Scientists Uncover Formula to Predict Cracks in Clay

Researchers have accurately predicted the exact time of the first crack’s emergence in aged clay. Their findings also apply to other forms of drying colloidal layers, such as blood and paint—insights that could aid in disease diagnosis, forensics, painting restoration and improving the quality of paints used for coatings.

Clay, the primary component of natural soils, is used as a modifier in formulating paints and coatings. When subjected to desiccation, colloidal clay suspensions and clayey soils crack due to the accumulation of drying-induced stresses. Even when desiccation is suppressed, aqueous clay suspensions exhibit physical aging, with their elasticity and viscosity evolving continuously over time as the clay particles self-assemble into gel-like networks due to time-dependent inter-particle screened electrostatic interactions.

Researchers studying material science at the Raman Research Institute (RRI), an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology, have proposed a relationship between the time of the first crack’s emergence, fracture energy (the sum of plastic dissipation and stored surface energy) and the elasticity of the drying clay sample, which can help predict the first crack.

Using the theory of linear poroelasticity, they estimated the stress at the surface of the drying sample at the time of crack onset. Linear poroelasticity is a theory for porous media flow that describes the diffusion of water (or any mobile species) in the pores of a saturated elastic gel. They equated this stress with a critical stress predicted by a criterion that states that a crack will grow when the energy released during propagation is equal to or greater than the energy required to create a new crack surface (Griffith’s criterion).

The relationship was validated through a series of experiments. Researchers also found that the same scaling relation applied to other colloidal materials, such as silica gels. The study was published in Physics of Fluids.

“This correlation can be useful while optimizing material design during product development. We can apply this knowledge and suggest adjustments to the material composition during the manufacturing of industry-grade paints and coatings so that the final product is more crack-resistant and of higher quality,” said Dr. Ranjini Bandyopadhyay, professor at RRI and a co-author of the study.

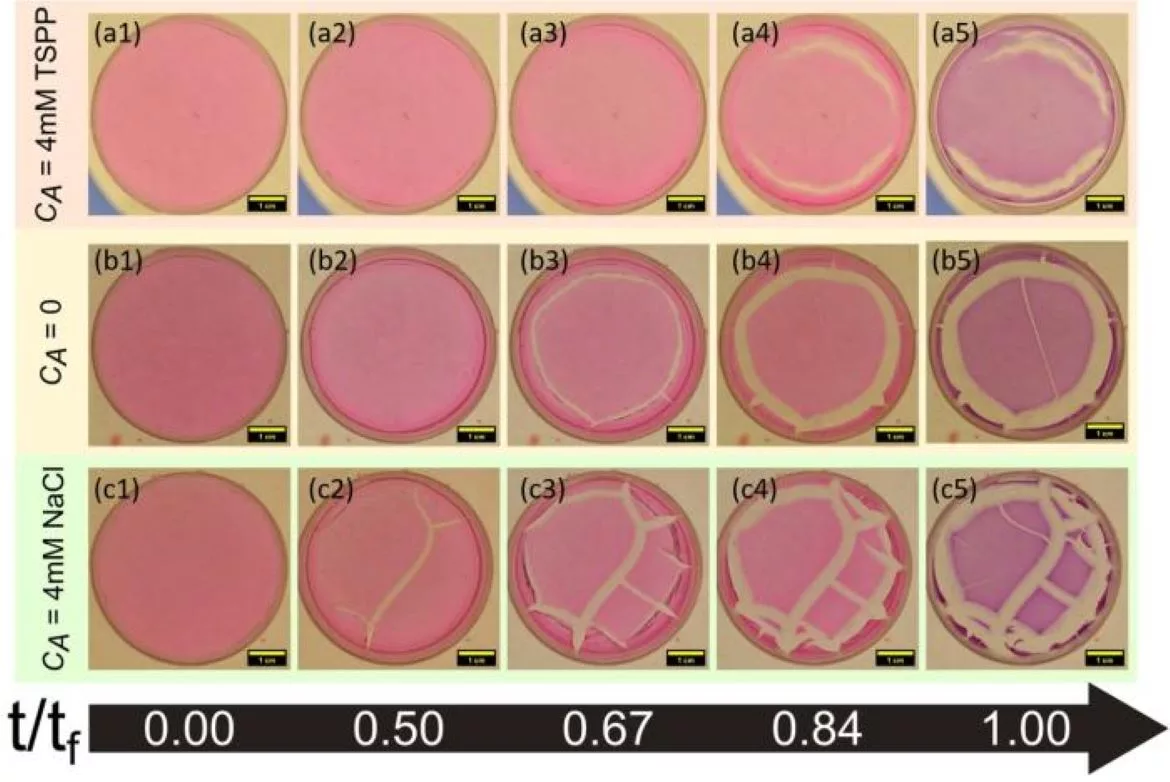

Using Laponite, a synthetic clay with disk-shaped particles sized 25-30 nanometers and one nanometer in thickness, the team created multiple Laponite samples with increasing elasticities. Each sample was dried at temperatures ranging from 35 to 50 degrees Celsius in a petri dish. The samples took between 18 and 24 hours to dry completely, and the rate of evaporation and elasticity were measured for each sample. As water evaporated from the Laponite samples, the particles rearranged and stresses developed on the surface of the material.

Higher sample elasticity indicates a better ability of the sample to deform under the influence of these stresses.

“The first crack emerged somewhere between 10 and 14 hours. Depending on the sample’s elasticity and fracture energy, the emergence time of the cracks varied. The crack onset time decreases with increasing temperature due to faster solvent loss and, therefore, a more rapid enhancement in clay elasticity. The sample dries faster at higher temperatures, enhancing the rate of stress development on its surface. Clay particles and their interactions influence the crack onset time because they govern the sample solidification rate and, therefore, mechanical properties such as fracture energy and elasticity,” said Vaibhav Parmar, the first author of the paper and a Ph.D. student at RRI.

It was also noted that the cracks started developing first at the outer walls of the petri dish and later progressed inward. Later, networks of cracks developed as the sample aged.

The researchers stated that crack formation in clay is a complex phenomenon observed over a range of length scales, highlighting the need to understand drying-induced cracks. This information could help improve the understanding of geophysical and mechanical processes.

Clay is a highly heat-resistant material and an excellent insulator, making it the preferred choice for extreme heat environment applications, such as spacecraft coatings. Researchers further noted that a clay-water mixture initially behaves like a flowing liquid but, over time, can turn into a viscoelastic solid, exhibiting properties of both liquid and solid. This study is significant as it observed the effect of physical aging on the desiccation of clay.

“We concluded that the more elastic the material, the lower its fracture energy and the faster the cracks developed. We have suggested a recipe for predicting crack formation in terms of the sample elasticity and fracture energy, which can be measured in laboratory experiments. Relationships can also be developed for cyclic temperature changes to mimic diurnal temperature fluctuations,” Bandyopadhyay said.

The research shows that by varying the concentration of the material, the salt, or the pH levels, it is possible to tune the material’s elasticity and, in turn, its cracking onset. This could be used to delay cracks in coatings on a spacecraft or on a medicine capsule, which are produced in a controlled environment.

This article was originally published by the Raman Research Institute and can be viewed here.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!