Answer to Lindsey’s Volatile Recommendation

Editor’s note: Following is Keith Moody’s answer to the conundrum presented in “Lindsey’s Volatile Recommendation” in the June 2020 issue of PCI.

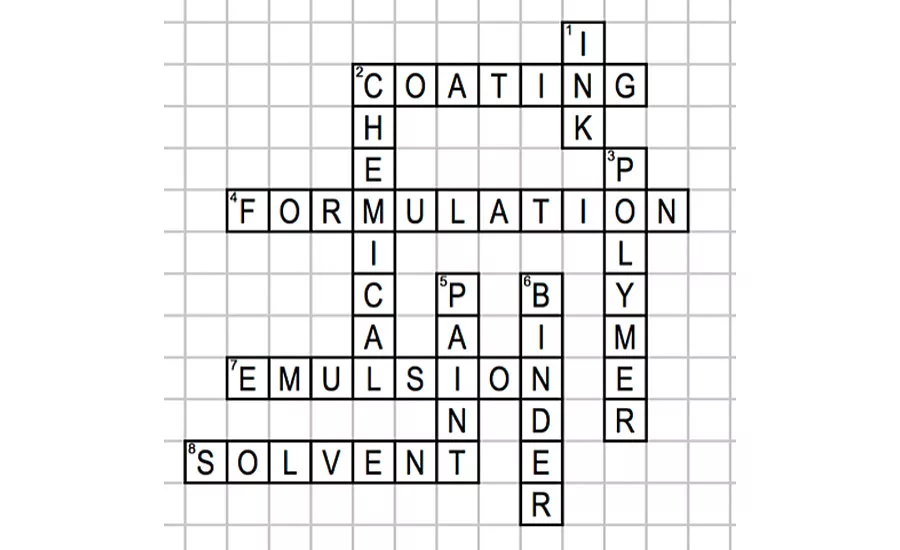

Lindsey Doyle had made a recommendation to one of Dr. E. Coates’ senior scientists about a solvent change in their electrocoat formulation. The formulation used a small amount of an ester alcohol solvent, and the scientist had asked if Lindsey could recommend a less volatile solvent to reduce the VOC of the e-coat. Lindsey recommended replacing the ester alcohol with a similar diester solvent with a lower relative evaporation rate. Dr. Coates was upset that Lindsey’s recommended change in the formulation caused their customers’ e-coat tank to be out of specification for percent solids. What had been wrong with Lindsey’s recommendation?

The volatility of a solvent should never be confused with the amount of volatile organic compounds (VOC) in a formulation. While the volatility of a solvent is usually indicated by relative evaporation rate (RER) of a solvent, the VOC content is the measured amount of a specific material in a paint formulation.

In the US, the EPA defines VOC as any compound of carbon that participates in atmospheric photochemical reactions. Since almost all solvents, except a very few, participate in these reactions that lead to formation of ground-level ozone or smog, almost all solvents are considered VOCs if they are emitted into the atmosphere. Emissions from coatings are based on the total system formulation under specific test conditions. There are several different ways that VOCs are measured, but the most common and most often used by electrocoat manufacturers is the EPA Federal Reference Method 24. This involves heating the coating in a small pan to 110 °C for one hour (ASTM Method 2369) and measuring by weight percent what is lost. The material not lost to the atmosphere and left in the pan is referred to as weight percent nonvolatiles or solids.

The senior scientist was mistaken in assuming that because she replaced an ester alcohol solvent with a less-volatile diester solvent, that the VOCs would be less. In this case both the ester alcohol and the diester solvent are VOCs because they both came out of the e-coat formulation when the customer ran their test for weight percent solids.

When Lindsey got back to the office of Big Time Paint, she ran into Al Kidd and explained what had happened: “I get blamed by Dr. E. Coates, when his scientist should have done a solids check before replacing the ester alcohol solvent with the diester solvent. She should have made sure that the new solvent didn’t come out of the film and not count as VOC before sending the formulation to their customer.”

Al let Lindsey finish her tirade, then spoke directly. “Lindsey, you need to be more careful about your solvent recommendations. While I disagree with Dr. Coates that you are totally to blame, you do share some of the blame for this foul-up. You based your solvent change recommendation on only one property, RER. The customer’s simple question was much more complicated than you realized.”

“Remember, Lindsey, relative evaporation rate is important, but there are many factors that can influence whether a solvent evaporates from a film. RER is measured on pure solvents and doesn’t take into consideration the interaction of the solvent with other ingredients in the coating formulation. Solvent has to diffuse out of a polymer matrix before it can evaporate, and there are many properties of the solvent that can affect this diffusion rate. Solvent properties like molecular composition, molecular weight, branched or linear structure, and solvent type all can have consequences for solvent diffusion from the polymer.”

“For example, the solvent can have attractive or repulsive interactions with the polymers that affect how much solvent is retained in the polymer matrix and how fast the solvent evaporates. You recommended a diester to replace an ester alcohol. The polymers used in e-coat formulations typically contain neutralized acid or amine functional groups and are very polar. These polar polymers can have greater attraction to polar alcoholic solvents. These attractive interactions between the polymer and the solvent are sometimes decreased when changing to a diester solvent. The diester solvent may have less attractive forces for the polymer film, and the solvent requires less energy to escape from the film.”

Al went on to explain, “In an e-coat formulation, the interactions that the solvent has with water can also affect whether the solvent escapes. Alcohol-containing solvents have more hydrogen bonding with water and thus the attractive forces are higher and the solvent has a lower escaping tendency. Hydrogen bonding is why water has a low evaporation rate for such a low-molecular-weight molecule. It is also the reason that low-molecular-weight alcohols, like methanol and ethanol, have much lower relative evaporation rates than their higher-molecular-weight esters, methyl acetate, and ethyl acetate.”

Al added, “Don’t blame the senior scientist when it was your recommendation to make the solvent change. Even though the solvent amount is very low in the total e-coat, the amount of solvent per resin solids is often high. The solvent can have a big effect on the properties of the e-coat. Solvent changes can affect rupture voltage, coulombic efficiency and throwing power. The senior scientist was busy checking all these properties, as well as e-coat bath stability, and trusted that your recommendation of the solvent giving lower VOC was accurate.”

Al then said in a quiet, comforting voice, “Lindsey, remember that VOC can stand for more than one thing. The next time you need to listen to what the customer is really asking and think twice about your recommendation. A good technical representative concentrates as much on the Voice of the Customer (VOC) as the Volatile Organic Content (VOC).”

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!