Intelligently Selecting Between a Patent and a Trade Secret

Choosing between a patent and a trade secret can be an agonizing decision, particularly in the coatings industry. Often, confirming that the right decision was made is only realized years after the decision, with the benefit of hindsight. The intention of this article is not to persuade a decision maker to file a patent application or to maintain a trade secret. Instead, this article provides a brief overview of patents, trade secrets, and an in-depth discussion of infrequently used procedural options available at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that can be leveraged to gather critical information and thereby enable a decision maker to confidently elect to either apply for a patent or maintain a trade secret.

Most coatings formulators understand that obtaining a patent on a coating formulation is a valuable asset. This is because patents provide the ability to exclude competitors from making, using, offering for sale, selling and importing the claimed formulation. However, the decision to apply for a patent may not be an easy one – as the outcome is not guaranteed. For example, for fiscal year 2019, the USPTO allowed 74% of patent applications. In addition, of the allowed patent applications, the claims of the vast majority of these applications were narrowed during the prosecution before the USPTO. In other words, at the conclusion of the application process before the USPTO, 26% of applicants are left empty handed, and the vast majority of remaining applicants obtained less than what they originally asked for.

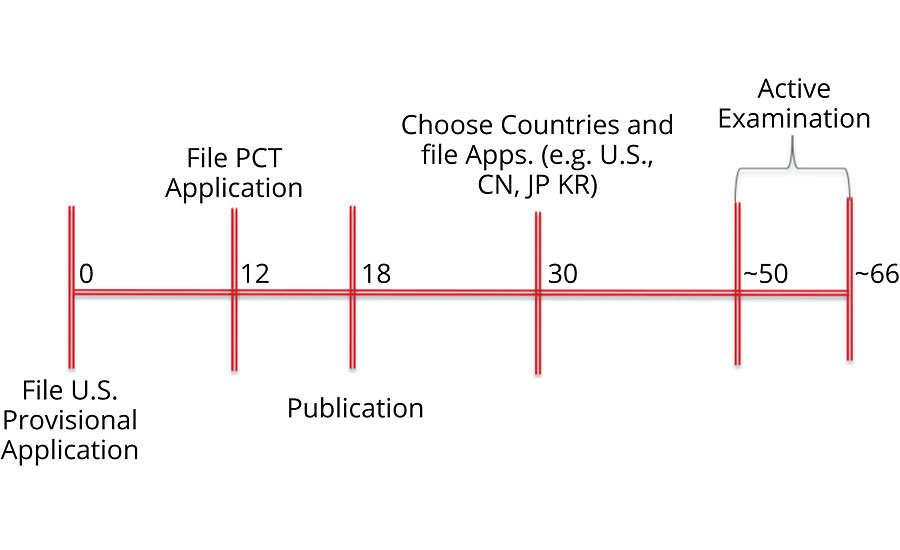

There are many procedural paths to obtaining a granted patent. Generally, these paths fall within two broad categories. The first category relates to applicants focused on protecting their formulation solely in the U.S. In contrast, the second path relates to applicants focused on protecting their formulation in a variety of countries (i.e., a global approach). Figure 1 represents a typical patent application filing strategy for the global approach, which is the most common approach for a globally focused coating company.

Regardless of the particular filing strategy, a clock begins to tick when the first document is filed. Understanding the timing of three events is critical for the purposes of this discussion. First, after the filing of the first document (a U.S. provisional in Fig 1) any subsequent application absolutely must be filed within 12 months from filing of the first document (a patent application filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty, or PCT application in Fig 1). Second, at 18 months from the filing of the first document, the PCT application (global approach) or U.S. non-provisional application (U.S. approach not shown) will publish. Lastly, at some point in time well after the application publishes, the USPTO will begin actively examining the application. These events are significant because, as described further below, by the time the applicant understands the outcome of the patent application process, the applicant has sacrificed their ability to maintain a trade secret due to the publication of the patent application. This can be a harsh result if the applicant’s patent application is denied by the USPTO or if the applicant is dissatisfied with the claim scope ultimately allowed by the USPTO. With the benefit of hindsight with either of these negative outcomes, the applicant would likely have preferred to maintain the formulation as a trade secret.

Referring now to trade secrets, trade secrets may be used to protect coating formulations that are not easily susceptible to reverse engineering. However, it needs to be appreciated that every internally kept secret does not rise to the level of a “trade secret.” Generally, an owner of a secret needs to make “reasonable efforts” to maintain the secret as a trade secret. Examples of such reasonable efforts may include: labeling formulations as “confidential,” restricting access to the confidential formula to essential personnel and ensuring that this select group of individuals understands that the confidential formula is a trade secret. Typically, the owner of a trade secret seeks to maintain a competitive advantage by ensuring that individuals aware of the trade secret are precluded from transferring the information to a competitor (e.g. via job hopping).

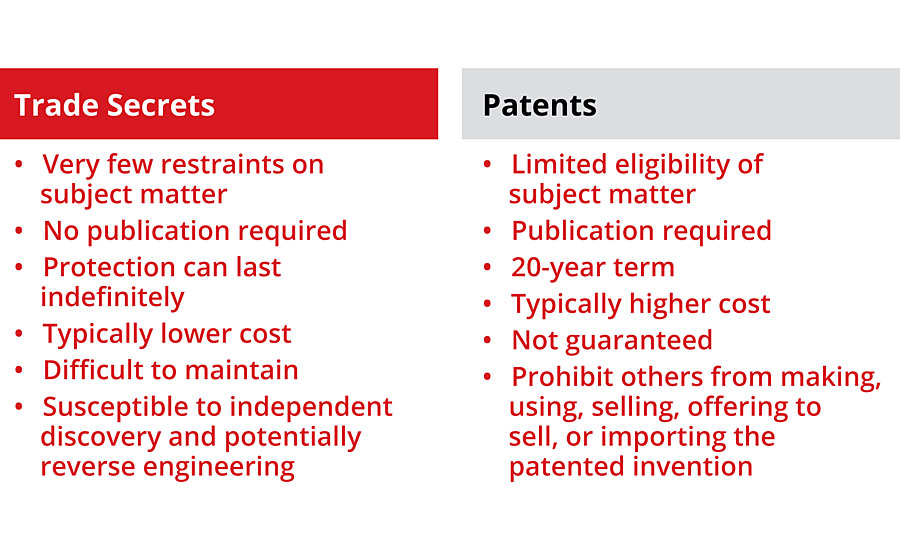

Trade secret protection inherently has certain disadvantages in comparison to patents. Most notably, a trade secret offers no protection against a competitor that independently develops the exact or a similar formulation. In contrast, the objective of a patent is to not just protect the exact formulation but to also protect similar formulations. An additional comparison of patents and trade secrets is provided in Figure 2.

As shown in Fig 2, these two forms of protection have almost nothing in common. Accordingly, a decision maker electing to protect a formulation via a trade secret is forced to (perhaps uncomfortably) rely on the fact that a competitor will not independently replicate the formulation.

As stated in the beginning of this article, selecting between a patent and a trade secret can be an agonizing decision. No one enjoys making a decision without the requisite level of information. However, the decision maker is often forced to elect between a patent application and a trade secret without a firm understanding of the likelihood of success of the application and without a firm understanding of the ultimate claim scope. This decision is further pressured by the worst-case scenario – an unsuccessful patent application that publishes and is subsequently denied by the USPTO, in which the publication of the application prevents the applicant from maintaining the formulation as a trade secret.

So, the question becomes, what can be done to reduce the uncertainty associated with selecting between a patent application and a trade secret. The answer is found in infrequently used procedural mechanisms available at the USPTO.

Procedural Mechanism #1 (U.S. Focus)

The first procedural option relates to coating formulations where patent protection is only desired in the U.S. When filing a U.S. non-provisional patent application, the applicant may file a Non-Publication request at the time of filing. As the name suggests, filing this request will direct the USPTO to not publish the patent application after 18 months of pendency. This request must be made at the time of filing the application. The applicant must also certify that the invention disclosed in the application has not and will not be the subject of an application filed in another country or under a multi-lateral international agreement. Although the application does not publish at the 18 th month date, if the applicant is ultimately successful, the granted patent will publish after the applicant submits an issue fee payment to the USPTO.

The significance of this procedure is that it allows the applicant to file a patent application without ever disclosing the application to the public during the pendency of the application. Hence, the applicant is able to simultaneously maintain the formulation as a trade secret during the pendency of the application. Once a final disposition is reached at the USPTO, the applicant is able to intelligently choose between allowing the patent to grant or maintaining a trade secret. Specifically, the applicant is able to assess whether a patent application will grant and evaluate the scope of the claims, which is exactly the information that a decision maker would prefer to consider when electing between a patent and trade secret. In the event that the decision maker prefers patent protection, the decision maker merely pays the issue fee. On the other hand, if the decision maker prefers the path of trade secret protection after assessing the scope of the monopoly offered by the USPTO, the applicant merely refuses to pay the issue fee, which results in the abandonment of the patent application without any publication.

Procedural Mechanisms #2 and #3 (Global Focus)

Unlike the first procedural option, the second and third options are designed to gather similar information to option 1, but without sacrificing the ability to pursue the subject matter of the application in foreign jurisdictions. Please recall from the above discussion that after a first application is filed, the applicant must file any subsequent applications within 12 months. Thus, under procedural options 2 and 3, the information must be gathered within 12 months of filing the first application. Please also recall that under a typical patent application filing strategy, substantive examination at the USPTO occurs much later than 12 months for the first filing. To this end, the second and third procedural options seek to accelerate the examination at the USPTO.

Procedural Mechanism 2 is officially referred to as “Track 1 Prioritized Examination” by the USPTO. The USPTO’s stated goal of this procedure is to provide a final decision as to the patentability of the application within 12 months. To participate in Track 1 Prioritized Examination, the Applicant is required to file a petition with the USPTO and pay an additional fee to the USPTO of $4,000 (assuming the applicant is classified as a large entity). In other words, the USPTO allows the applicant to pay an additional fee to “cut in line” and begin examination almost immediately. After the USPTO examines the application, an Office Action is issued that addresses the merits of the application. The applicant is required to file an appropriate response to the Office Action within three months to maintain the status as a Track 1 application. Ideally, given the critical objective of obtaining a decision from the USPTO in less than a year to enable the applicant to pursue foreign patent applications, the inventors and the prosecuting attorney would work towards filing a response well before the three-month date.

Typically, a motivated applicant prosecuting a Track 1 application is able to determine whether the USPTO will allow the application and assess the scope of the allowed claims within 12 months. This timing is significant because this critical information is collected before the publication of the U.S. application and also before the 12 month date to file the application in foreign jurisdictions. Accordingly, because this information is gathered in secrecy, the applicant’s ability to maintain the formulation as a trade secret is preserved in the event that the applicant is dissatisfied with the outcome and elects to abandon the application.

As an additional benefit of this strategy, unrelated to gathering information to enable an intelligent selection between a patent application and a trade secret, the success before the USPTO can be leveraged in most foreign jurisdictions if the claim scope of the patent applications filed in these foreign jurisdictions is identical to the granted U.S. patent and the applicant files a “Patent Prosecution Highway” (PPH) request. This request accelerates the examination in the foreign jurisdictions and typically results in a smoother application process, which may ultimately assist in offsetting the additional $4,000 fee to request Track 1 Prioritized Examination for the initial U.S. application.

Procedural Mechanism 3 is officially referred to as “Accelerated Examination” by the USPTO. Accelerated Examination and Track I Prioritized Examination are very similar prosecution strategies, with each pathway sharing the goal of achieving a final determination as to the patentability of the application within 12 months. Accelerated Examination, unlike Track 1 Prioritized Examination, requires the applicant to submit a detailed pre-examination report that includes a detailed search methodology, a list of the relevant references, and an explanation as to how each claim is patentable over the list of references. Said differently, Accelerated Examination requires the applicant to prepare a pre-examination report that is akin to the work product that the USPTO would prepare in a first Office Action with the added explanation of patentability requirement. In exchange for the added burden of preparing the pre-examination search report, the fee for requesting Accelerated Examination is merely $140. However, the cost benefit of Accelerated Examination, in comparison to Track I Prioritized Examination, is largely eroded by the legal fees to prepare the pre-examination search report.

Conclusion

In summary, a variety of procedural mechanisms are available at the USPTO that can be leveraged to gather critical information concerning whether the application will ultimately grant as a patent and the scope of the resulting claims. Although this information comes at an increased cost, it enables the decision maker to truly make an informed decision when choosing between patent and trade secret protection

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!