The Right Team Working Only Critical Uncertainties

New Product Development Success Keys

The first, second and third articles in this series of four illuminated the new product development challenge and discussed the first four keys to sustained innovation success:

- Maintaining a balanced innovation portfolio;

- Providing a protected budget for non-core innovation;

- Managing innovation ideas differently before and after the Moment of Commitment; and

- Working with an engaged executive.

This article will describe the final two keys and then provide a reminder of how they all work together to drive predictable, sustained success in new product development. The best thing about the final two: you can begin deriving benefits from them immediately, whether your company implements the other keys or not.

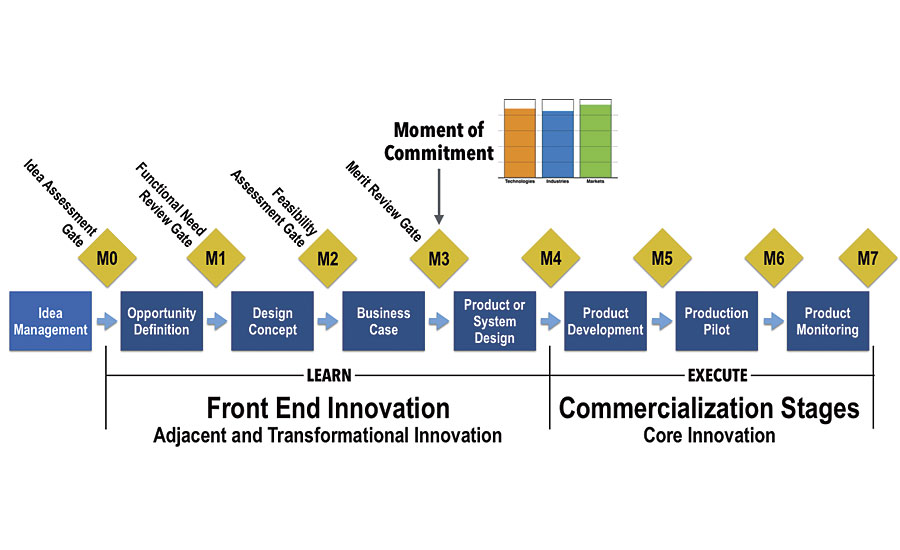

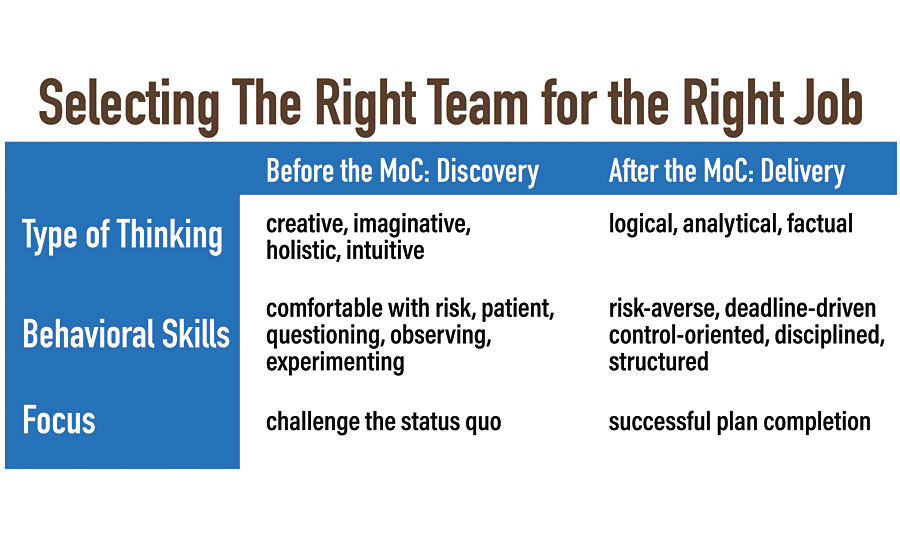

As you may recall from the last article, there is a point in your stage gate process - what we call the Moment of Commitment or MoC - that conceptually divides the new product development process from “we might launch this” to “we are absolutely launching this absent a major surprise” (Figure 1). The MoC in your stage gate has two unique characteristics: (1) after the MoC you are going to expend substantial sums on getting the idea to market, and (2) you are willing to make these expenditures because you have a high degree of confidence in the product’s ultimate success. When talking about innovation, the time before the MoC is known as the Front End. Just as you need to use different processes to achieve success pre- and post-MoC, you need to have people with different skillsets working on a project pre- and post-MoC. This, then, is the focus of the fifth GrowthPilot Key: select the right team for Front End projects.

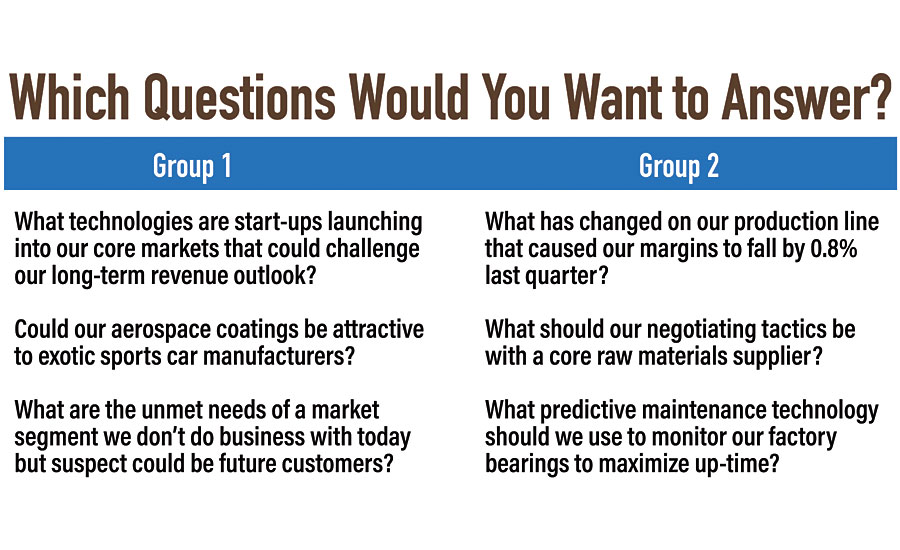

Think about the problems you like working on, the questions you like answering. I’m not talking about the work you can grind out when it’s needed, but about the kind of work you look forward to doing. Chances are you fall into one of two camps. Take a look at Figure 2. Which group of questions are most appealing? If you find the first group more appealing, you will probably enjoy and be good at Front End (pre-MoC) work. If you find the second group more appealing (post-MoC kinds of questions), you will likely find Front End work - particularly early-stage Front End work - frustrating and, sometimes, just plain stupid. So when there is Front End work to be done, you need to staff the early-stage team with people from the Discovery Group (the first group), gradually adding people from the Delivery Group (the second group) as the project progresses and certainty about the idea’s prospects begins to be reduced.

It’s easy in an innovation-focused discussion like this to get the sense that one group of people - the Discovery Group - is somehow advantaged. This is absolutely untrue. No company can run without both groups, and we should all be glad that we have our complements among our colleagues. Put a Discovery Group member in charge of a production process and the line will likely have the worst margins in the industry. Ask a member of the Delivery Group to work in the Front End, and you will likely get beautiful engineering diagrams but be left totally in the dark as to potential product-market fit. We all have our roles in the organization, and you need to get the right people working on the right problems.

Figure 3 provides more context around the characteristics of people who excel in one area or the other; there are very few who are good at both. The Discovery Group tends to contain creative scientists, designers, strategic planners and broad-gauge executives. The Delivery Group tends to contain product engineers, product managers, financial analysts, and - of course - your best Six Sigma Black Belts. Both types exist at all levels of the organization, and this is why it is critical to choose your Front End teams based on aptitude rather than based on title or position within the hierarchy. Choosing your teams this way provides you with two huge benefits: it makes your process work smoothly and it means people are doing the work they enjoy doing.

One example. Years ago, we connected a client with a global presence in the electronics industry with a leading academic researcher to develop a MEMS switch. The researcher produced four of the switches based on a novel geometry and a new alloy, and the results were impressive. We all got together for a meeting about next steps, with a relatively small group of client personnel assigned to the effort. The exec in charge - a truly broad-gauge person with a deep understanding of the Front End - had this to say, “These are really impressive results, let’s get a sense of what product lines could most benefit from this technology and why (or why not) it might be better than our current solution.” Great idea.

A senior engineer for one of the business units asked this, “What will the unit-cost be at scale?” I’m tempted to call this a bad question, but it’s not. It’s a very good question. But not in the early stages of the Front End. It must be answered, but it will be one of the last bits of information developed before the project crosses the Moment of Commitment (if it even gets that far). The exec recognized the disconnect (he was a perfect Engaged Executive as described in the last article) and moved the engineer off the team in favor of someone who was more comfortable with early-stage Front End questions. This harmed no one’s career and made the project team better.

The Final Key

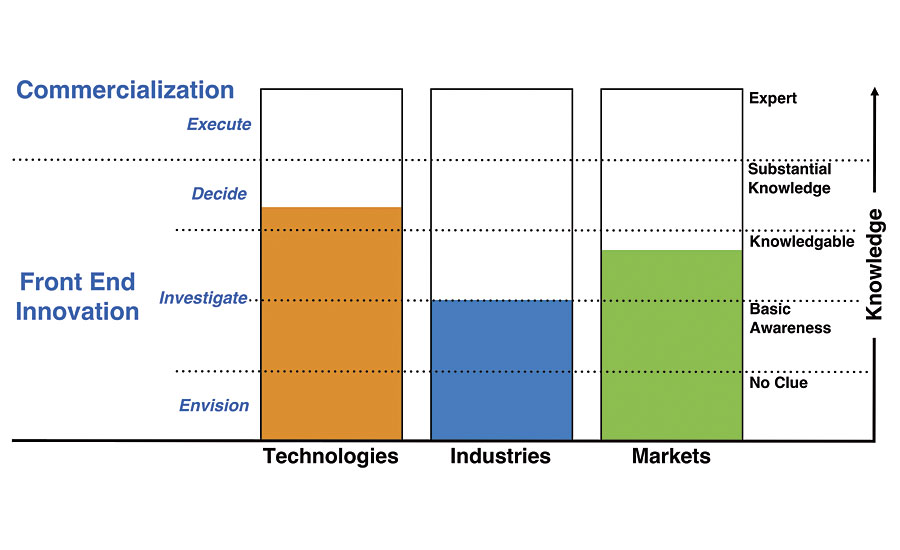

Now we move to the final GrowthPilot Key: work only critical uncertainties in the Front End. As you will recall from an earlier article (see Figure 4), our goal in any Front End project is, over time, to push our understanding of TIM (technologies, industries and markets) above the Substantial Knowledge line in each domain. We do this through a series of short projects, each designed to clear one (or maybe a couple) Critical Uncertainties (CU): the Front End is, in essence, a long series of short projects. The length of the process will depend on your starting knowledge level: for some projects it may take two years or more before a candidate that survives the process makes it into the market, but others - usually Core projects - may spend just a few weeks in the Front End.

The CU you should be working on is the one that the Engaged Executive determines is the single most important factor in making a decision about continuing the project. Be careful when choosing CUs to avoid this common problem: working on easy or familiar questions rather than the most important questions when considering additional investment of time or money in the project. What follows is additional guidance on choosing CUs.

For Envision Stage Projects (refer again to Figure 4), the most important questions often involve confirming market needs, growth rates, supply chains and similar, broad questions. These kinds of questions often require help from external innovation partners because you will generally be looking at markets and customers you are unfamiliar with: outside specialists may be able to significantly accelerate these early investigations.

Avoid - at this point and throughout the Front End - relying very much on “market reports.” For emerging markets, they are based on nothing but educated guesses and are often wrong. For established markets, the information may be solid, but it doesn’t provide any real insight into what that information means for your company. Just because a market is growing doesn’t mean it’s a good fit for you. Some example questions you might be considering at this stage include:

- Is this market large enough for us to care about?

- Is there a market entry point where we already have relationships or an ability to access the relevant channels?

- Do we have the technical and channel capabilities to effectively challenge existing competitors?

- Does our candidate solve an unmet market need?

- Do we need to be concerned about the IP position of existing competitors?

- Are there young companies in the space that may be working on solutions similar to what we have envisioned?

- Would it make sense to consider an acquisition as a path to market entry?

For Investigate Stage projects, picking CUs is more nuanced because what you need to know is getting more particular. The questions are not as broad, but - at the same time - may be more difficult or take more time to answer. Again, you should consider the use of external innovation partners to answer questions where you lack the internal expertise or it would take you too long to find the answer. Some example questions you might be considering at this stage include:

- What price-point is it likely that the market would accept for our envisioned project?

- Is it likely that we could manufacture the product at this cost?

- Do we have the ability to manufacture the product with our existing infrastructure? If not, what capital assets would we need to add and what would this cost?

- Will it be easy for likely competitors to respond to our innovation?

- What is the actual demand for our solution and how quickly can we expect to generate sales?

- What technical capabilities do we need to add to bring the envisioned project to market and how long will it take us to develop these capabilities?

- Are the raw materials we need to make this product readily available from existing suppliers? If not, can we develop the necessary relationships? Does the cost of these materials match our view of what end users might be willing to pay for the finished product?

For Decide Stage projects, picking CUs is straight forward: you are about to make a major funding decision, and you know what is required internally for decisions like this. Before you can complete this stage, you need all the information at hand to pass the Moment of Commitment: the CUs you choose are those that will allow you to accomplish this. Unlike the other phases, external innovation partners are seldom useful in the decision stage. The information you will need to pass the Moment of Commitment includes:

- A reliable calculation of ROI.

- A complete business plan.

Remember as you move through this process that your goal is to continually reduce uncertainty with each cleared CU. Choosing the right CU is important. Maintaining a steady, deliberate cadence of cleared CUs is important. Focusing on advancing through the stages is NOT important and, in fact, will often be counter-productive: advancement will happen naturally as you clear CUs, and it is impossible to predict how many there will be for any given project.

Also remember that there may very well be times when the Engaged Executive is directing work on multiple CUs simultaneously, but - and this is very important - a single team should never be working on more than one CU at a time. If multiple CUs are being worked, it should be through some combination of multiple teams/people and external innovation partners. For instance, if one team is working on a Customer Discovery exercise designed to narrow down the jobs-to-be-done for a group of potential end users, another might be working on an examination of technical feasibility.

When a team believes it has completed a CU investigation, the Engaged Exec should be notified. Often, but not always, the team will need to have a brief meeting with them to review the information gathered. Now the exec has a decision to make. This decision will be some combination of these possibilities:

- Ask for additional information. When you begin investigating a CU, the answer will sometimes be that you asked the wrong question. When this happens, you may need to keep the CU open, but modify it to take into account what you learned along the way.

- Intelligently halt the project. If the answer to the latest CU indicates that the project is not viable, stop the project and move on to the next one. But be open to pivoting if the original idea looks like a good one (more on this below) but the way you were thinking about implementing it turns out to be wrong. Stopping one project can sometimes lead immediately to starting another, but it can also involve taking a new direction with the original idea.

- Choose the next CU and continue work with the existing team. If you got an answer that demonstrates it is worth keeping the project alive, identify the next CU and evaluate your team. If they can answer the next one, keep going. If you need to bring on a person or two with different expertise for the next one, see the next possibility.

- Choose the next CU and augment the team with additional resources. If the next CU requires capabilities that you do not currently have on the team, add the resources you need whether additional internal personnel or external innovation partners.

- Engage the target Business Unit (BU). As an idea develops, it is going to become apparent over time (if it is not immediately apparent at inception) which BU will eventually take over the project to move it to commercialization, assuming it gets that far. After the completion of each CU, think about whether or not it’s time to get someone from the target BU involved. In general, BU involvement should start somewhere in the middle of the Investigate Phase when you have developed some confidence that the idea has real potential, but it could happen much sooner if a CU requires technical expertise that only resides within a BU. A project should never enter the Decide Phase without real BU involvement including executive briefings.

Repeat this process with the next CU until you move the project out of the Front End, across the MoC and into commercialization. Note that the project may transition into the BU prior to the Moment of Commitment if you get to the point where it appears all remaining CUs would be better answered by the BU rather than the Front End team that did the early-stage work.

A Review of all the Keys

Now it’s time for a quick review of all the keys. First, you need to make a commitment to balance your innovation portfolio with a deliberately chosen mix of core, adjacent and transformational initiatives. Next, you need to provide a protected adjacent/transformational innovation budget; if you fail to do this, the balancing you did won’t matter because near-term opportunities for core innovations will always take precedence over your riskier growth ideas aimed at new customers in new markets. The result will be predictable: mediocre organic growth and long-term risk to your company.

Once you have your portfolio goals in place and your budget secured, ensure that you manage projects differently in the Front End, the time before the Moment of Commitment in your stage gate process. Before the MoC, you are learning, and your metrics reflect that. After it you are executing, and the metrics change accordingly. This entire process will only produce the results you want if you work with an Engaged Executive who knows how to select the right team for Front End projects, basing staffing decisions on Front End aptitude rather than title or seniority. The Engaged Exec also has one additional task, and it may be the most critical: keeping the team focused so that they work only critical uncertainties, turning the Front End into a long series of short projects designed to gather the information necessary to make rolling invest/kill decisions.

As I’ve pointed out in earlier articles, we synthesized the GrowthPilot Keys by observing hundreds of new product development projects at global manufacturing companies and, at the same time, developing a deep understanding of the academic literature regarding the innovation challenges that big companies typically face. The keys work because they make you better at three critical tasks: (1) asking the right questions at the right time during new product development, (2) minimizing your spend (in time and resources) on ideas that are unlikely to find market success, and (3) delivering the data decision makers need to confidently make large investments in the best ideas. Adopt them at your company and you will put yourself on a path to sustained, predictable organic growth.

What to read next:

Achieving More Success in New Product Development

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!