Tailored Emulsifier Portfolios for Sustainable Waterborne Alkyds

No One-Size-Fits-All

The transition toward more sustainable coating technologies has accelerated in response to increasingly stringent VOC regulations and increased market demand for biobased materials. Within the resin design context, waterborne alkyds address sustainability through their high renewable content, derived directly from the oil modifiers, and the availability of low-VOC formulation strategies. Among these, external emulsification with surfactants is particularly versatile since it requires no chemical modification of the alkyd backbone and applies seamlessly across a wide range of alkyd architectures, from short-oil to very long-oil systems.

The most industrially applicable methodology for external emulsification is the catastrophic phase inversion (CPI), where water is gradually introduced into an alkyd–surfactant system under controlled shear, triggering a phase transition from water-in-oil (W/O) to oil-in-water (O/W). The success of CPI depends on a complex interplay of physical parameters (temperature, shear, water addition rate, vessel or agitator geometry) and chemical parameters (emulsifier ionic strength or hydrophilicity, alkyd polarity, neutralization parameters).

When these interdependent parameters are not selectively tailored to a given alkyd–emulsifier system, it often leads to emulsification failures, poor emulsion stability and inferior coating performance, thereby reinforcing the notion that external alkyd emulsification with surfactants is ineffective. To date, no study has systematically isolated the individual role of these variables or investigated their synergistic effects.

We evaluated a six-member Neptem™ emulsifier portfolio, comprising anionic and nonionic grades, fossil-derived and renewable-origin, across more than 30 industrial alkyds (short- to long-oil) to establish compatibility with varying alkyd structures. From that broad screening, seven medium-to-long-oil resins were selected to be presented herein for five focused studies: (1) the impact of mixing hydrodynamics, emulsification temperature and neutralization parameters on CPI performance; (2) benchmarking the biobased emulsifier, grade 21, against fossil-derived and benchmark alkyd surfactants at 6% and 8% loadings; (3) resin-specific emulsifier compatibility under constant CPI conditions; (4) impact of alkyd, emulsifier type or level and emulsification conditions on clear coat performance; (5) impact of emulsifier selection on paint performance.

Materials and Methods

Alkyd 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 are all medium-oil (MO) and long-oil (LO) resins with ≈100% solids and oil lengths in the 55–85% range, but they differ in functionality and molecular architecture (Table 1).

The emulsifier portfolio consists of three anionic surfactants (emulsifier 11, emulsifier 12 RDP, emulsifier 21) and three nonionic EO/PO copolymers (emulsifier 30 RDP, emulsifier 31, emulsifier 32). Most systems require a mix of anionic and nonionic stabilization mechanisms for robust alkyd emulsification. Emulsifier 11 and emulsifier 21 contain ≈66% and ≈55% renewable carbon, respectively, and emulsifier 21 can function effectively as a sole emulsifier.

The emulsification process was conducted in a multi-neck round bottom flask immersed in an oil bath, with emulsification temperature selected based on the alkyd resin’s viscosity. Batch size was ≈200 g. Anionic and nonionic surfactants were added to the preheated alkyd resin and stirred for 30–45 minutes to ensure homogenization. Different neutralizing agents (NA) were tested such as KOH, LiOH and AMP95 at different degrees of neutralization (DN). Water was then added dropwise under constant stirring until a 55% solid content was reached. Phase inversion (PI) was monitored via the torque profile on the overhead stirrer. The geometry of the stirrer was anchor type.

The emulsion particle size was evaluated both before and after one month of accelerated aging at 50 °C. Selected emulsions were formulated into clear coats with a wet thickness of ≈120 µm (cured at 23 °C and 50 % RH with 0.3 and 0.5 wt % Borchers’ OXY-Coat 1101) to assess König hardness, drying behavior and chemical resistance. Hardness was measured on the same films at day 1, 14 and 28. Drying was recorded continuously over 48 hours under the same conditions. Chemical resistance was determined on films aged ≥24 hours (plus 2 hours recovery) by placing 25 mm diameter filter papers saturated with distilled water, 48% ethanol, 5% HCl or 5% NaOH onto the film surface, covering with a glass lid and scoring residual damage on a 0–5 scale (5 = no visible attack).

Results and Discussion

Study 1: Influence of Mixing Hydrodynamics, Emulsification Temperature and Neutralization Parameters on CPI Emulsion Performance

Before examining the effect of emulsification parameters, we considered the impact of hydrodynamic conditions on CPI emulsification. Perstorp emulsification experience across a wide spectrum of short-, medium- and long-oil resins indicates that in a laboratory setup an anchor-type impeller (dimpeller/dvessel ≈ 0.8) operating at low speed (≈50–100 rpm) delivers the greatest versatility, reliably producing fine, stable emulsions regardless of resin type. In contrast, we found that an Intermig impeller (dimpeller/dvessel ≈ 0.9) at 200–300 rpm, despite one report advocating its beneficial use (Ref. 1) in alkyd emulsions, tends to lock in double-emulsion structures due to the very high shearing conditions (Ref. 2), yielding only a very thick cream-like dispersion with highly viscous short-oil alkyds. Although full data are not included here, these observations indicate that excessive shear can inhibit catastrophic phase inversion in high-viscosity systems. Finally, from an operational standpoint we recommend avoiding the vortex extension above the impeller tips prior to water addition because bulk circulation and axial mixing are reduced, which compromises mass transfer and surfactant transport to the alkyd/water interface.

Emulsification temperature critically influences both the bulk rheology of the alkyd resin and the interfacial behavior of surfactants, especially nonionics. As temperature increases, resin viscosity decreases, improving mixing, mass transfer and surfactant diffusion to the oil–water interface while oil–water interfacial tension drops, facilitating droplet deformation and breakup under shear. Nonionic surfactants, however, are also affected by the emulsification temperature since depending on their cloud point (which is strongly affected by the presence of anionic surfactants or salts) they can have different phase affinity toward the oil or the water phase, either facilitating or obstructing the phase inversion. To balance these factors, we recommend a preliminary temperature sweep in a rheometer to identify the 5–20 Pa·s viscosity window, ideally between room temperature and 85 °C, with a target of 10–15 Pa·s. If this window cannot be reached without exceeding the 100 °C temperature limitation, a two-stage approach may be used: begin emulsification at elevated temperatures near 100 °C to reduce resin viscosity, then lower the temperature as soon as 10% water is added. Usually in this process extra hydrophilicity is needed, which can be provided either from the surfactant side or by working at higher neutralization degrees. For very long-oil alkyds with very low viscosity at room temperature, emulsification can usually be performed without heating.

The acid and hydroxyl values of an alkyd resin dictate its overall polarity, with carboxylic acid groups becoming ionized upon base neutralization and rendering the resin water-dispersible. Consequently, the DN is a key emulsification parameter: higher DN increases hydrophilicity while lower DN preserves hydrophobic character. We recommend fixing DN early in formulation, with 40% as a practical starting point, before screening emulsifier compatibility. Although neutralizing agents are often treated as interchangeable, Study 1 results depicted in Table 2 demonstrate that the choice of NA and DN together determine not only the ability to achieve sub-300 nm droplets but also the performance of the clear coating.

In our model alkyd–emulsifier system, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1, the tertiary amine AMP95 consistently produced the finest median droplet sizes, the best long-term heat stability, particularly at DN ≥70%, and superior clear-coat metrics (drying time and chemical resistance). Potassium hydroxide (KOH) provided an acceptable sub-300 nm emulsion at DN =40% and good heat stability but lost robustness at DN =60%, while lithium hydroxide (LiOH) failed to maintain stability under all tested DN levels, yielding multimodal size distributions and phase separation after aging. Neutralizer chemistry and DN had minimal effect on König hardness, remaining essentially constant for an 8% emulsifier loading, but led to as much as a 70% variation in total drying time as shown in Figure 1 (10 h for AMP95 vs. 30 h for KOH). Across all systems, AMP95 also delivered the highest resistance to water, ethanol, NaOH and HCl, with optimal chemical resistance typically observed around DN =40%. Given AMP95’s pending regulatory reclassification (Repr. 1B, H360; STOT RE 2, H373), alternative amine-based neutralizers should be explored.

Study 2: Performance Comparison of Biobased, Fossil-Based and Benchmark Emulsifiers

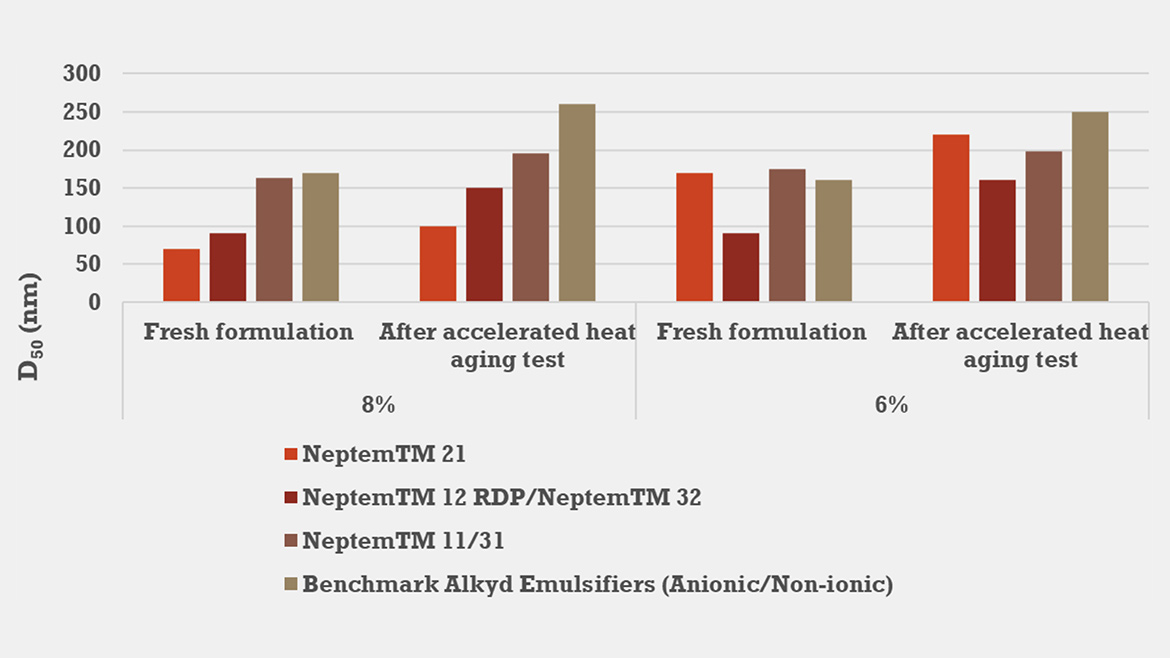

Figure 2 demonstrates that emulsifier 21 — our ≥50% renewable-carbon surfactant — delivers emulsification performance similar to both fossil-derived alternatives (emulsifier 12 RDP/32) and a commercial benchmark alkyd emulsifier blend (anionic/nonionic) at 8% and 6% loadings. All systems yielded similar initial droplet sizes and comparable particle size after one month at 50 °C. The emulsifier 11/31 blend (66% renewable carbon in emulsifier 11) also matched these results in terms of particle size and thermal stability. Crucially, emulsifier 21 achieved this performance as a sole emulsifier, confirming that a high-renewable-content anionic surfactant—stabilized with nonionic technologies—can fully replace fossil-derived blends and benchmark products without compromising emulsion particle size or heat stability.

Study 3: Compatibility of Emulsifier Selection with Different Alkyd Chemistries and Effect on Clear-Coat Performance

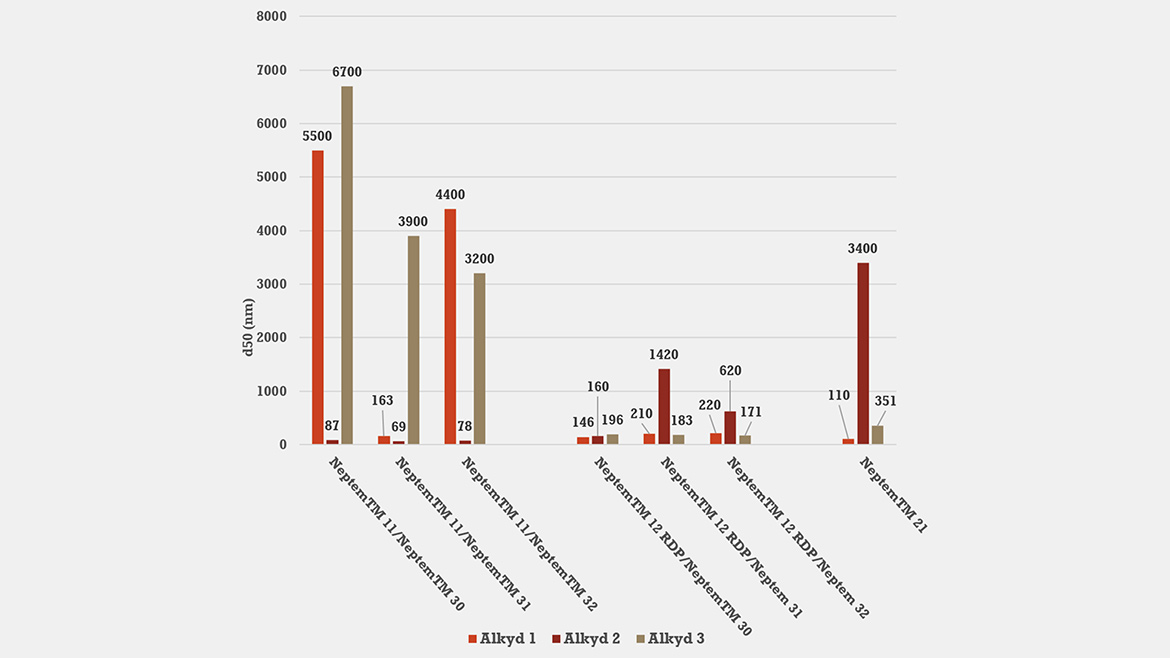

Under identical CPI conditions (55 °C, 54% solids, 8% total surfactant concentration, DN =40%, AMP95 neutralizer), we evaluated seven emulsifier combinations against three medium-to-long-oil alkyds (Alkyd 1–3). As Figure 3 illustrates, there is no single “universal” surfactant; each resin demanded a specific emulsifier combination with different anionic and nonionic chemistries to achieve stable sub-300 nm dispersions. For example, Alkyd 2 only achieved low d₅₀ with emulsifier 11 + nonionic EO/PO grades (emulsifier 30 RDP, emulsifier 31, emulsifier 32); it did not invert with emulsifier 21 alone and performed poorly with most blends containing emulsifier 12 RDP. Alkyds 1 and 3 displayed distinct emulsifier compatibilities as well, underscoring the need for a versatile portfolio spanning anionic and nonionic chemistries and a range of hydrophilicities.

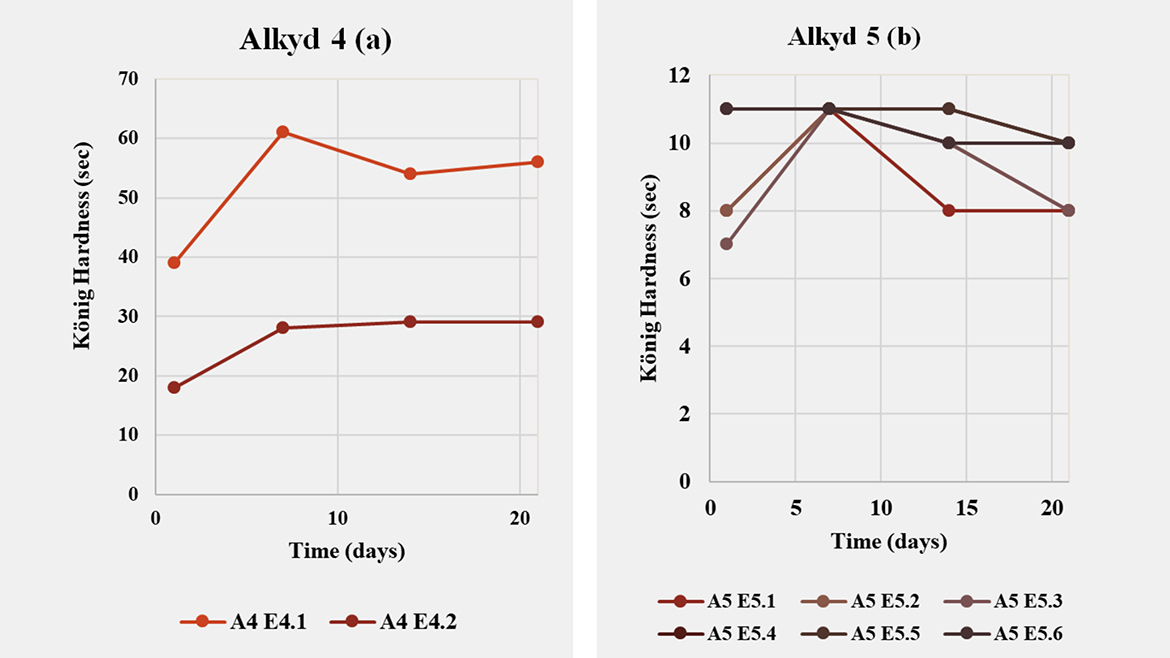

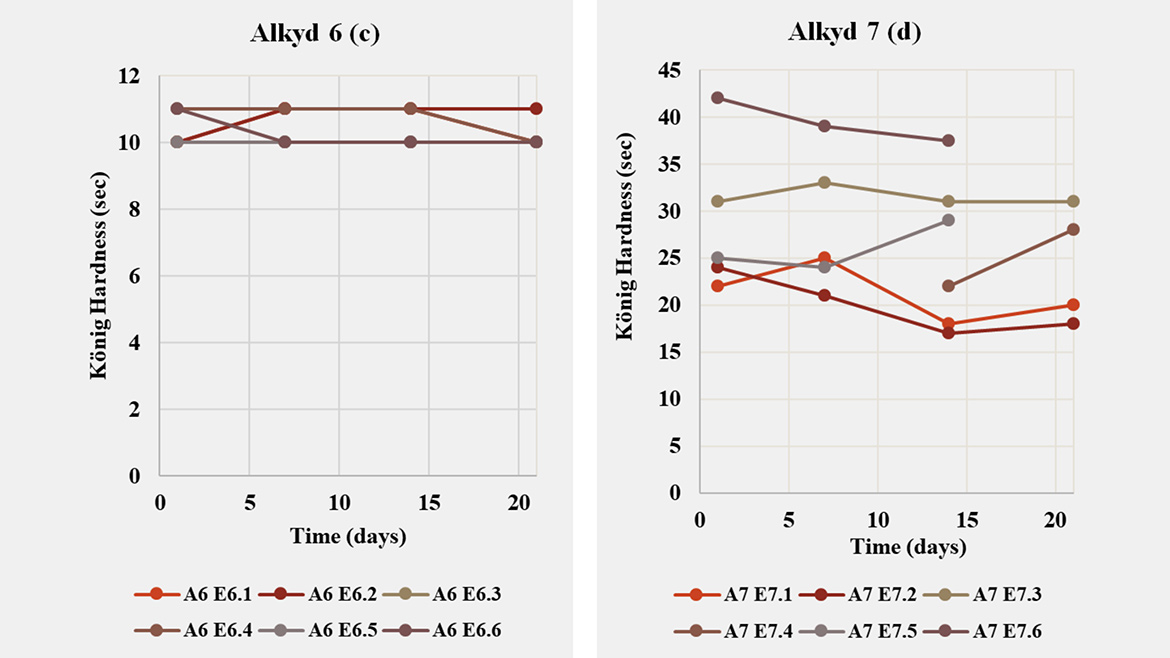

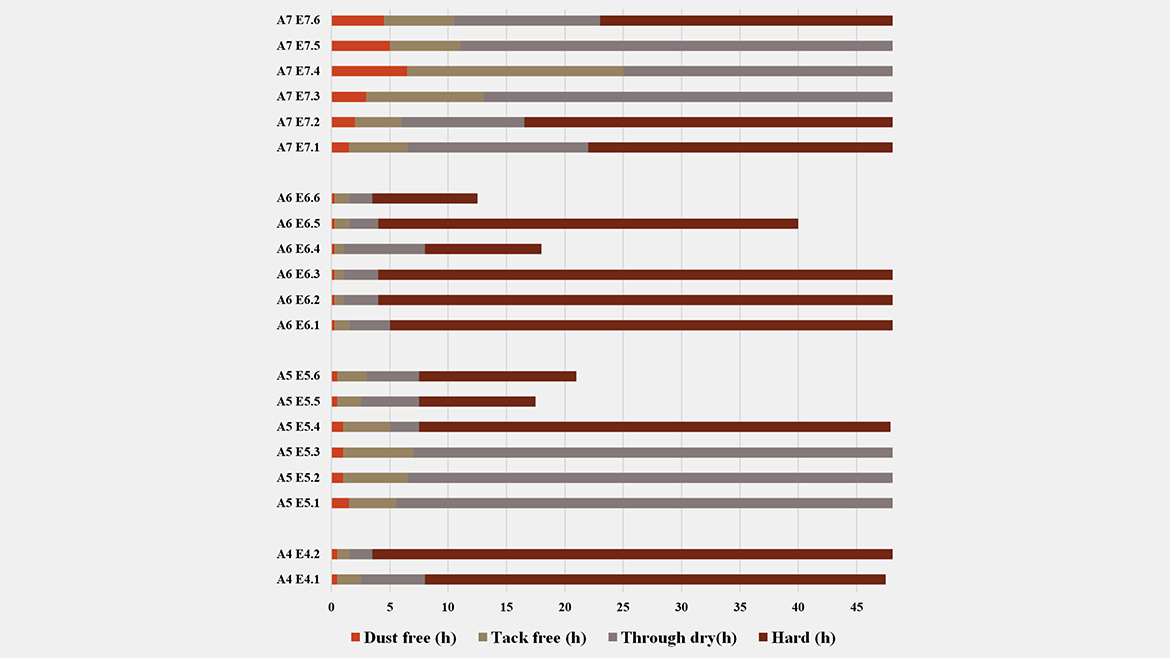

Expanding the screening to clear-coat films (Table 3; Figures 4–5) shows that performance is both emulsifier- and resin-dependent. For Alkyd 4 and Alkyd 7, König hardness and drying time varied markedly with emulsifier choice and degree of neutralization (DN). In contrast, Alkyd 5 and Alkyd 6 were largely insensitive in hardness (≈10 s over 1–20 days) yet exhibited large differences in dry-through and hard-dry, indicating that for these MLO resins the emulsifier/DN combination tunes cure kinetics far more than clear-coat stiffness. A notable case is Alkyd 7: although successful inversion was achieved with emulsifier 21 at 3wt% (DN =100%), an alternative route using emulsifier 32 alone at 6wt% (DN =100%) delivered higher hardness and a faster drying profile. This underscores that selecting the most compatible emulsifier for a given resin can outweigh simply lowering surfactant level, a common strategy to minimize emulsifier plasticizing effect. Across all resins, drying time was the most influenced metric: changing the emulsifier blend (for example 11/30 RDP vs. 12 RDP/30) or increasing DN from 40%→100% produced multifold shifts in dry-through and hard-dry, even when fresh d₅₀ values were similar (≈170–200 nm). This decoupling highlights the central role of interfacial chemistry and counter-ion effects in oxidative curing.

In summary, alkyd architecture largely defines the clear-coat performance window, while emulsifier chemistry and neutralization select the operating point within that window. Successful waterborne design therefore starts with choosing the right resin for the target application, followed by co-optimization of emulsifier type/loading and DN to balance hardness, drying and stability. Importantly, this corrects a common misconception: when performance falls short, the root cause is not necessarily the surfactant — resin structure often sets the limit. Taken together, these findings make a clear practical recommendation: surfactant selection cannot follow a one-size-fits-all approach; formulators should maintain a versatile portfolio of anionic and nonionic options spanning hydrophilic–lipophilic balance and ionic strength to reliably emulsify diverse alkyd chemistries and translate emulsion quality into robust film performance.

Study 5: Effect of Emulsifier Selection on Paint Performance

To assess downstream application performance, we formulated Alkyd 1 emulsions into a standard testing trim-paint formulation to probe the influence of emulsifier chemistry on final coating behavior. Alkyd 1 and the paint formulation were chosen as a model system to isolate the effect of surfactant selection rather than to pursue optimized paint properties. All sub-300 nm emulsions were evaluated for viscosity, pH, yellowing index, gloss, König hardness, drying time and chemical resistance (Table 4).

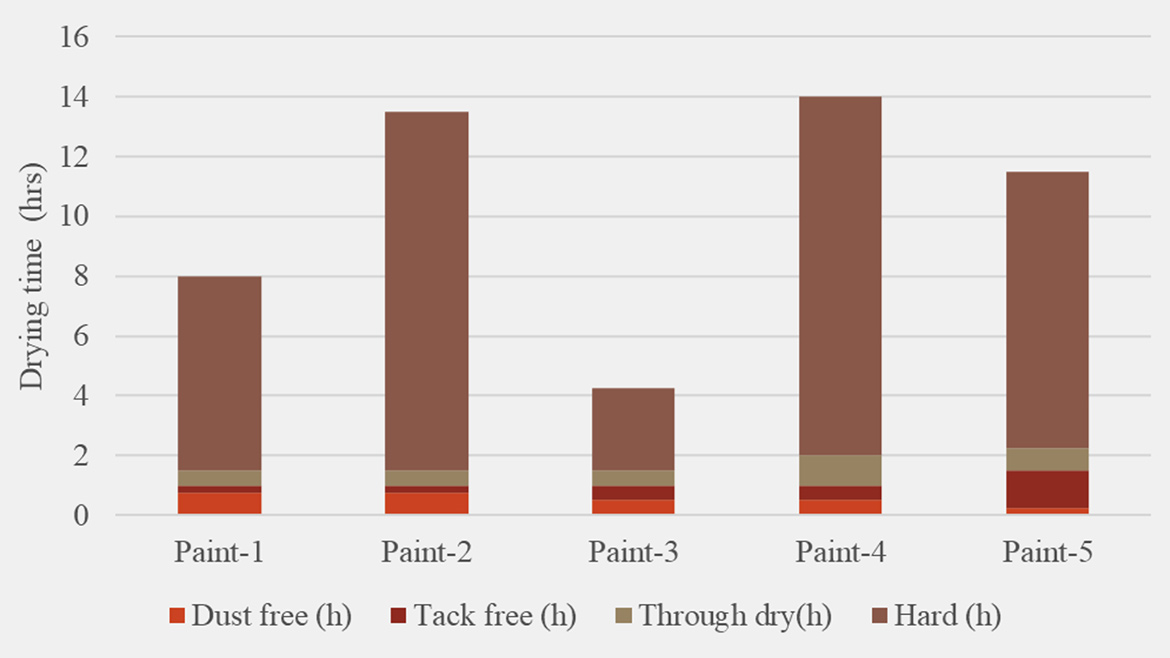

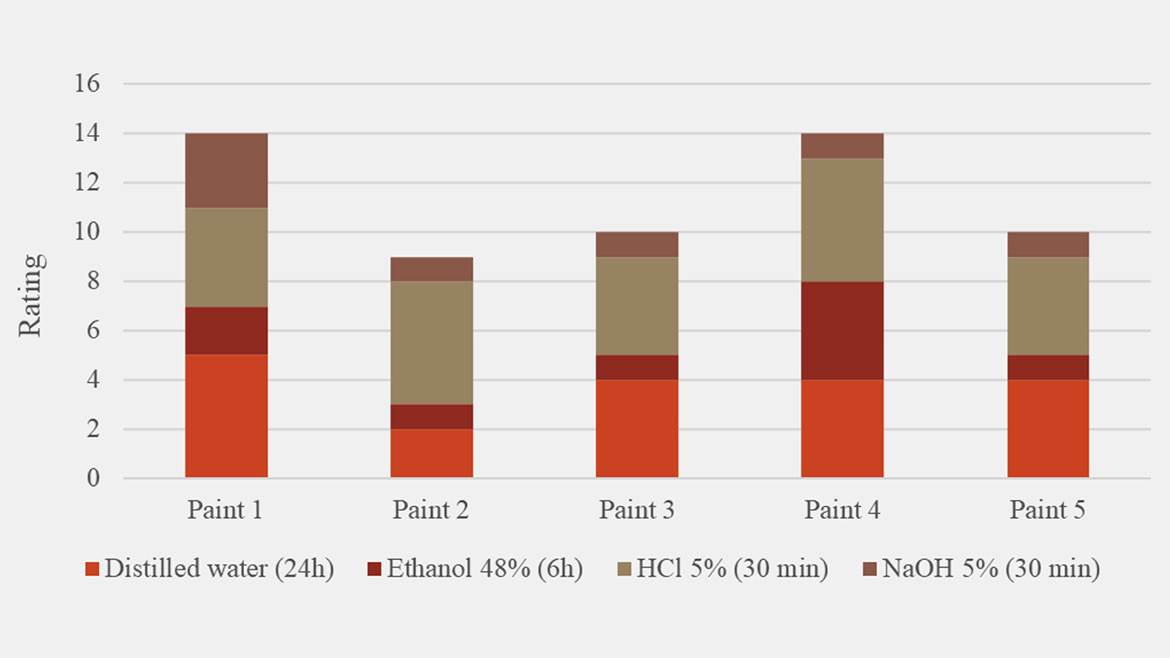

When droplet size was held constant, viscosity, pH, yellowing, gloss and hardness remained effectively unchanged across all surfactant systems. By contrast, two critical application metrics like drying time and chemical resistance varied: drying times (Figure 6) spanned from 10 h to 30 h (a 65% difference between Paint 3 and Paint 4), indicating that some emulsifiers substantially accelerate or retard oxidative cure. Specifically, the most hydrophobic surfactant blends used in Paint 1 and Paint 3 achieved the fastest cure and the most hydrophilic blend used in Paint 2, 4 and 5 showed the opposite. Chemical resistance (Figure 7) to water, ethanol, HCl and NaOH also showed distinct emulsifier-dependent trends but without a straightforward link to surfactant hydrophilicity. Interestingly, Paint 4, stabilized with the most hydrophilic nonionic emulsifier (emulsifier 30 RDP), also exhibited the highest chemical resistance. This indicates that, depending on resin structure and paint formulation ingredients, synergistic interactions among the emulsifier, alkyd and other components can mitigate a surfactant’s inherent water affinity and maintain the coating’s protective function. Across the full spectrum of surfactant chemistries, for Alkyd 1, emulsifier 21 — the emulsifier with ≥50% renewable content — demonstrated the most balanced performance across all paint application properties measured in this study.

Finally, Figure 8 maps the diverse oil lengths, hydroxyl numbers and acid values of the alkyds successfully emulsified using the emulsifier grades presented herein — comprising both commercial and RDP grades — under tailored CPI conditions. This demonstrates that combining hydrophilic and hydrophobic, anionic and nonionic surfactants with optimized emulsification conditions provides the versatility needed to emulsify a broad spectrum of alkyd chemistries into stable waterborne emulsions.

REFERENCES

- Aksoy, P.; Çiftçi, S. Impact of Phase Inversion and Process Parameters on Alkyd Emulsion Properties. Eur. J. Res. Dev. 2025, 5 (1), 1–16.

- Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Wen, L.; Yin, Z. Incomplete Phase Inversion W/O/W Emulsion and Formation Mechanism from an Interfacial Perspective. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 2018, 39 (1), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/01932691.2017.1300909

- Lefsaker, M. Characterization of Alkyd Emulsions: Characterization of Phase Inversion and Emulsification Properties Pre- and Post-Inversion; Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013.

- Weissenborn, P. K.; Motiejauskaite, A. Emulsification, Drying and Film Formation of Alkyd Emulsions. Prog. Org. Coat. 2000, 40, 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9440(00)00120-X

- Pierlot, C.; Ontiveros, J. F.; Royer, M.; Catté, M.; Salager, J.-L. Emulsification of Viscous Alkyd Resin by Catastrophic Phase Inversion with Nonionic Surfactant. Colloids Surf. A 2018, 536, 113–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2017.07.030

Learn more about waterborne coatings through PCI’s dedicated topic resource page.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!