A Work in Progress

The company continually monitors consumer demand and industry trends and makes minor finishing-line improvements that allow it to meet those demands with quality products as fast as, or faster than, anyone else. Ultracraft seems to have a new project, or what Waite calls a "restructuring," in the works every year or two. Completing smaller projects more often, rather than less-frequent major projects, has helped the company remain lean and flexible in its marketplace while keeping cash outlays to a minimum.

In its latest completed project (the company has recently started a new one), Ultracraft has increased its line speed from 12 to 14 fpm to 18 to 20 fpm, increased productivity, increased the number of cabinet components finished from about 800 pieces per eight-hour shift to 1,500 pieces, and has added new customer options, all without adding floor space or more employees. Part of the driving force behind that restructuring, which was completed last spring, was a 50% increase in customer orders in 2003 over 2002.

"It's up more than that for the first three months of 2004," Waite says proudly.

Besides the dramatic increase in orders and constraints on capacity, Ultracraft also noticed that its product mix had significantly changed. Ultracraft primarily builds kitchen and bathroom cabinets for what Waite calls the "high end of the broadly defined middle market," a group of consumers with high expectations, frequently changing tastes and an appetite for numerous options. Ultracraft now offers 172 different product/finish combinations and will customize any of its product offerings. Ultracraft also offers products in thermofoil, melamine, laminate and eurotek veneer, which is prefinished upon arrival.

"I've known Pete Sink [Pneu-Mech's sales engineer] for 18 years, and we've done a variety of projects together over that time," Waite says. Sink is a part of the team approach Waite uses when a new project is started. Besides Sink and Waite, the team also includes members of the finishing, maintenance and production departments. "We brainstorm about the objectives, the scope we're trying to accomplish, and at the end of the day we create a new line."

With each new project, Waite reminds Sink and Pneu-Mech of one of the main ongoing ground rules: "I gotta remodel the kitchen, but I can't miss a meal," he says. "We can't miss customer orders." During working hours, Pneu-Mech needed to find ways to do its work without disturbing production. Any work that would halt production needed to be done after working hours and on weekends.

From the top

Ultracraft finishes solid wood and wood with a veneer surface. The cabinet parts begin their journey through the plant in a sanding room next to the finishing department. Pieces are progressively sanded by both manual and automatic sanding equipment. At manual tables, employees use orbital and jitterbug sanders and other hand-held equipment. There are also wide-belt sanders and dual-process equipment that can automatically switch from 150 to 180 grit, depending on the parts' requirements. Parts generally are manually sanded at the profiles and edges, where the automatic sanders have difficulty performing.Parts are then hung on the finishing line from hooks where holes have been bored for hinges or drawer heads, or in a location that won't be seen. Parts travel by overhead conveyer to the staining area, where various staining applications and techniques employ no-wipe and wiping stains and enamels. These parts had been manually moved by buggy from the sanding operation to staining until a few years ago, when another project with Pneu-Mech connected the two operations to improve productivity.

In the staining area, there are three operators in three opposing booths so that a stain is applied to one side in one booth and then moves to the next booth for finishing on the opposite side. The third booth is used on parts that require an additional coat on the front. The applicators in each section of the finishing department use air-assisted airless spray guns from DeVilbiss (Glendale Heights, IL), which are purchased locally through Air Power. There are also stain wipers on the line to ensure proper staining in the profiles and proper depth and quality standards for particular stains and species of wood.

Unlike other industries, operators may need to change colors every few minutes. "None of this is done in a batch," Waite says. "It's all just-in-time. You may have one color coming down and another right after that, one antique and the next not, one glazed and the next not." There's a different pot and gun for each type of stain and glaze.

The line then proceeds through a series of loops to a convection drying oven, through which the parts pass for a couple of minutes in temperatures ranging from 130 to 150ºF. Most of the drying occurs at ambient temperature while the parts move toward the oven.

The next stage is a sealant booth where a catalyzed conversion varnish clearcoat, rather than a lacquer, is applied in opposing booths.

After the sealer is applied, products travel to a 90-foot-long convection oven. Before the line speeds were increased last spring, the products used to take about eight minutes to travel the length of the oven, which reaches about 150ºF toward the end. That time has been cut by about a third.

Parts spend about the same amount of time on the line as in the oven. The length of the line was significantly increased in last spring's project to give pieces more flash-off time and ensure the coatings are hard and ready for sanding.

Sustaining or improving the quality of the finish-its hardness, consistency and sheen-is the first consideration when a new project is contemplated. "This is critical," Waite says. "Our customers' expectations are very high these days."

After exiting the oven, the line makes a 90-degree turn toward the sealant sanders. Sealer sanding is done by hand on the fly while the parts are hanging to ensure parts are smooth to the touch before the final topcoat.

Parts travel to another work station where, depending on the product, they could have a conversion varnish glaze applied. This is typically a color different from the basecoat; it's wiped off the flat surfaces, allowing hang-up in the profiles to create a unique look. Here, again, wipers are available to ensure the glaze is properly and evenly applied.

Parts then move toward opposing topcoat booths were they receive the final conversion varnish topcoat of about three wet mils. This is followed by a 10-minute flash-off period on the expanded line.

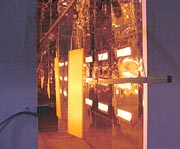

After flash-off, parts enter the new halogen drying oven installed as part of the package last spring. Ultracraft is one of the few companies using the technology, Waite says. Products spend about three minutes in the L-shaped oven, which has three zones and is about 50 feet long and eight feet high.

The rectangular lamps are strategically placed on panels in the oven to provide a burst of heat as parts enter the oven, more intense heat in the middle of the oven, and another burst of heat as parts exit. "The goal is that, as you're leaving the oven, you want to try to carry the heat with the part for an additional few minutes as it goes up the incline and out into the main assembly area," Waite says.

"The new equipment allowed us to minimize our capital expenditure and not have to add space," Waite says. "But that's always the goal-to do more in the space we have-regardless of whether that means moving the line higher or bringing in new technology or bringing in more spray power."

The halogen oven replaced a convection oven. "We made the topcoat oven the sealer oven and the sealer oven became the stain oven," Waite says. "And instead of having a stain oven, we are drying the stain using ambient air."

The new configuration also allowed Ultracraft to "add more heat and more air movement," Waite says. "That was the key to improving our stain process."

"But we reconfigured the whole line," Waite adds. About 900 feet of different loops and angles were added to the line in the finishing department. More than 1,200 additional feet were added to the line to automatically take parts to the assembly portion of the facility. Getting those parts more quickly and efficiently to the "point of use was key," Waite says.

Good fortune, necessary efforts

The period between the beginning of discussions and final startup required about three months; the actual work took place at various times over a three-week period. Startup went without a hitch."It blew our minds," Waite says. "For the first three or four weeks, we really didn't have any glitches at all. It was an immediate, overnight improvement. About a month into the process, we had some minor glitches with the drying times that had to be worked out."

Ultracraft was additionally fortunate because it didn't have to modify any of its coating formulations. The company's coating supplier, Lilly (Highpoint, NC), was part of the initial project team and assured Ultracraft that the coatings would work with the plan as specified.

The domestic manufacturing base in cabinetry hasn't been hard hit-in fact, it's growing, Waite says-unlike the domestic furniture industry. "I see furniture plants closing all around me," he says. The cabinet industry's success is partly because of strong growth in the new-homes market; but a big part, too, is Americans' love of remodeling. Still, the industry, and Ultracraft, need to continually change to keep pace with a continually changing environment.

"The market demands far more choices," Waite says. "We didn't start out with 172 different combinations of products." Ultracraft continues to add more choices in glazing, antiquing and other options.

That's why Ultracraft's line needs to be as flexible as it is fast. "We stay competitive in our niche because of our incredibly short lead times-from two to five weeks to the end-user," Waite says. "That's becoming more common, though it can take up to 12 weeks for other manufacturers. We've learned how to do a batch of one-that's the key-and do it cost-effectively."

"Probably our biggest competitive advantage in our niche is our ability to customize our products," Waite says. "We can do any size in any available product. Overseas, they've become cost-effective at doing high quantities at high speeds and with longer lead times."

In addition to the demand for different styles and colors of cabinets, consumers are asking for more functional cabinets. "Everyone always thought a cabinet is a box is a box is a box," Waite says. But people want them for different rooms, and they want them to provide more service.

"People talk about thinking outside the box," Waite says. "We started thinking inside the box." As a result, Ultracraft's cabinets offer storage systems, pop-up hardware that allows appliances to be pulled down to countertop level, divider trays and other conveniences-at a price.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!