.e., higher ethane content) and the cost basis as well as the required infrastructure for drilling in the United States is rivaled by none. Shale gas feeds the ethane value chain, which is the basis for the fundamental raw materials for 96% of the manufactured goods we use every day. Just a few examples of those goods are adhesives, textiles, plastics, resins, solvents and, of course, coatings (Figure 3).10

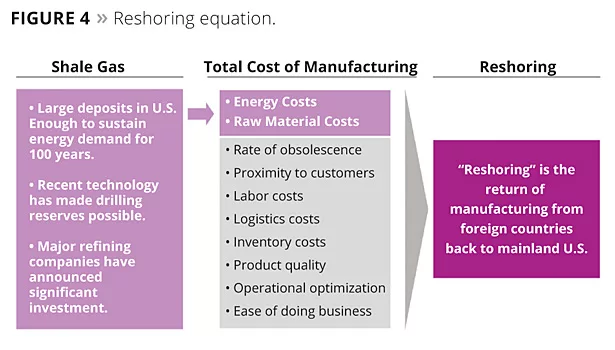

All major petrochemical manufacturers have announced plans to expand cracking capacity. The impact of the availability of ethane chain products on raw material cost for the aforementioned industries as well as for energy costs is expected to be a benefit for manufacturers. However, the biggest expected impact of shale gas on the U.S. economy is the already announced as well as expected reshoring of U.S. businesses from overseas. Reshoring, which can also be referred to as inshoring, is the return of manufacturing from foreign countries back to the mainland United States. Reshoring is being driven by shale gas, which is positively impacting the total cost of manufacturing goods by reducing energy costs as well as raw material costs. The catalyst in the reshoring equation is the changing “rate of obsolescence” especially for electronic goods. We can all testify to the fact that new technology such as cell phones, tablets, televisions and computers has a much shorter life-span than in the past. Customers demand faster responses from industry in regard to new product development, which drives other reshoring factors such as proximity to customers, logistics costs, ease of doing business and inventory costs. Finally, rising labor costs outside of the United States, unpredictable foreign product quality and operational optimization needs have all exhibited recent trends towards favoring U.S. production facilities. Lower total manufacturing cost makes investment in the United States more attractive (Figure 4).10

Studies indicate that 37-39% of U.S. manufacturing companies plan or consider reshoring production either through expansion of existing, mothballed or greenfield production facilities. Companies such as Ford, Caterpillar, Apple, GE, GM, and a wealth of others have already made announcements regarding renewed or expanded production plans in the Unites States (Figure 5).10

A projected 25% increase in ethane supply is expected to drive a $16 billion capital investment for new petro-chemical and derivatives capacity. This increase in capacity prompts downstream investment of $72 billion in industries like paper, chemicals, plastic and rubber, glass, iron and steel, foundries, and fabricated metal. More workers will be needed in those industries at a rate of 1.2 million sustainable jobs. This value chain creates $135.6 billion in direct and induced output as well as an estimated $26.2 billion in annual federal, state and local tax revenue.10 Those numbers sound impressive, but how does this directly impact our industry (Figure 6)?

The shorter- to medium-term impact will include coatings required for plant restarts, rehabilitations and new construction. Coatings manufacturers should also experience an improvement in raw material cost position for ethane-based raw materials. An increase in demand is expected for coil, industrial, plastic, automotive and wood coatings.10

Sustainable employment will drive a longer-term impact by release of the pent up demand for goods that has stalled due to the past few years of economic downturn and high unemployment rates. In short, people will have jobs and will be able to afford new cars. They will also be willing and able to repair and refurbish houses or buy new properties. Consumer spending will increase, and demand for architectural as well as other coatings types will improve as a consequence.10

Shale gas and reshoring are already making headlines in the news and creating discussions in boardrooms. However, one should be aware that government environmental policy could act as a detriment to the shale gas expansion, but we should be prepared as an industry to leverage the growth driven by this phenomenon.

Human Performance Capabilities

While coatings companies most certainly do not date back to the time of the first cave paintings, it is still evident that many factors have changed since the industry became commercial in the 1700s.

Harvey S. Firestone once said, “Our company is built on people – those who work for us, and those we do business with.”11 Firestone placed an emphasis not only on his customers but also on the people who comprised his workforce. Changes within a company’s workforce can have tremendous impact – both positive and negative – on business performance.

Industries, including our own, are acknowledging and implementing practices aimed at understanding the influence of generational differences across the workforce. Today’s employees span four different generations – the Matures (born 1927 to 1945), Baby Boomers (1946-1964), Generation X (born 1965 to 1975), and the Gen Y also known as the Millennials (born late 1970s to 2000). The generational expert, Cam Marston, delivered a keynote address at a conference organized by PPG, stating that “understanding generational differences can ease workplace frustration while increasing teamwork and productivity. For example, most Matures and Boomers value their work ethic and job commitment, while Gen Xers’ and Millennials’ primary identity is outside the workforce. That doesn’t mean one generation is more productive than another, just that each has its own way of doing things and that tailoring communications to reflect these distinctions is the key to success.”12

Accenture defined the implications of changing workforce demographics as “Interactive Effects of Human Performance Process” as seen in the representation in Figure 7.13

With a combination of knowledge transfer initiatives, employee retention programs and effective recruiting for new talent, businesses in our industry can tailor a program to address their specific workforce needs in order to meet long-term business objectives and optimize human performance capabilities.

Knowledge Transfer

Knowledge transfer is becoming a bigger issue each year in the chemical industry. Studies suggest that thousands of Baby Boomers are retiring each day and will continue to do so. Every day, approximately 10,000 Baby Boomers reach the age of 65. This trend is expected to continue for approximately the next 20 years. “In 1990, 11.9% of the labor force was 55 and older. Over the 1990-2000 timeframe, the share of the older labor force increased to 13.1%. In 2010, the share increased again, to 19.5%. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that the share of the 55-year-and-older labor force will increase to 25.2% in 2020.” Baby Boomers comprise nearly 40% of the current workforce. While the recent years’ economic downtown has, in some cases, prolonged retirement for some, a large percentage of the workforce will be eligible for retirement in the coming years.14 “You just can’t be as innovative with only young Ph.D.s. The experience really matters,” said Henk Bonourvié, HR manager for the Chemical R&D Institute and Akzo Nobel.13 “What you really lose through people leaving is efficiency – knowledge of how to get a job done faster and better. But, of course, that’s hard to quantify” said William Litschgi, a retired research director from Monsanto.13 This poses a challenge not only for our industry but for the United States as a whole. How do we retain the knowledge and experience of this generation before they leave the workforce and create a knowledge gap or a “brain drain” in the coatings industry? Awareness of this issue within our organizations and targeted knowledge retention programs can help stem the flow of that expertise out the door. Unfortunately, there is no easy answer to address this looming problem.

Many of these programs contain elements such as career development and succession planning. While this may seem like a straight-forward solution, most of us can relate to situations where skilled employees have retired and their knowledge was in no way collected or passed on to a younger employee. It also addresses a potential safety component. Having to fill posts vacated by experienced workers with less-experienced ones who may not have had time for proper training, opens the door for safety concerns and workplace incidents.

Another tool employed to retain knowledge is IT. With the advent of shared network drives, intracompany forums and platforms, plus a myriad of other IT options, we have the flexibility now to capture data in ways that were not available when even the youngest of the Baby Boomers and the oldest of the Gen Xers started working. An issue related with this methodology is that not all Boomers are comfortable or savvy with technology and do not prefer to share knowledge in this way.

In 2010, Dr. Stephen F. Barnes from the San Diego State University Interwork Institute stated that “only about a third of private sector employers have specific plans to retain their older employees…” He believes this is related to entrenched biases as well as “legal and policy barriers.”15 However, some businesses have started the practice of bringing retired employees back as contractors. This can be positive in exceptional cases, but should probably not be instituted as a standard platform for any company without first assessing the inherent risk and potential unwillingness of pre-retirement employees to share info in the hope that they have a later shot as a contractor.

In some cases, mentorship programs have proven to be successful, but these can also be challenging and time-consuming. In clear succession situations, it may be ideal. However, caution should be taken in establishing broad-based mentorship programs with no clearly established goals. “We’re never going back to the protégé/mentor model and the cast of thousands where less-experienced people all have mentors,” said Ron Carrick, Business Information Manager in DuPont’s engineering organization. “We can’t afford that in time or money, and we can’t get that many people.”13

Another interesting option is creating diverse work teams to tackle company projects. By creating multifunctional teams that span age, educational background, gender, race and functional areas among others, knowledge transfer can be handled quite effectively if the team is properly organized and integrated in the business.

These are only a few of the many ideas that can be used individually or collectively to stem the “brain drain” associated with the retirement of experienced, knowledgeable employees. A researched, targeted and strategic platform with a variety of programs to combat the problem can lead to a successful approach.

Recruiting and Retention

While having to balance the potential effects of the “silver waves” of retiring Boomers, we also need to understand the impact of our multi-generational workforce and the influx of Millennials, also known as the Gen Yers, into today’s business world. Those very Baby Boomers who are already retired or who are contemplating retirement sired the Millennials. The oldest of the Millennials have just started their careers in the last years, and their entry in the workplace has already caused waves of a different sort.

The Millennials “have never bought vinyl nor had a roll of holiday snaps developed and would think it is crazy to call a group of friends to arrange a night out when a post on Facebook will suffice.”16

- 50 – the average number of text messages teenagers send every day.

- 29 – percentage of Millennials who think work meetings are an efficient way to determine a course of action. This is in comparison to 45% of Boomers.

- 27 – the approximate percentage decline in email usage among those ages 12-34 over the past year.

- 41 – the percentage of Millennials who have made a purchase using their smart phone.

- 48 – the percentage of Millennials who said word of mouth influences their product purchases more than TV ads. Only 17% said a TV ad prompted them to buy.

- 20 – the percentage of the Millennials who are Hispanic…more than any generation before them.

- 21 – the percentage who said helping someone in need is one of the most important things in life.17

This list could go on and on from topics ranging from environmental awareness and community service to views on religion, politics and marriage, but it is a start at showing the difference between this generation and those preceding it. The obvious change in modes of communication, technological savviness, diversity and purchasing behavior - just to name a few – show a shift in priorities and the need to recruit and retain talent from this generation using a different focus than in years past.

Unfortunately, this generation is commonly seen by members of the older generations, such as the Gen Xers, Baby Boomers and the Matures, as entitled and pampered with unrealistic career expectations. Regardless of one’s personal views regarding this group, at approximately 75 million people, they rank a close second in size only behind the Baby Boomers. They currently comprise approximately 25% of the total U.S. population and are estimated to comprise 40% of the workforce by 2020,14 and they will be a force to be reckoned with in the business world. The Millennial generation is the industry’s hope to replace the workforce gap left by the retiring Boomers. It must also be noted that they bring a lot of skills to the table that should be recognized and utilized.

The burning question is how do we attract and retain this talent to our businesses? Recent studies show that more than half of the graduating class of 2010 from University of Pennsylvania and 49% of the same class at Harvard are working in either finance or consulting. Paul Kedrosky, an economist with Kauffmann Foundation, indicates that this trend has been evident for the past two decades. Kedrosky notes that a more recent change, however, has been the draw of scientists, engineers and mathematicians into the financial sector.18 That is a trend that definitely impacts the availability of top raw talent for the coatings industry.

Unfortunately, this trend is not the only one that is negatively affecting the ability to successfully recruit talent. Several others, such as the impact of the recent economic downturn on recruiting activity and potential lack of advancements in recruiting technology, have hurt some chemical businesses.

The chemical industry also suffers an image problem. It is noted that some Millennials may see the industry as environmentally unfriendly and less appealing than other industries such as finance.13 The industry has also traditionally been seen as a homogenous make-up of people without much diversity.13 Many of these factors have improved in the recent past, but most likely, work still needs to be done to encourage young graduates to join our companies. Few would argue that the U.S. coatings industry will continue to need strong research and investigative skills as well as business, HR and marketing skills to remain competitive on a global basis and to continue to meet the ever-growing demands of our customers.

While these are not easy topics that can be addressed with a wave of a magic wand, the culture of relationships with businesses and universities, including interaction with students, has changed. In 1961, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stated in his farewell address to the nation, “The free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by federal employment, project allocations and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.” In that era, students protested across campuses against military and corporate presence. Recent times have shown a far different approach and acceptance to industry partnerships with universities. “The industry-academic hook-ups are responsible for new courses such as polymer engineering and green chemistry…The partnerships have reinvigorated basic chemistry and chemical engineering departments and are improving the skills of scientists entering the work force.”19 The chemical industry’s presence at universities through R&D programs, branding initiatives, scholarship and sponsorship opportunities, and recruiting fairs does and will hopefully continue to encourage top talent to this industry.

Once Millennials have been recruited to a company, it is important to create a culture that integrates and energizes them with those of other generations, which means challenging them, providing plenty of feedback, cross-training to build competencies, and developing clear-cut paths, writes Dr. Joanne G. Sujanesky. It should be noted that these are not only tactics that are successful with Millennials but that can also be employed across the entire spectrum of the workforce.20 What must be particularly noted is the methodology and communication tools and style by which managers take up this practice with the Millennials.

What do Millennials want out of a job? While it is not accurate to force stereotypes on all individuals who compose this group, it is fair to make some general comments about overarching views. Millennials want job structure that includes proactive guidance from their supervisor as well as milestones for their work. They also like to understand how their work fits into the big picture of the organization and reaching strategic goals. Millennials grew up with Baby Boomer parents who gave them lots of feedback. That has also carried over into the workforce. Feedback is typically appreciated by Millennials in a specific, straightforward and timely manner. Another aspect that resonates keenly with this group is the ability to have flexible work schedules or the option to work from home. As stated earlier, this generation values work/life balance and would like to see that their job offers them the flexibility to manage that.21 They also have high expectations of career advancements, and statistics show that 70% leave a new job before the first two years.22 Companies who strive to challenge their younger employees create career ladders or advancements in place are able to retain Millennials longer.

When one considers retirement of the older generations as well as influx of new employees, the challenge is to effectively bridge the chasm between generational differences that prefer knowledge transfers in different formats. While the Boomers may prefer mentorship programs, the Millennials are most likely comfortable with IT-based knowledge sharing. The industry and our individual companies should have programs that span both the needs and preferences of not only the Boomers and Millennials but all members of the organization to effectively reach long-term strategic goals.

Survival of the Fittest

Scott Adams, the creative genius behind the Dilbert comic strip, once wrote, “Large corporations welcome innovation and individualism in the same way the dinosaurs welcomed large meteors.” On a serious note, the coatings industry continues to face challenges both externally and internally, but also has the ability to grasp some real growth opportunity through technological capabilities, global drivers and U.S. economic potential, and talented employees. n

References

1 Barenaked Ladies, Lyrics.time, The Big Bang Theory Theme Song, http://www.lyricstime.com/barenaked-ladies-the-big-bang-theory-theme-song-lyrics.html (December 13, 2013).

2 American Coatings Association, The Value Added by Paints and Coatings, http://www.paint.org/about-our-industry/coatings-add-value.html (December 13, 2013).

3 Munger, Charles G. Corrosion Prevention by Protective Coatings Book, National Association of Corrosion Engineers, 1999, Houston, Texas, 510.

4 U.S. Census Bureau, 2011, Current Industrial Report MA 325F, https://www.census.gov/manufacturing/cir/historical_data/ma325f/ (December 13, 2013).

5 American Coatings Association, Types of Coatings, http://www.paint.org/about-our-industry/types-of-coatings.html (December 13, 2013).

6 Report Predicts Smart Coatings Market to Reach $3 Billion by 2018, PCIMagazine, 2013, http://www.pcimag.com/articles/98468-report-predicts-smart-coatings-market-to-reach-3-billion-by-2018 (December 13, 2013).

7 Keller and Heckman LLP, 2013, TSCA Reform Center, http://www.khlaw.com/resources.aspx?show=TSCA (December 13, 2013).

8 American Coatings Association and The ChemQuest Group, Inc., U.S. Paint & Coating Industry Market Analysis (2010-2015), 820.

9 Milmo, S. Merger and acquisition report, Coatings World Magazine 2007, http://www.coatingsworld.com/contents/view_europe-reports/2007-12-19/merger-and-acquisition-report/ (December 13, 2013).

10Yosh, J.P. Shale Gas, Reshoring & Its Impact on the Coatings Industry, 2013, 20.

11 Firestone, H.S. Brainy Quote, Harvey S. Firestone Quotes, http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/h/harvey_s_firestone.html (December 13, 2013).

12 PPG Industries, Expert says understanding generational differences helps success of collision operations, http://www.ppg.com/en/newsroom/news/Pages/20100422.aspx, 2010, (December 13, 2013).

13 De Long, D.W. and Accenture, Confronting the Chemical Industry Brain Drain: A Strategic Framework for Organizational Knowledge Retention, 2002, 15.

14 Toossi, M. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment outlook: 2010-2020, 2012, http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2012/01/art3full.pdf, (December 13, 2013).

15Barnes, Ph.D., Stephen F. and San Diego State University Interwork Institute, 2010,

The Future of the American Workforce, http://interwork.sdsu.edu/elip/bve/documents/FutureoftheAmericanWorkforce.pdf (December 13, 2013).

16 CSC, CSC Smart Business UK Edition February – Attracting Millennials, http://www.csc.com/smart_business/publications/94486/94633-csc_smart_business_uk_edition_february_attracting_millennials (December 13, 2013).

17 Abraham, A. Edelman Digital, 2011, By the Numbers – 50 Facts About Millennials, http://www.edelmandigital.com/2011/06/01/by-the-numbers-50-facts-about-millennials/ (December 13, 2013).

18 NPR, 2012, Stopping the “Brain Drain” of the U.S. Economy, http://www.npr.org/2012/02/05/146434854/stopping-the-brain-drain-of-the-u-s-economy (December 13, 2013).

19 Mullin, R. University Inc., Chemical and Engineering News 2013, http://cen.acs.org/articles/91/i31/University-Inc.html (December 13, 2013).

20 Sujanesky, Ph.D., Joanne and Reed, Jan Ferri, Keeping the Millennials, Industry Week 2009, http://www.industryweek.com/articles/keeping_the_millennials_19502.aspx (December 13, 2013).

21 Heatter, T. TDS, Retaining Millennials, http://www.tdshou.com/content/documents/06.Retaining_Millennials_v3_0.pdf (December 13, 2013).

22 Smith, G.P. Chart Your Course International, 2013, Four Keys to Attract and Retain Millennials, http://www.chartcourse.com/four-keys-to-attract-and-retain-millennials/ (December 13, 2013).

This article was presented at The Waterborne Symposium, Feb. 24-28, 2014, New Orleans, LA.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!