Achieving More Success in New Product Development

Developing truly new products aimed at new customers and new markets is hard, but if your company wants consistent, top-line revenue growth, you must get good at it. This article - the first in a series of four - will illuminate the new product development challenge, giving you a deep understanding of what makes it so difficult. Follow-on articles will provide you with six practical keys to overcome these challenges. My firm extracted these keys from 15 years of new product development experience working on hundreds of projects at global manufacturing companies; they work because they make you better at three critical tasks: (1) asking the right questions at the right time during new product development, (2) minimizing your spend (in time and resources) on ideas that are unlikely to find market success, and (3) delivering the data decision-makers need to confidently make large investments in the best ideas.

The keys are, essentially, the “first principles” of new product development and will complement any product development process: this series will not recommend sweeping changes to your culture, the implementation of new stage gate steps, or anything else that is expensive, invasive or time consuming. Instead, the keys will work within your existing processes, acting as a philosophical and process overlay that will make what you already do function more effectively.

Understanding Innovation

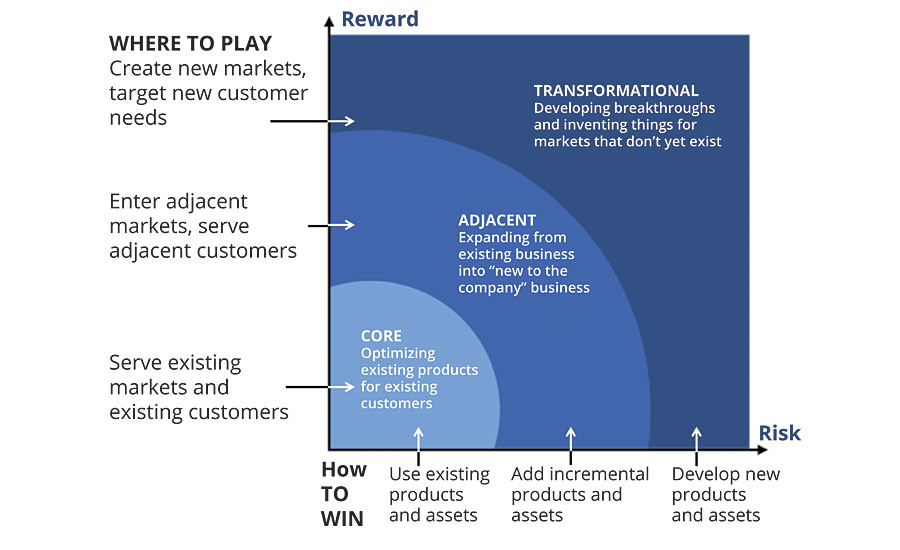

Let’s begin with some vocabulary so we are all speaking the same language, particularly when it comes to innovation. “Innovation” is a word that has been so over-used, many of us are tired of hearing about it. But if we are going to get truly new products into the market, we need to be able to talk about it clearly. You may call them something different at your company, but there are three types of innovation: core, adjacent and transformational. You will recognize the archetypes in Figure 1 - adapted from Managing Your Innovation Portfolio, Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff, Harvard Business Review, May 2012 - and in their descriptions below.

Core Innovation

Core innovation is what established companies do all the time, and most are pretty good at it: making existing products better based on customer feedback, competitor activity and industry trends. Core innovation is always aimed at existing customers in markets where you already participate, and doing it well allows you to preserve your market share (and, therefore, your revenue base). When a customer asks you to modify a coating, and the new formulation becomes part of your product line, that is a core innovation.

It’s hard - if not impossible - to grow doing nothing but core because many of the core innovations you launch wind up cannibalizing the sales of the product they are replacing. Although you can sometimes increase the sales of existing products through marketing or a particularly effective sales push, sustained, long-term growth does not come from your current products; instead, it comes from selling new products that expand your revenue base. This is where adjacent and transformational innovation become important.

Adjacent Innovation (Existing Customers)

This type of innovation is aimed at selling genuinely new products to existing customers; it expands your revenue base. Said differently, this is “new to the company” business even though you are selling to customers you know well. Adjacent Innovation (existing customers) is harder to do than core because there is more uncertainty involved: you are addressing customer needs you don’t understand as well as the current needs you fill. A customer might say, “You guys are really good at additives, but only for paints. We need a concrete additive that will delay curing times; is that something you think you might be able to help with?” If your company decided to pursue this opportunity, this would be an adjacent innovation (existing customers), employing new technology to fill the needs of an existing customer.

Adjacent Innovation (New Customers)

Adjacent innovation (new customers) is aimed at selling existing (or slightly modified) products into genuinely new markets; it expands your revenue and customer base. Said differently, this is “new to the company” business involving customers you do not currently serve. Adjacent innovation (new customers) is harder to do than both core and adjacent (existing customers) because uncertainty continues to climb. When you are selling new products to existing customers, you can talk to them, fully understand their needs, and - in fact - consult with them in the development process. When you are dealing with entirely new customers, however, gathering the information needed to ensure the new product will serve a genuine market need is more difficult. If you were a specialty coatings company focused on demanding aerospace applications and discovered that minor modifications to your formulas would make your coatings suitable for high-end automotive applications, this would be an adjacent innovation (new customers), employing modest modifications to existing products to sell to entirely new customers.

Transformational Innovation

Transformational innovation involves creating genuinely new products aimed at new-to-the-company customers. It’s harder to do than both core and adjacent because, again, the uncertainty level is higher. And this means there is greater risk. When you launch a core innovation, you have a high level of confidence in its success because, in most instances, a customer or the market told you that they want the innovation. When you get all the way out to transformational, however, you are trying to locate customer needs that no one is filling yet and, usually, develop solutions using technologies that are also unfamiliar to you. This is a tall order. But launching transformational innovations can generate significant returns because - when you can pull it off - you are either creating a market for the first time or bringing a novel solution into an existing market.

These terms for innovation will be employed throughout this series, and - using them - let’s move on to understanding a little more about why non-core innovation is so difficult.

A Different Approach is Necessary

The primary reason that companies fail to launch adjacent and transformational innovations is simple: they treat every potential opportunity in the same way, whether it is a simple modification to an existing product (core) or something radically new (transformational). While having a single process for all product development seems attractive, it doesn’t work: corporations have an insatiable appetite for certainty, and innovations aimed at new customers and new markets are inherently uncertain; the corporate immune response to this kind of uncertainty is to retreat to the safe and known. It’s an understandable impulse, but - over time - it will cause your growth to slow and then stall entirely. A different approach to the same process is necessary to succeed in adjacent and transformational innovation.

If you throw an adjacent or transformational idea into the same pile (fighting for the same budget) as a core innovation that a large customer requested, the ideas with more uncertainty - and therefore more risk - will always lose. The keys presented in the second article in this series will specifically address techniques that can be used to ensure that your product development process does not become a core-only process because of this uncertainty mismatch, but this raises a new question: other than just using your gut, how can you know when an idea should be treated differently because of its uncertainty level? Thankfully - and without getting too granular - it’s easy to divide projects into core and non-core piles so you can take appropriate steps to protect the non-core projects from the corporate immune response to uncertainty.

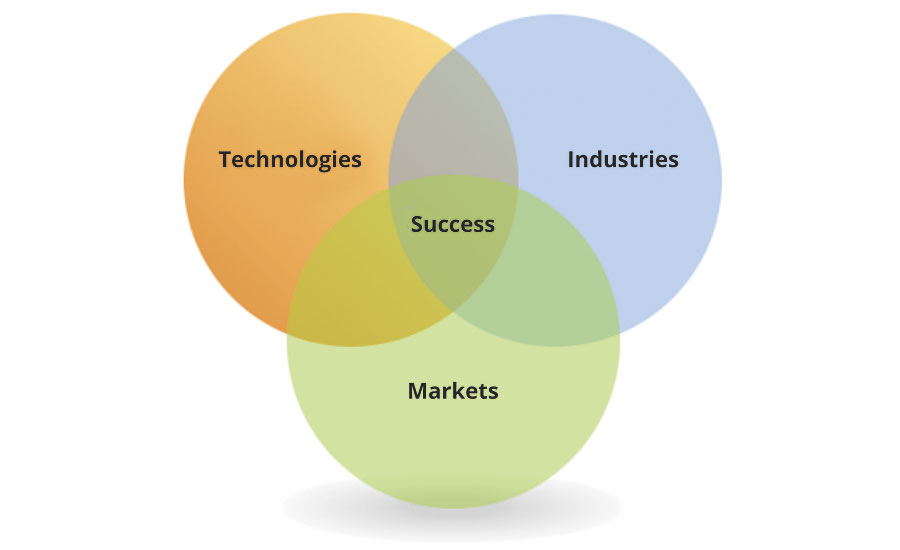

If you think about your successful, existing products, they all have one thing in common: they live in the center of the Technologies, Industries (competitors) and Markets (TIM) Venn diagram depicted in Figure 2: they contain a competitive technology (or feature set), there is a need for them in the market, and you match up well against your competitors in the industry. But they have something else in common: you have a robust understanding of all three domains, the ecosystem where your products compete and win. Because you understand the TIM landscape completely, it’s easy to develop an ROI and a complete business plan for any proposed core innovation. In other words, you have certainty.

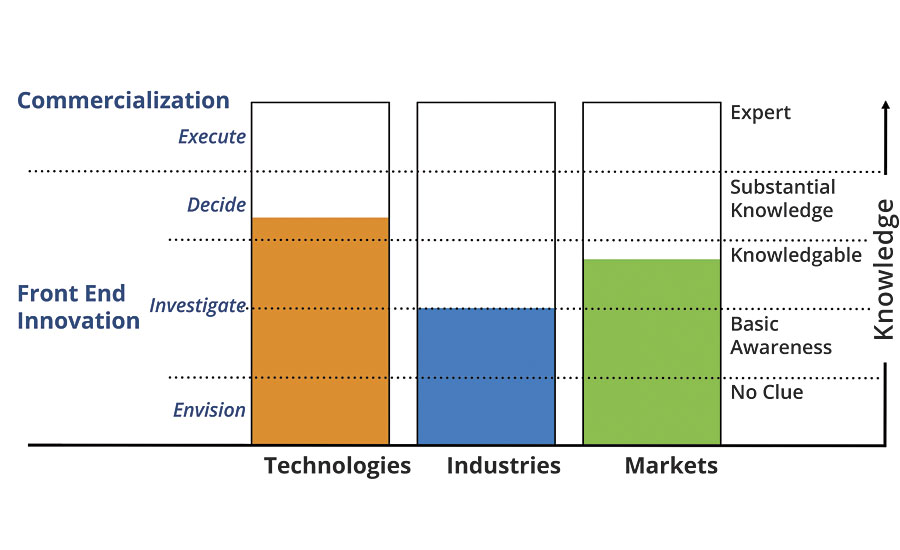

Here, then, is how you know when an idea is non-core and will need to be treated differently until it is ready for your final push to commercialization: when your understanding of TIM falls below the “Substantial Knowledge” line in Figure 3. When this happens, you are in what business academics call Front End Innovation, and the idea has almost no chance of survival if it is managed like a traditional core project. “Substantial knowledge” is a nebulous term, and that is purposeful because its meaning will vary from company to company and from leader to leader; you know you have reached the “substantial knowledge” line when the relevant decision maker has enough information to confidently make a major investment in the new product idea.

Front End Innovation

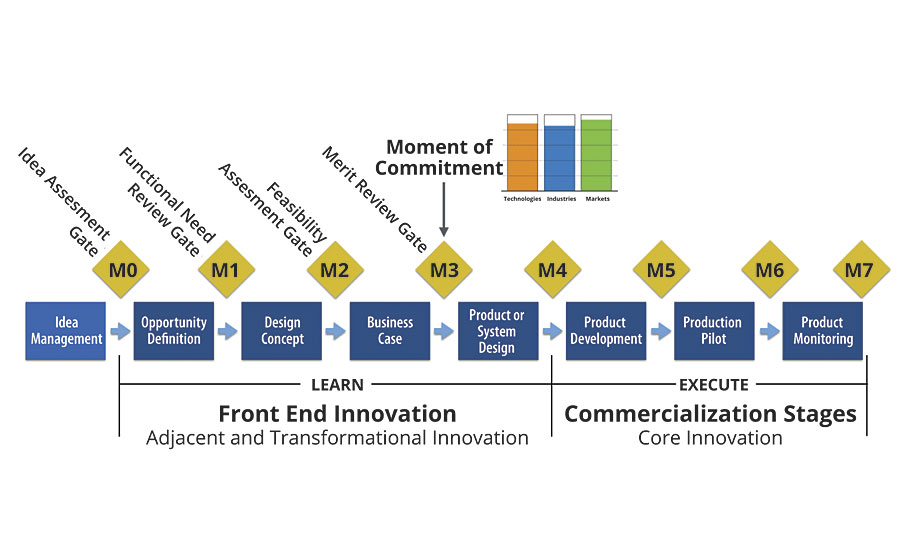

Now that you have a sense of what projects need to be protected - those that are in the Front End - let’s take a look at when they need to be protected through the lens of a typical stage gate process similar to the one that is likely in use at your company (Figure 4). The stage gate process has steps, and one of these conceptually divides the new product process from “we might launch this” to “we are absolutely launching this absent a major surprise.” This dividing line - the gate in which the generic stage gate process moves from “Business Case” to “Product or System Design” - has two unique characteristics: (1) after the line (which we call the Moment of Commitment) you are going to expend substantial sums on getting the idea to market, and (2) you are willing to make these expenditures because you have a high degree of certainty about the product’s ultimate success. In other words, you have Substantial Knowledge in every TIM domain.

Before the Moment of Commitment for adjacent and transformational initiatives, you are in the Front End, and the idea needs to be treated differently. Before the Moment of Commitment (MoC), you are learning. After, you are executing. It’s important to note that many core innovations spend some time in the Front End because there are likely to be some uncertainties that need to be addressed. For instance, when 3M decided to start making Post-it notes in colors other than yellow, it needed to make sure that the paper could take different dye colors, that the cost of the dye would maintain expected margins, etc. This was a classic example of a core innovation, but there were some Front End questions to address.

If you refer to Figure 3 for a moment at this point, you will notice that the Front End can be roughly divided into three phases: Envision, Investigate and Decide. This is simply a general measure of how far the project is from the Moment of Commitment, and Front End projects can be kicked-off at any of these stages. While these three phases are roughly equivalent to Opportunity Definition, Design Concept and Business Case phases in the generic stage gate, philosophically it can be useful to think about adjacent and transformational initiatives using the envision | investigate | decide framework to help ensure you are working on the right questions at the right time. This idea will be developed more fully in the follow-on articles.

Envision Stage Projects are those where your understanding is quite low in one or more of the TIM domains. This is an indication that you need to focus early project efforts on increasing your knowledge in the areas of lowest understanding, because rapidly increasing your areas of low understanding will lead most readily to making a properly informed decision to invest further time and resources in the project or to intelligently halt it.

Investigation Stage Projects are those where your understanding is in the heart of the Front End but not yet advanced enough to make major investment decisions. Most of your Front End work will be in the investigate stage and will involve gradually increasing corporate knowledge in all three TIM domains.

Decide Stage Projects are those getting very close to having enough information (ROI calculations, business plans) to make a decision to commit significant resources to the project.

Conclusion

To summarize, before the Moment of Commitment in your product development process, adjacent and transformational new product development efforts - efforts that are absolutely critical to your long-term growth - can be hampered or destroyed by the inherent uncertainty that surrounds them. By recognizing the corporate immune threat to these projects and applying some practical techniques, you can advance more of them into your commercialization pipeline and drive consistent growth. Now that this background is out of the way, the next article in the series will cover the first two GrowthPilot keys: maintaining a balanced innovation portfolio and providing a protected budget for adjacent/transformational initiatives.

For more information, e-mail Bill Weber Bill.Weber@growthpilot.com.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!