A Novel Mixed Mineral Thixotrope Technology for Industrial Coatings

As regulations call for lower VOC levels, it becomes increasingly difficult to design coatings with appropriate rheology. Properties such as sag resistance and settling resistance become more difficult to balance with package viscosity. The use of Garamite® mixed mineral thixotropes (MMTs) can help with key properties such as sag resistance and settling resistance while maintaining a reasonable package viscosity.

This article explains how and why Garamite works. MMTs are compared to various thixotrope technologies used in different types of industrial coatings, including high-solids epoxies, low-HAPs systems, high-solids alkyds, chain-stopped alkyds and zinc primers. Also discussed are methods of incorporation and other processing considerations.

Mixed Mineral Thixotropes

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products

|

| Table 1 Click to enlarge |

MMTs are a combination of two different morphologies; one being a plate, the other being a rod. They are off-white powders that are organically modified and have a specific gravity of about 1.6. If needed for very thin-film applications, there is a micronized version available [Garamite 2578 (8 µm d50 grain size)]. However, the primary product is Garamite 1958 (32 µm d50 grain size) for most applications (Table 1).

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products

|

| Figure 1 Click to enlarge |

How MMTs Work

MMTs thicken systems similarly to the way in which organoclays work, using hydrogen bonding to form a three-dimensional network (Figure 1). However, MMT networks use different spacing than do traditional organoclays, due to the different particle shapes involved.

Garamite Compared to Organoclay

There are a variety of organoclays, but for the purpose of this article we will stick to the basics and compare and contrast activated versus self-activating organoclays. A simple way to look at organoclay is to look at the level and type of quaternary amine modification on the clay. The lowest levels, considered to be traditional organoclays, have to be activated with some type of polar activator. These organoclays usually are more efficient for thickening, but can be more difficult to incorporate, and order of addition can be more critical. Self-activating organoclays tend to have a higher loading of quaternary amine on them. This higher level of quaternary amine typically makes them easier to incorporate, but slightly less efficient than traditional organoclays, all other things being equal.

Also the type of quaternary amine modification determines which type of solvent system the organoclay will work best in. Certain quaternary amines work better in aliphatic vs. aromatic systems, for example.

Organoclays are typically made from smectite and come in a form somewhat like a deck of cards, with clay particles stacked one upon another. As organoclay manufacturers we impart a lot of energy to break this naturally occurring layered mineral apart. But in the end, Mother Nature tries to return the clay back to its natural state. Including the other mineral type helps to prevent this from occurring.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 2 Click to enlarge |

Garamite 1958 has a unique morphology of rods and plates as compared to conventional organoclays that use just a plate-like layered structure (Figure 2). This morphology plays a role in not only the ease of incorporation, but also in the efficacy of sag resistance and settling resistance over heat aging.

MMT Advantages

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 3 Click to enlarge |

In practical terms we have found that Garamite tends to build less package viscosity while providing more sag resistance than organoclays. The MMTs provide 50% or more increase in sag resistance at equal use levels versus organoclays. Not only is sag resistance increased, but runs are reduced or eliminated (Figure 3). This becomes more important as VOC goes down and solids go up. The trend for higher-solids coatings is to have excessive package viscosity without sufficient sag resistance.

We also found that the quaternary amine does not play as important a role in determining efficiency in a specific solvent system, like with traditional organoclays. In recent studies we have seen the Garamite 1958 work across a very wide range of solvent systems. Does this mean it will work every time? Probably not. But it does mean MMTs are more flexible as compared to organoclays and have the ability to work in more systems. This flexibility could reduce the number of thixotropes needed.

The morphology also plays a role in ease of incorporation. Unlike organoclays, Garamite is easily incorporated into the coating formulation without using a high level of quaternary amine. In part, we believe this has to do with the difference in having a combination of rods and plates and having more spacing, making it much more difficult for Mother Nature to put the clay back to its natural state.

Another advantage of the MMTs is that in most systems polar activators are not necessary. If needed to gain a little more efficiency, one can use polar activators in a manner similar to traditional organoclays.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 4 Click to enlarge |

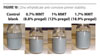

Another key advantage to the coatings manufacturer is the ability to make high-solids premixes at pourable viscosities. Garamite 1958 can be used to make a pourable pregel as high as 20% solids. Typical pregels made from traditional organoclays are usually not pourable once they reach about 4 or 5% solids. Having the ability to make pourable high-solids pregels makes it easier to formulate in systems where one has low levels of solvents (Figure 4).

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 5 Click to enlarge |

When comparing MMTs to fumed silica, the big difference is in bulk densities. While the MMTs have a low bulk density compared to traditional organoclays, it is much higher than fumed silica, which has an extremely low bulk density. This leads to issues with dusting and incorporation for the fumed silica as compared to Garamite (Figure 5).

When replacing fumed silica with Garamite, one can typically reduce the level of thixotrope by 40% or more to get equal sag resistance and eliminate runs. One advantage for fumed silica is clarity in the final film. However, this property is not noticed in filled systems. Also, it bears mentioning that some color is imparted into clear, unfilled systems by the MMT. In unfilled systems, another shortcoming would be that the MMTs do not perform quite as well for sag resistance. It is as though the MMT needs to space something to work.

When comparing Garamite to polyamides or castor derivatives, the MMT is much less sensitive to processing conditions. The comparison thixotropes need to achieve the correct temperature and dwell time to be activated and work properly, while Garamite does not. They also require the proper agitation during cooling in order to prevent the system from forming a false body. This can make the other thixotropes much more difficult to deal with in the long run. Also, it may be possible to use these products during manufacture without the ideal conditions, yet still pass QC. Then somewhere down the road the system may have seeding problems or lose stability. Stability can be lost in different areas, whether it be sag resistance falling off or package viscosity rising substantially. While polyamides in particular may be among the best at yielding that perfect buttery feel, they are much less forgiving during manufacture than MMTs.

Comparisons in Various Systems

High-Solids Epoxy

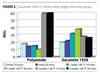

In the first system, we compared Garamite 1958 to a polyamide in a 100% solids, edge-retentive epoxy. This system was based on Epon 862, and the hardener was Cardolite’s NX-5079 (phenalkamine). The starting-point formula had 1% polyamide in Part A and 0.59% in Part B. Originally we used the Garamite 1958 only in Part A. While the efficiency was there we discovered that the sag resistance fell off during the pot life. We then realized that by splitting the Garamite 1958 50:50 in both Part A and Part B that not only did the coating have a reasonable sag resistance over the pot life, but that it was more stable during the shelf life during heat aging.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 6 Click to enlarge |

Due to the lower viscosity of the phenalkamine, a 20% high-solids pregel was made in the phenalkamine, which was pourable, then added to the rest of the Cardolite NX-5079.

As Figure 6 shows, Garamite 1958 is both efficient and stable. The table shows the pot life stability at 10 minutes and at 30 minutes, as well as heat age stability over a month at 140 °F. It also points to a stability issue for the polyamide, which dictates the end user would probably add solvent to cut viscosity, while that shouldn’t be necessary for the epoxy made with the Garamite 1958.

Epoxy Floor Coating

Figure 7 highlights the suspension of quartz sand in an epoxy floor coating. Garamite 1958 outperforms fumed silica and significantly outperforms conventional organoclay. Notice the phase separation of the modification made with organoclay. This is also the first time in this article we use a rheological enhancer, the BYK R605. This class of material is used from time to time to boost or enhance the properties of the thixotrope.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 7 Click to enlarge |

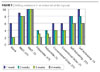

Low-HAPs Primer

The next study was of a low-HAPs primer based on a chain-stopped short oil alkyd. In this study we compared the MMT to a polyamide, both conventional and self-activating organoclays, as well as a blank. Even though the polyamide yielded the highest viscosity, the Garamite at the lowest level, 2 pounds per 100 gallons, had a settling resistance that matched the higher loading level of polyamide (Figure 8). This allows for lower package viscosity, lower cost and increased ease of manufacture.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 8 Click to enlarge |

Industrial White Topcoat

The next study looked at an industrial white topcoat. As with the previous study, we compared the MMT to a polyamide, conventional and self-activating organoclays, and a blank. In this case the polyamide had the highest viscosity but did not do well for the prevention of settling during heat aging (Figure 9). This system turned out to be a little more difficult than the previous system, as it took the higher (4 pounds per 100 gallon) level of Garamite to eliminate the settling.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 9 Click to enlarge |

Zinc Primer

The next study intended to find the level of Garamite needed to suspend zinc through the use of high-solids pregels. To totally suspend the zinc it took 1.7% of the Garamite 1958 that was done in a very high solids pregel of 18.9%. This pregel was both pourable and pumpable (Figure 10).

Polyurethane Systems

Other potential applications include polyurethanes, epoxy adhesives and grouts, unsaturated polyesters, metallic coatings and aerosol coatings.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 10 Click to enlarge |

For polyurethanes, in particular the moisture-cured systems, it should be noted that Garamite contains 4% water. The water is adhering to the clay surface and is not automatically available for reaction with the isocyanate. But for reactivity and storage stability it should be tested to see if the water in Garamite causes issues in these water-sensitive formulations. To overcome this, Garamite could be oven dried at 120 °C to lower the moisture content, or the use of moisture scavengers could be employed.

Figure 11 evaluates the effectiveness of Garamite compared to organoclay in a PU system.

Courtesy of Southern Clay Products Courtesy of Southern Clay Products |

| Figure 11 Click to enlarge |

How to Use Garamite

The use of Garamite is very similar to organoclays. In solvent-containing systems that can tolerate such processing, always add the Garamite to the solvent. The Garamite should be added at a percentage high enough to make a pregel that is still pourable. While not completely necessary, this will consistently yield the most efficient results. If solvent is not available, then add the Garamite to a reactive diluent or to the lowest-viscosity resin, with the first choice being the diluent. As you move from solvent to diluent to resin the efficiency will drop somewhat. However, the Garamite will still in most cases maintain an advantage over other competitive materials.

Cowles-type shear will suffice in all applications for dispersing the MMTs. Other incorporation methods can also be used.

We will now recommend some starting use levels, keeping in mind that we are talking in generalities, and some systems have different demands than expected. When compared to fumed silica, a good starting point is at about 60% of the level of fumed silica used. Keep in mind that the viscosity may be lower, but the sag resistance should be greater. When replacing organoclay, start the bottom of your ladder study at 50% and work up. The 50% level is also a good place to start the replacement of either the polyamides or the castor derivatives. Always be mindful of the fact the actual rheology of the finished system may not match exactly. It is not unusual for the package viscosity to be lower and the sag resistance to be higher.

When working with epoxies do not be afraid to try various combinations between Part A and Part B. In 100% solids epoxies, dispersing the Garamite directly into the epoxy itself or the hardener is fine. Be sure to test for compatibility and stability. Placement can be important to both pot life and shelf life and should be tested.

Conclusions

As coating formulations move to lower VOCs and higher solids, the demand on the thixotrope becomes more difficult as it pertains to package viscosity, sag and settling resistance. The package viscosity tends to go higher and the sag and settling resistance trend lower, making it difficult for the end user to provide a uniform surface to protect the substrate. We have shown that Garamite 1958 fills this need in many cases as compared to conventional organoclays, polyamides and fumed silicas. Garamite 1958 has a unique morphology of rods and plates as compared to conventional organoclays that use just a plate-like layered structure.

This morphology plays a role in not only the ease of incorporation, but also in the efficacy of sag resistance and settling resistance over heat aging. Garamite is significantly easier to incorporate when compared to polyamides and castor derivatives and does not have their temperature and dwell time limitations. Garamite provides the sag resistance and settling resistance at much lower use levels, as much as 60% lower, than these other thixotropes.

For more information, visit www.scprod.com.

This paper was presented at the 2010 Coatings Trends and Technologies Conference, sponsored by the Chicago Society for Coatings Technology and PCI Magazine, in Lombard, IL.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!