New Product Development Success Keys

The first article in this series of four, Achieving More Success in New Product Development, illuminated the new product development challenge, giving you a deep understanding of what makes it so difficult. It provides helpful background for what is discussed below, and you can find it online at pcimag.com or in the December 2018 print edition.

The series is based on work my firm did over the last 15 years on hundreds of new product development projects at global manufacturing companies. In the course of that work we extracted six practical techniques that can help you achieve consistent, long-term revenue growth. The GrowthPilot keys work because they make you better at three critical tasks: (1) asking the right questions at the right time during new product development, (2) minimizing your spend (in time and resources) on ideas that are unlikely to find market success, and (3) delivering the data that decision makers need to confidently make large investments in the best ideas. This article will describe the first two keys: maintaining a balanced innovation portfolio and providing a protected budget for adjacent/transformational initiatives. Follow-on articles will address the other four keys.

Let’s begin by expanding our discussion of the broad categories of new product development ambition so that we can get to the center of the challenge: how should you balance these categories to achieve maximum success? You may call them something different at your company, but there are three types of innovation: core, adjacent and transformational:

- Core innovation is what established companies do all the time, and most are pretty good at it: making existing products better based on customer feedback, competitor activity and industry trends.

- Adjacent Innovation is aimed at selling genuinely new products to existing customers or selling existing (or slightly modified) products into genuinely new markets; it expands your revenue base. It is sometimes useful to think of these two classes of adjacent innovation separately: finding new markets for your existing products is a very different challenge than creating new products for your existing customers.

- Transformational Innovation involves creating genuinely new products aimed at new-to-the-company customers.

These categories have been discussed as a useful innovation framework for a long time, but simply sorting your growth ideas into piles does little good if it doesn’t help generate new revenue. Bansi Nagji and Geoff Tuff - consulting executives and partners in the Monitor Group - deeply researched this problem and published their findings in the May 2012 issue of the Harvard Business Review in an article titled Managing Your Innovation Portfolio. The article is important and should be read, but I will summarize their findings briefly before discussing what you can do to actually implement their insights at your company.

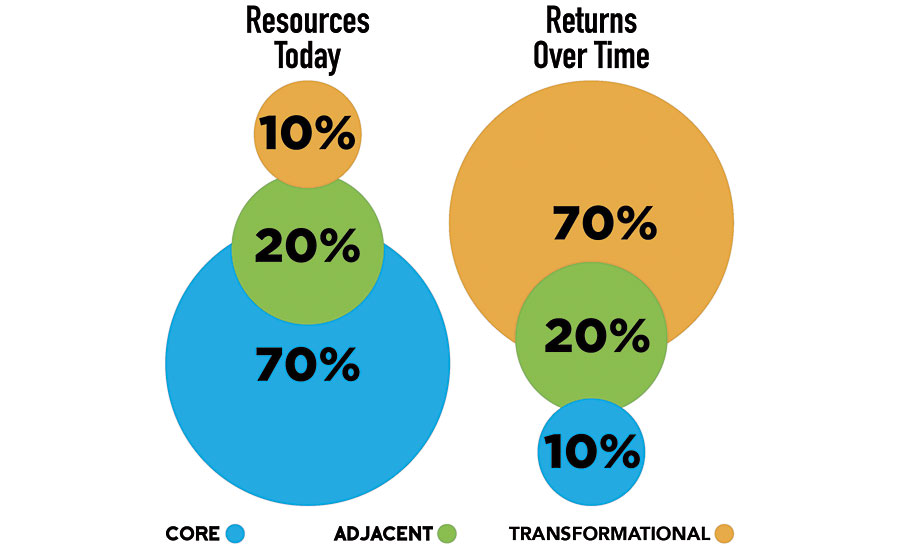

A 70-20-10 Balance

Nagji and Tuff studied a broad group of companies in the industrial, technology and consumer good sectors, and the data revealed a pattern: companies that devoted 70% of their innovation activity to core initiatives, 20% to adjacencies and 10% to transformational ideas realized a 10% to 20% P/E ratio premium over their less deliberate peers. Even more significantly, over time the revenue benefit companies achieved by using a 70-20-10 portfolio balance was the inverse of their innovation spend: 70% of their returns came from the 10% they spent on transformational initiatives, 20% came from adjacencies and 10% came from core (Figure 1). Playing it safe is not going to get you the growth you want.

More consistent growth and better returns is the carrot for making the move to a strategically balanced portfolio, but it is also worth discussing the stick: market irrelevance. Imagine your business as a storefront with a large warehouse in back; behind that is a product development center that is supposed to be stocking the warehouse with innovative new products. Today, your store is full of goods the market wants to buy, and business is good. You know the new product development center ought to be staffed, but you’re making plenty of money and can worry about that later.

Customers come in to your store, make purchases and begin to deplete your shelves. No problem. You simply head back to the warehouse and restock with more of the same. But down the street your competitors are starting to make new offerings: some are upgrades to their existing products, but others are transformational innovations that are bringing more customers to their store. Your business begins to slow a little, but you generate new traffic by advertising and running sales. You maintain your margins by getting more efficient and eliminating some of your staff. With all this pressure, getting that new product development center running smoothly is just not a priority. Soon, though, your customers are beginning to demand what your competitor down the street is delivering. But when you head to the back of the warehouse for new products there is nothing there. You had a good run, but the value of your business is shrinking and you have no new tricks available to stop the slide. This is the story of every company that fails to plan for the future.

The way to avoid this fate is to strategically balance your portfolio. 70-20-10 is not, of course, right for every company, and the research goes on to point out that industry is an important factor in determining the right balance for your company. Industrial manufacturers tend to come closest to 70-20-10, technology companies - because of customer demand for the next big release - spend less on core and more in other areas, and consumer goods companies tend to spend more on core. Where you are in relation to your competitors should have an impact on your thinking, too: if you are lagging, you may need to take some bigger risks.

In our experience, other factors matter, too. If you are an industrial conglomerate with many different divisions, the same mix is not going to be right for every division. If, for instance, you have a business unit in a commoditizing industry, you may decide - for valid strategic reasons - that the BU should be managed to generate cash for as long as possible, focusing only on efficiency initiatives (which are always core). At the same time, another BU may be riding a technology wave in a fast-growing industry and have an entirely different portfolio mix. In short, you need a deliberately balanced innovation portfolio, but the right balance is going to vary by industry, by your place among your competitors and - for larger companies - by business unit.

Additional factors that you may want to consider include product lifecycles in your markets (the shorter the cycles, the more your portfolio mix should shift toward adjacent and transformational opportunities), your growth goals (the more aggressive your goals, the more you need to shift away from core), and the state of your current product development (if it is unclear what you will be selling two years from now or if new competitive threats are emerging, give more weight to adjacent and transformational opportunities).

While Nagji and Tuff empirically validated the importance of a balanced portfolio to growth, their work is not intended to provide a practical guide to implementation. Given the scale of new product development efforts at large companies, how do you decide what 70% of your “innovation activity” actually is? Who decides the proper balance and what factors should go into that decision? How do you measure success outside of your core? How do you manage the process? We’ve answered these questions and more like them in the course of our work with a wide variety of clients in different industries, and that is what I’ll turn to next.

Managing Your Projects

Once you have decided the mix that is right for your company given your strategic growth goals, the next question is one that Nagji and Tuff do not address: how do you work the projects in your portfolio? The best solution usually involves a hybrid approach, with certain kinds of projects being worked at the business unit level and others being worked by a special group at the corporate level.

First, business units should manage all core projects and adjacencies aimed at developing new products for existing markets. The business units know their customers’ needs best and will be able to execute. Further, most of these projects fit naturally into your existing stage gate process and support the quarterly revenue goals that tend to drive business unit thinking.

A corporate group should manage all transformational projects and adjacencies aimed at moving existing products into new markets; all these projects involve unfamiliar customers, and the skillset needed to execute them effectively is different. This point will be expanded significantly in the next article in this series.

Keeping the development of early-stage adjacent (new customers) and transformational projects out of the business units avoids three problems: (1) money spent within the business unit on long-term, transformational projects will dilute their margins, and this creates headwinds for the most promising long-term growth opportunities, (2) business units can be so close to their markets that they have difficulty generating transformational ideas, and (3) business units tend to rely on customer feedback for innovation ideas, but - for transformational initiatives - customers don’t know that they actually want things that do not yet exist.

This hybrid approach is not a perfect solution, of course: it can be hard to transfer new products into the business units if they did not have a hand in developing them. This issue exists at every company, but it manifests itself in too many different ways to be covered here. In general terms, however, the solution is to ensure that - as development of adjacent and transformational initiatives by the corporate group advances - the group starts getting the business units involved as soon as it become apparent that an idea is genuinely promising; by the time an initiative needs significant investment to move forward, the intended business units will have all the information necessary to support transferring the project into the company’s stage gate process for the final push to commercialization.

Deploying Resources

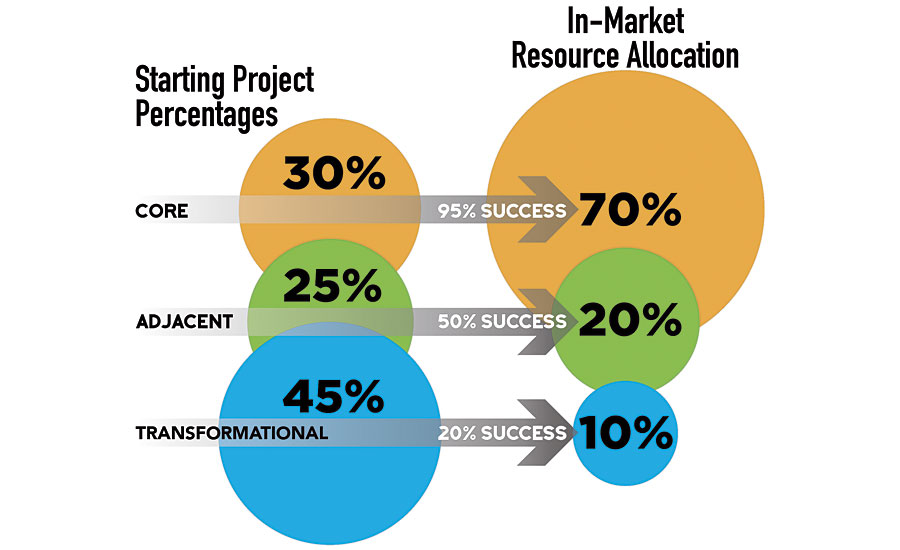

The next challenge is how to deploy resources in a way that provides metrics proving that you are hitting your portfolio goals: what does it mean to make a “resource allocation” of 70% (or any other percentage) in your balanced portfolio? It turns out that the answer to this question is much simpler than it might seem: use project numbers as a proxy combined with success rates that studies have determined over time: core projects have a 95% success rate, adjacent projects a 50% success rate and transformational projects a 20% success rate.

Referring to Figure 2, you can see how this works in more detail. The figure assumes a standard 70-20-10 allocation. To reach this number you should, over any given time period, have 30% of your innovation projects focused on core, 25% on adjacent opportunities and 45% focused on transformational opportunities. Given what your current portfolio looks like, that transformational number may seem unreasonably high, but this is not the case.

Companies tend to think of a “project” as something that gets significant funding and a lot of attention. This is NOT the way to think about it. A project is any idea that is interesting enough to devote any time or resources to investigating further. Thinking about it this way means that you will spend large sums on core projects, and this is money well spent because your confidence level is high, core projects have a high success-rate and core projects preserve your revenue base. Many adjacent projects, on the other hand, will drop out early with little money spent on them; you will have confidence in those you decide to spend money on, but the number will not be large. Most transformation projects will drop out rapidly and at little cost so you need to start with a large number. But the ones you spend real money on will be quite small.

Measuring Progress

Finally, we need to measure our progress. This is straight-forward for core projects because you are going to have a projected ROI before you launch: did it meet expectations? The measurement is different for adjacent and transformational projects, however. In the first article in this series I described the Moment of Commitment in your stage gate process, typically the gate at which you make decisions that are going to lead to large investment on a project. For adjacent and transformational projects, you should measure progress in only three ways before the Moment of Commitment:

- Project Cadence. This measure is going to differ from company to company based on your development cycles, but every project should be clearing critical uncertainties at a steady, predictable rate. If that is not happening, you need to evaluate why and fix the problem (which often turns out to be a lack of resources).

- Intelligent Learning. The pre-Moment of Commitment goal is always intelligent learning, and if the critical uncertainties you are clearing are not increasing your confidence in the idea (or convincing you to intelligently halt it because a cleared uncertainty indicates that it is unlikely to find market success), you must reevaluate the way you are identifying critical uncertainties. If the work you are putting into an idea is not teaching you anything that helps you make decisions, the work is wasted effort.

- Portfolio Balance. Are you working enough projects to meet your portfolio balance goal? Remember, the primary driver here is to start enough adjacent and transformational projects and then work them methodically; most will drop out early and many more will not make it to market, but all of that is okay: quantity comes early, and quality emerges over time.

Now we can move on to discussing the importance of a protected budget for adjacent and transformational initiatives. The problem here is obvious: core projects are always going to seem most important if you are looking at the world through a quarterly results lens because these are the projects your customers are asking for and the market is demanding right now. And they are important. But if you look at your company’s future through a longer lens - and you must do this - they are no more or less important than your adjacent and transformational efforts. In the face of demands for quarterly results, how do you force yourself to give all kinds of innovation the attention they deserve?

I’ve already discussed one technique to overcome this problem: a commitment to maintaining a balanced portfolio. This ensures that you are thinking all the time about what the right mix is for your company and that ideas are being worked across the innovation spectrum. But claiming you care about a balanced portfolio is not enough. You have to fund it.

If you put all your innovation resources - people, R&D capacity, budget - into one basket, core will always win because it will deliver short-term revenue. Your adjacent and transformational ideas will never be worked because they will constantly be bumped to the back of line by whatever product development effort your sales team says they need out the door tomorrow. My bet is that you have seen this happen hundreds of times in the course of your career: really interesting ideas never develop any momentum because no one has any time or money to work on them. Instead, you are always fighting to get the new thing sales wants out the door as quickly as possible and those interesting long-term ideas stay exactly that - interesting ideas. Forever.

The solution to this problem is to provide a protected budget to the corporate group described above whose only role is to work adjacent (new customers) and transformational initiatives. Using the techniques that will be covered in follow-on articles they can, at low cost, triage and investigate the adjacent and transformation parts of your portfolio on a dedicated basis. Over time, they will identify and develop the best of these ideas, and - when significant investment is necessary to continue their development - your team will be able to prove the money will be well spent and overcome the corporate immune response to non-core ideas.

Providing a protected budget for adjacent and transformational initiatives will not, of course, produce immediate results. Once it gets moving, however, the effort - combined with a strategically balanced portfolio - will begin to feed a steady stream of truly new products into your pipeline, ensuring both the growth you want and the long-term relevance of your company to the market.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!