Race to the Top: Continued Consolidation in Architectural Coatings

In early 2013, Grace Matthews published a white paper titled North American Architectural Coatings: The End Game? In it, we discussed the recent acceleration in architectural coatings mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and likened the “Big Four” – at the time Sherwin-Williams, PPG, Masco and Valspar – to the final table of a poker tournament. Today, with Sherwin-Williams going “all-in” with its acquisition of Valspar, PPG’s unsuccessful attempt to acquire Akzo, and now with several companies courting Axalta, M&A activity in coatings is heating up again, and we thought it would be timely to review the M&A activity in the North American coatings industry that has taken place in the years since that report was published, and share our thoughts on the outlook.

When we published The End Game in early 2013, Sherwin-Williams was seeking regulatory approval for its proposed $2.34 billion acquisition of Comex, a leading producer of architectural coatings based in Mexico. The transaction was valued around 13x EBITDA. At the time, we described the deal as “the best strategic acquisition of significant size in architectural coatings in recent memory.” The deal was a game changer for Sherwin-Williams, and aligned closely with its strategy to acquire high-quality coatings businesses that enhanced its geographical coverage and/or provided strong brands. Comex clearly checked both of those boxes. While the valuation left little margin for error, we were confident in Sherwin-Williams’ ability to successfully integrate Comex and generate significant synergies. In short, this appeared to be an excellent acquisition and a triumph for Sherwin-Williams in the rapidly consolidating decorative coatings market.

On the heels of the Sherwin-Williams/Comex deal announcement, PPG revealed its plans to acquire AkzoNobel’s North American Architectural Coatings business. The $1.05 billion deal included all of Akzo’s North American paint manufacturing assets, 600 company-owned stores, and access to more than 10,000 points of distribution through national home centers, mass merchants and independent dealers. Importantly, the deal also included key brands like Glidden, Flood and Sico. With the transaction, PPG was set to become a much more formidable competitor to Sherwin-Williams in North America.

However, Sherwin-Williams was stunned in October 2013 when Mexico’s Federal Economic Competition Commission unanimously rejected the Comex deal, stating that the combination would be potentially anticompetitive in that the combined companies would have more than a 50% market share in Mexico. Nevertheless, Sherwin-Williams did manage to acquire Comex’s U.S. and Canadian assets for around $165 million. While viewed perhaps as a consolation prize at the time, these assets have turned out to be a nice addition to Sherwin-Williams’ store base in the United States, and particularly in Canada.

In June, less than four months after Sherwin-Williams formally terminated its bid for Comex, PPG shocked the industry by announcing that it had reached an agreement to acquire the Comex business in Mexico for $2.3 billion, about the same value that Sherwin-Williams had been willing to pay. This time, due to PPG’s limited decorative paints presence in Mexico, the deal was approved by regulatory authorities. In less than two years, PPG had used M&A to become the greatest competitive threat to Sherwin-Williams on its home turf. It was all too familiar for Sherwin-Williams, which seven years earlier had participated in the auction process for SigmaKalon, only to see PPG prevail. How would Sherwin-Williams respond?

As it turned out, in a big and unexpected way. A little over two years later, the coatings industry was caught off guard when Sherwin-Williams announced its intent to acquire Valspar, a deal that would displace PPG as the largest coatings company in North America. We were surprised both by the deal itself and its $11.3 billion valuation (roughly 15x EBITDA), and judging by the conversations we had with coatings industry personnel in the days that followed, so was the industry. Many wondered if this deal signaled a peak in the M&A market or if one was soon approaching. For reference, Sherwin-Williams’ entire market capitalization at the time was around $25 billion, so this truly was a transformational acquisition. Initially, many wondered whether a deal between two global coatings industry giants would be supported by regulatory agencies. Upon closer examination, however, Valspar and Sherwin-Williams had remarkably little direct overlap that would concern regulators. In fact, we believe Valspar was perhaps the only major coatings company that Sherwin-Williams could acquire, as their businesses were more complementary than directly competitive. Still, to obtain the approvals required to close the deal, Valspar was forced to divest its North American industrial wood coatings business, which Axalta purchased last June for $420 million.

Although Sherwin-Williams was most attracted to Valspar for its industrial and packaging coatings and strength in international markets, the incremental $1 billion of architectural coatings revenue represented a key element of the deal. Most of Valspar’s decorative paint revenue is generated through mass merchants, big-box home improvement retailers and independent hardware stores. These channels tend to cater more to “do it yourself” (DIY) customers and small contractors, while company-operated retail stores (a core focus for Sherwin-Williams) are typically designed to serve larger paint contractors. Valspar also brought a portfolio of high-quality brands, include Valspar Paint and Cabot. The Valspar Paint brand is offered through more than 10,000 points of distribution, more than any other North American paint brand, and is expected to remain a focus brand for Sherwin-Williams going forward.

While the Valspar acquisition was huge news, it wasn’t the only recent deal that could prove to reshape the architectural coatings landscape in North America. In December 2016, Nippon Paint, the world’s fourth-largest coatings company with $4.8 billion in global sales, quietly acquired Dunn-Edwards, one of the largest independent architectural coatings companies in the U.S. Dunn-Edwards, which generates annual revenue in excess of $350 million, sells paint through 130 company-operated stores and more than 80 independent dealers, with nearly 90% of sales to professional painters. The deal, which was valued at $608 million, allowed Nippon Paint to enter the U.S. decorative paint market with a platform that, while still dwarfed by competitors like Sherwin-Williams and PPG, has grown into a formidable player in the Southwest and West, and sustains a strong and loyal contractor base. The sale of Dunn-Edwards caught many industry experts, including us, by surprise, as the 91-year-old company had remained independent for so long and had certainly been courted by each of the major U.S. coatings companies (and private equity groups, we imagine) over the years. Nippon represents the best of both worlds for Dunn-Edwards, as it offers a strong balance sheet to support growth while allowing Dunn-Edwards to maintain its brands and continue operating with a high level of autonomy. After completing the transaction last March, Nippon issued a brief statement outlining its goal of using Dunn-Edwards as a base from which to grow further into the U.S. decorative coatings market. We would not be surprised to see Nippon aggressively pursue additional acquisitions in the U.S. to support these efforts. To a potential seller, Nippon’s focus on building a market position may offer a unique alternative to the more consolidation-focused strategy that is often utilized by other U.S. coatings majors.

Another large, potentially transformational deal that at the time of this writing may or may not be in the works is PPG’s recent attempt to buy AkzoNobel, which sold its North American architectural coatings business to PPG four years ago. Last March, PPG extended an unsolicited offer to acquire Akzo for about $22 billion. Akzo’s board rejected that offer as too low, leading PPG to increase its offer twice more, with the last offer valuing the company at about $29.5 billion. Even though PPG had some support from Akzo shareholders, including the activist investor hedge fund Elliott Management, Akzo appeared determined to remain independent. It rejected each of PPG’s offers and proposed instead to increase shareholder value by spinning off or selling its specialty chemicals business, which would have made it more of a “pure play” coatings firm. PPG also faced hostility from Dutch politicians and courts. The Dutch Economic Affairs Minister said the proposed deal was “not in the national interest,” and a Dutch court ruled against PPG in a lawsuit that would have forced Akzo to negotiate with PPG. PPG dropped its takeover attempt in June, and entered into a mandatory six-month cooling off period.

In November, Akzo held preliminary talks with Axalta about a “merger of equals,” presumably in part to discourage PPG from renewing its takeover attempt. Those discussions ended when Nippon entered the picture and made an unexpected offer to acquire Axalta. Shortly thereafter, Axalta broke off talks when Nippon’s board appeared “unwilling” to increase its $9.1 billion all-cash bid. As this article goes to press, the entire situation is unsettled. PPG’s cooling off period ended on December 1, but PPG’s CEO has gone on record that his company is no longer interested in pursuing a deal with Akzo. The latter could attempt to restart negotiations with Axalta. Alternatively, with Axalta “in play,” other suitors could enter the picture. Stay tuned.

Structural Drivers of Industry Consolidation: The Importance of Synergies

M&A in the coatings industry occur for a variety of reasons, but are often driven by the ability for major coatings companies to generate considerable synergies through an acquisition. The word synergy is pervasive in the M&A world; read almost any transaction announcement and you are sure to find the word (perhaps used more than once) before the end of the first paragraph. In all seriousness though, synergies in coatings transactions are real, and importantly, they are quantifiable. The Sherwin-Williams/Valspar transaction offers a clear illustration of the importance of synergies. When the deal was announced, Sherwin-Williams’ management projected approximately $280 million of annual synergies by 2018, which would reduce the implied transaction multiple from about 15x to around 11x EBITDA. The longer-term target was set at approximately $320 million in annual cost synergies. At an investor conference a few months after completing the transaction, Sherwin-Williams increased its long-run annual synergy target to $385-415 million, which was revised to include $65 million of annual revenue synergies and an increased cost synergy target of $30 million. We were not surprised by this update, as Sherwin-Williams has a long and successful history with acquisition integration (21 deals completed over the past 10 years), and we also expected some conservatism to be factored into the initial synergy estimates. Despite its strong strategic rationale, a deal of this magnitude still carries significant risk, and we fully expect Sherwin-Williams will take an “all hands-on deck” approach to the integration in the months and years to follow. As a side note, viewing a major acquisition through the lens of a “pro-forma” EBITDA multiple, which in this case is under 11x after considering synergies, is one of the primary ways a company can justify paying acquisition multiples that seem eye-popping on the surface.

Another example of the importance of synergies involves the target company’s procurement function – which raw materials they are buying, in what quantities and from which suppliers. Why is this so important? Simply put, if the target company is significantly smaller than the acquirer, the acquirer will likely be able to purchase TiO2, resins, additives and other key inputs at better prices. The buyer also may have direct relationships with many key suppliers (instead of purchasing through distributors), and they might even have in-house resin manufacturing capabilities. All of this can add up to significant cost savings after closing. As a starting point, many large coatings companies assume they can reduce total raw material costs by 10% when acquiring a smaller company, and the savings can sometimes far exceed this level.

The ability for a buyer to capture raw material cost savings isn’t limited to smaller bolt-on acquisitions, however. When discussing the Valspar acquisition, Sherwin-Williams has noted that 39%, or $150 million, of the $385 million in projected annual cost synergies is expected to stem from raw material cost savings. A portion of these savings will come from more efficient procurement, partly due to the enhanced scale of the combined organizations – in other words, the ability to negotiate better terms with suppliers. Importantly though, Valspar brings significant resin manufacturing capabilities through its Engineered Polymer Solutions (EPS) division, which should drive additional savings by allowing Sherwin-Williams to produce many of its key coatings resins internally. In-house resin production requires a significant amount of investment and scale to operate efficiently, so it tends to be limited to the major coatings producers. In-house resin manufacturing through EPS was another key benefit of the Valspar deal, and it solidifies Sherwin-Williams’ competitive position over smaller formulators that purchase their resins externally. In addition to supplying Valspar, EPS was a key resin source for a variety of small and mid-sized coatings formulators, and it will be interesting to see if Sherwin-Williams alters that strategy in any way going forward.

In hindsight, the timing of the Sherwin-Williams/Valspar deal was fortuitous in that it occurred during a period when costs for many key raw materials were beginning to increase after several years of decline. Figure 1 presents the monthly U.S. Producer Price Index for Architectural Coatings over the last several years. Interestingly, the data illustrates an increase in wholesale coatings production costs in April 2016, the month after the Sherwin-Williams/Valspar deal announcement. We also see an increase in 2017, particularly in the second and third quarters, coinciding with price increases issued by coatings companies in response to increasing raw material costs.

FIGURE 1 » Monthly U.S. Producer Price Index (architectural coatings) (2014-2017).

While cost increases represent challenges for even the largest coatings formulators, the procurement abilities of the combined Sherwin-Williams/Valspar organization should serve to lessen the blow to some degree, particularly compared to smaller formulators that are less-equipped to raise prices or negotiate with large suppliers. Major formulators also find themselves in a preferential position when dealing with shortages of key raw materials, as experienced last summer following Tropical Storm Harvey, which impacted basic chemical production along the Gulf Coast.

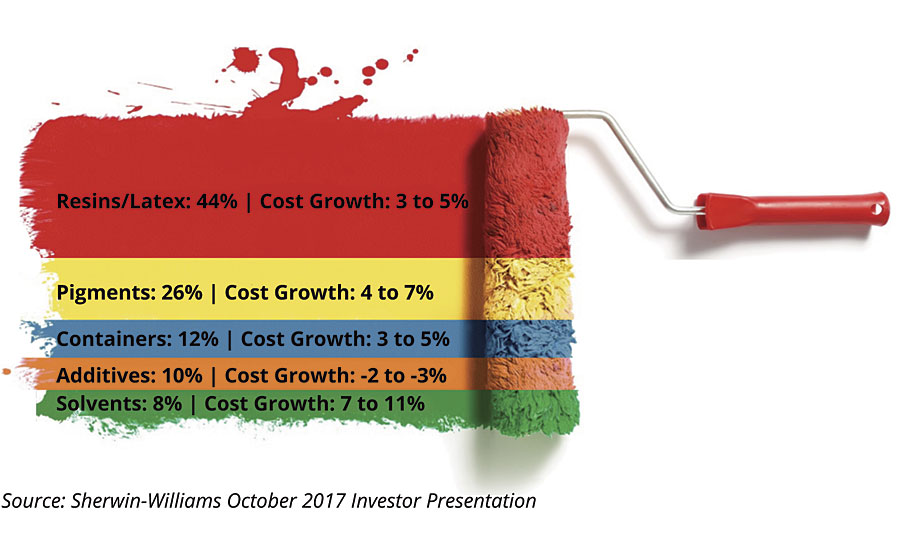

According to estimates from Sherwin-Williams, costs for resins, latex and pigments, (which collectively account for more than half of coatings raw material costs) increased anywhere from 3-7% in 2017, depending on the product. Solvents, which comprise nearly 10% of raw material costs and tend to more closely follow the price of oil, increased an average of 7-11%. In response to rising raw material costs in late 2016 and 2017, both PPG and Sherwin-Williams issued recent price increases ranging from 3-6% across their portfolio, and noted that they would announce further increases if costs continue to rise (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 » Coatings industry product breakdown

In addition to raw materials and procurement, other areas of potential cost savings in coatings acquisitions include manufacturing and production, overhead and other selling, general and administrative (SG&A), and transportation/logistics. SG&A and manufacturing cost synergies are expected to account for more than half of the projected synergies in the Sherwin-Williams/Valspar transaction, and are generally achieved fairly soon after closing.

Not all synergies involve cost reductions, however. As noted above, Sherwin-Williams expects to generate $65 million of annual revenue synergies from Valspar. “Revenue synergy” is the term used to describe a buyer’s ability to increase the revenue velocity of the combined entity following an acquisition. These synergies can occur when two firms combine their R&D/technology capabilities, customer bases and product portfolios to enhance their competitive position in the market. As an example, Sherwin-Williams can now offer its products to the thousands of independent dealers and hardware stores that sell Valspar Paints, and conversely, Sherwin-Williams can consider offering certain Valspar products through its network of more than 4,000 company outlets.

Revenue synergy through shared technology is an aspect of the Nippon Paint/Dunn-Edwards transaction that we think is being underappreciated by the market. Although Nippon Paint did not previously participate in the North American architectural market, it does hold a strong position in the architectural and industrial coatings market in Asia and has a leading global position in automotive coatings. Over time, we believe that Nippon will use Dunn-Edwards as a platform to launch new architectural and light industrial products in the U.S. market, supported by Nippon’s coatings technology and R&D resources. This should allow Dunn-Edwards to enhance its competitive position against other U.S. majors and potentially accelerate its revenue growth.

Our Outlook: Key Changes Ahead?

Despite considering ourselves true industry insiders, with more than 25 years of paint and coating M&A experience, predicting the future is incredibly difficult. As we mentioned above, several of the larger deals that occurred in recent years came as a surprise to most, so trying to anticipate the next major merger or acquisition is challenging at best. Keeping in mind that many significant acquisitions are announced at year end (after we have submitted this article), we’ll make a few observations about key trends we’re seeing in the architectural coatings M&A market, and highlight a few changes that could be coming.

With three companies (Sherwin-Williams (now including Valspar), PPG and Masco/Behr) now controlling more than 70% of the North American architectural coatings market, many wonder whether the end is in sight for independent decorative coatings companies. We don’t think so. Paint contractors tend to be exceptionally loyal, and strong mid-tier companies like Kelly-Moore, Cloverdale, California Products and Diamond-Vogel have generated deep customer loyalty by emphasizing quality and service, and through a decades-long regional focus. We believe mid-sized regional paint companies will continue to exist and even thrive. In fact, consolidation among the majors could present opportunity for smaller, more nimble competitors to take incremental share by focusing on the little things and saying “yes” to every customer need. History tells us that customer service can languish during a major acquisition integration, and strong competitors will position themselves to capitalize if this occurs. However, continued success for smaller formulators will require perfect strategy execution and tight cost management as the majors continue building scale.

We see the major coatings companies continuing their aggressive quest for acquisitions, although a scarcity of architectural coatings targets in North America will lead them to focus more on international markets. Architectural coatings acquisitions in North America are likely to involve smaller bolt-on companies that bring a specific brand or specialty product line. With publicly traded coatings companies trading at or above all-time highs, investors are demanding growth rates that can only be achieved with the help of M&A.

We think competition in the independent dealer and hardware channel will only grow stronger as incumbents continue to battle for share within a modestly contracting segment. We continue to wonder if Benjamin Moore will look to M&A in an attempt to diversify itself from this channel.

Taking a longer-term view, we do believe that the competitive environment for independent/regional paint companies will become more difficult as the majors continue increasing their size, scale and capabilities. Perhaps the Nippon/Dunn-Edwards deal will spur additional M&A activity among mid-tier independents – only time will tell. Regardless, we expect consolidation to remain a key theme in the architectural coatings market for the foreseeable future.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!