The Moment of Commitment and the Engaged Executive

New Product Development Success Keys

The first and second articles in this series of four illuminated the new product development challenge and discussed the first two keys to sustained innovation success: maintaining a balanced innovation portfolio and a protected budget for innovation aimed at new markets and new customers. They provide helpful additional background for what is discussed in this article, and you can find them online at pcimag.com or in the December 2018 and March 2019 print editions.

The series is based on work my firm did over the last 15 years on hundreds of new product development projects at global manufacturing companies. In the course of that work we extracted six practical techniques that can help you achieve consistent, long-term revenue growth. The GrowthPilot keys work because they make you better at three critical tasks: (1) asking the right questions at the right time during new product development, (2) minimizing your spend (in time and resources) on ideas that are unlikely to find market success, and (3) delivering the data that decision makers need to confidently make large investments in the best ideas. This article will describe the third and fourth keys: managing product development efforts differently before and after what we call the Moment of Commitment, and the role of an engaged executive in the process.

As you may recall from earlier articles in this series, it is useful to think about three different kinds of innovation: core, adjacent and transformational. Core Innovation is making existing products better based on customer feedback, competitor activity and industry trends. Adjacent Innovation is aimed at selling genuinely new products to existing customers or selling existing (or slightly modified) products into genuinely new markets. Transformational Innovation involves creating genuinely new products aimed at new-to-the-company customers.

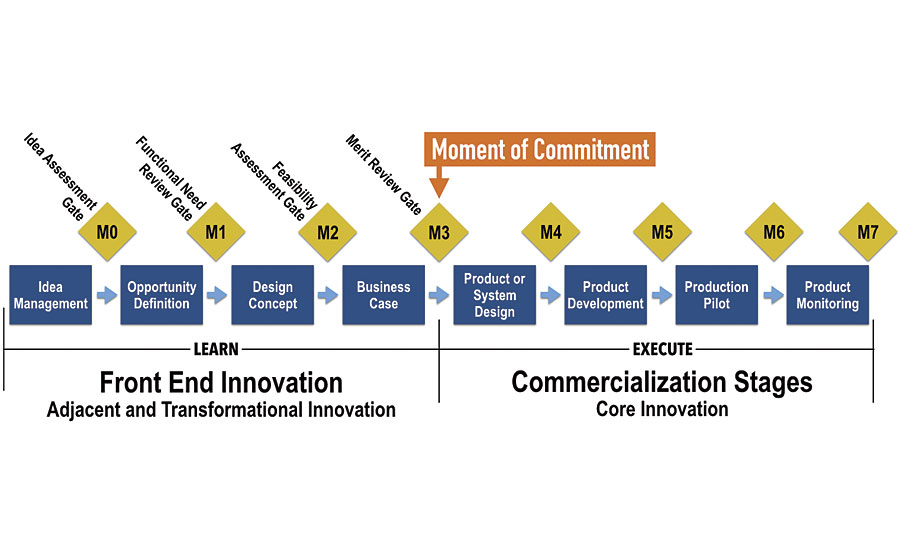

I’ll come back to the importance of these categories shortly, but we also need to review the Moment of Commitment (MoC) - this is our name for it, not a term of art - in a generic stage gate process similar to the one that is likely in use at your company (Figure 1). The stage gate process has steps, and one of these conceptually divides the new product development process from “we might launch this” to “we are absolutely launching this absent a major surprise.” This dividing line has two unique characteristics: (1) after the line (the MoC) you are going to expend substantial sums on getting the idea to market, and (2) you are willing to make these expenditures because you have a high degree of confidence in the product’s ultimate success.

Pre- and Post-MoC

Continuing to refer to Figure 1, before the MoC you are in what is referred to as the Front End, and you are learning. After, you are executing. But this is just in theory. In practice - at least at most companies - the way the stage gate is administered (no matter how it is described on paper), you are always executing and seldom learning. Why? Because executing is what big companies do well. In fact, it’s how they got big. So it’s natural that when a room is filled with people who have achieved success by executing, every new idea is going to be viewed through their execution lens.

Let’s take a look at the execution mindset in action so you can see what I am talking about. You have a major customer who said they need a new product that is essentially the same as one of your existing coatings with one exception: they want it to cure 20% faster. If you can do it, they say they will buy $5 million of it next year. Everyone is happy. You know an additive that will speed up the curing time, and - though it will take some experimentation - you are confident you can do it. The responsible exec immediately signs off on personnel assignments and budgets to make this important core innovation happen. The team is executing, and everyone is comfortable.

Now the conversation turns to an idea a chemist had about a new coating that will reflect UV radiation but allow other parts of the spectrum through. “Sounds interesting, but,” the responsible executive says, “there are a lot of questions that need to be answered. How much will it cost? Who will our first customers be? What will our margins look like? Will we be able to make it on our existing lines?”

These are all dumb questions because no one could conceivably answer them: it’s just an idea at this point. These are execution questions. But these are the questions the process - as poorly applied - comes to rely on because the company is addicted to low-risk activities. “Let’s put that one on the back burner,” says the exec, “We’ve got too many things to work on that we know customers want. We’ll talk about it more if you can come up with a business plan.” Nice idea, but you will never be able to come up with a business plan because learning what you need to know to build it will take some budget and a commitment to experimentation that will extend well beyond your next quarterly earnings call.

What would a good response to the idea be? A learning response. Imagine if the exec had instead said this: “Sounds interesting. Nose around a little bit over the next week and answer three broad questions for me. First, is there anything like that on the market today? Second, what are some potential applications for it? Third, what makes you think we might be able to do it? Don’t waste your time with a PowerPoint or anything. Just get a sense of the answer to those questions and we’ll talk again. If it looks like there might be a gap in the market, we’ll come up with a plan and a small budget to dig into it further.”

This, then, is a key difference between core innovation - on the one hand - and adjacent/transformational (a/t) on the other: companies are comfortable with core innovation because it fits naturally into an execution mindset, but uncomfortable with a/t innovation because, at the beginning, the focus is on learning rather than executing. I should note at this point that most core innovations spend some time in the late stages of the Front End because there are almost always uncertainties that need to be addressed: when 3M decided to start making Post‑it® Notes in new colors, it needed to make sure that the paper could take different dye colors, that the cost of the dye would maintain expected margins, etc. This was a classic example of a core innovation, but there were some Front End questions to address.

To solve this problem - the mismatch between the core innovation comfort zone and the mindset necessary to get a/t ideas to market - your company must develop the discipline to treat its new product development process in a fundamentally different way before and after the Moment of Commitment (MoC). It seems straight-forward, but, unfortunately, most companies don’t know this, don’t do it, and only get real organic growth when they get lucky or when a stubborn, committed innovator in the company relentlessly pursues an idea for years. If you want to change this dynamic, you have to change the way you think. Let’s return to 3M’s Post-it Notes to see how this can play out even at one of the most consistently innovative companies in the world.

In 1968, 3M’s Spenser Silver accidentally discovered the microsphere-based adhesive that eventually led to the Post-it Note. He was attempting to develop an ultra-strong adhesive to use in aircraft construction, but his prototype was a failure and delivered instead a pressure-sensitive adhesive that was too weak to be useful for anything. It was an interesting failure, though, because the adhesive could be removed from a surface without leaving any residue behind and could also be reused.

Sliver tried for years to find a use for the substance, but it wasn’t until 1974 that Art Fry - a 3M scientist working in another division who had heard one of Silver’s presentations - got the idea to put the adhesive on small pieces of paper so that he could keep them from falling out of his hymnal at choir practice. Upper management remained uninterested.

Silver, Fry and a more senior manager, Geoff Nicholson, kept pushing, roping in some colleagues who used their 15% time to develop a coating for the paper that would keep the glue attached to it, rather than leaving it behind on things after the note was removed. The iconic canary yellow paper was chosen, but this choice was also an accident: the lab next door had it lying around, so the team used it.

By now it was 1977, and the prototypes were popular enough around 3M’s campus that executives approved a test release in four cities under the name “Press ‘n Peel.” The goal: prove that it would be worthwhile spending the money for the company to redesign manufacturing machines to make the product at scale. The results were not encouraging; people didn’t understand what the notes were or how to use them. But, based on the love of the sticky notes by internal 3M users, the team continued to believe in the product. In 1979, they rebranded it as Post-it Notes and gave free samples to offices all over Boise, and that was the turning point: more than 90% of the offices reordered them, and the executive ranks finally understood that they had something special on their hands.

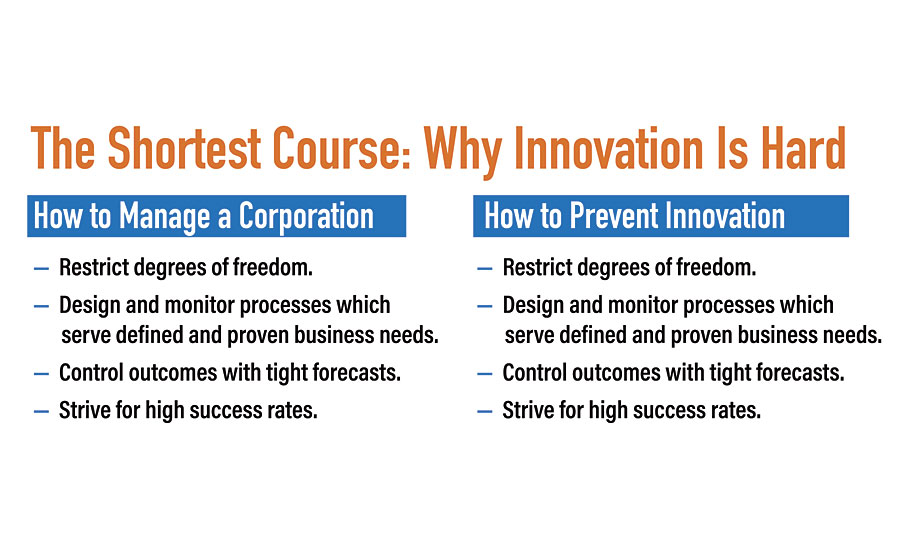

Today, more than 4,000 Post-it-branded 3M products are sold in 150 countries, more than 50 billion are produced each year, and annual revenue from the product crosses the $1 billion mark (a little more than 3% of this Fortune 100 company’s revenue). What is the lesson here? Geoff Nicholson - one of the co-inventors - summed it up: “We have a saying at 3M: Every great new product is killed at least three times by managers.” The same could be said for most companies: doing a/t innovation is hard because it’s hard to make the company really believe in a new product aimed at markets and customers the company doesn’t completely understand. The process to get from a single Post-it product to the bewildering variety sold today was straight-forward core innovation, but getting the first iteration into the market was a classic example of the a/t challenge: the things your company relies on to manage itself efficiently are the very things that destroy non-core innovation (Figure 2).

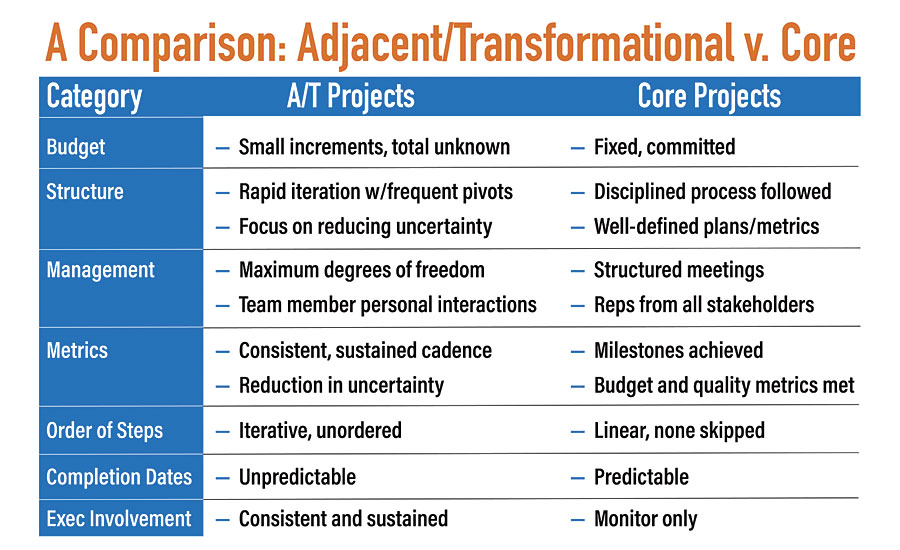

I’ve said that you can solve this challenge by treating projects differently before and after the MoC, but what does this mean in practice? It means that you must have a different mindset, different metrics, and, often, different people working on non-core projects before and after the MoC. Some of these differences are summarized in Figure 3 (and all will be discussed in greater detail in the next article in the series), but the short story is this: you must be flexible, prepared to pivot and prepared to kill a lot of projects pre-MoC; you must be exactly the opposite post-MoC.

The Role of Executives

Now let’s move on to the role of executives in the Front End. Management gurus from Peter Drucker to every lesser light that’s ever written a business book describe delegation as a core competency at the heart of every executive’s job. And this is certainly true. But not when it comes to the management of a/t innovation where over-delegation does more to damage to your chances of organic growth than any other variable.

Over the years, we’ve completed hundreds of Front End projects with our clients. Some of these companies were innovation pros and others were struggling. But despite the different innovation environments, the vast majority of the successful a/t projects had one thing in common: they produced interesting, actionable results, only where there was strong executive involvement. The reason for this is straight-forward.

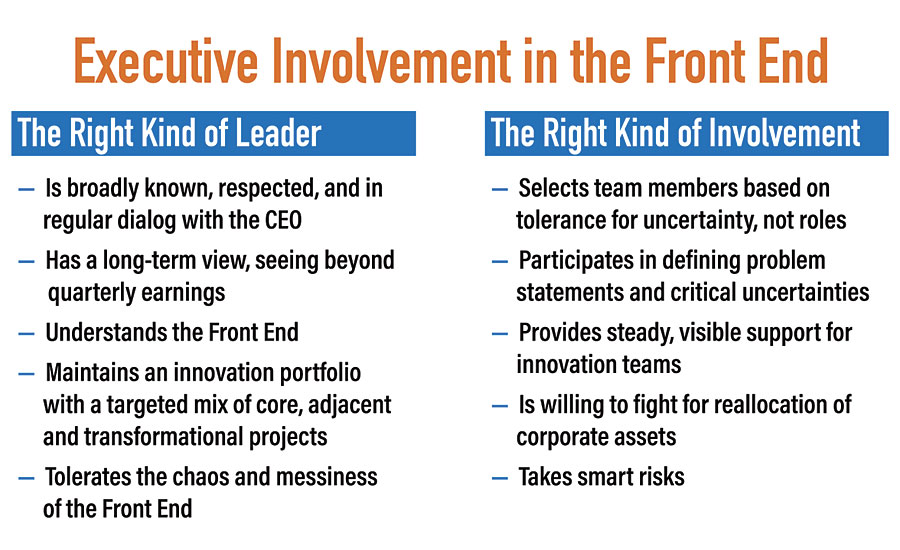

The outcome of the Front End process as applied to any single a/t idea is uncertain. Given this, executive support at the highest levels is absolutely critical: you must have someone committed to the process who understands the different focus of pre-MoC projects, grasps the necessity for rapid iteration and learning, and has the authority, sometimes under intense pressure, to maintain support for the process with vision, organizational clout, comfort with risk and, most importantly, resources (Figure 4). Said differently, if you fail to nourish your a/t project with strong executive leadership, the corporate immune system, which seeks out and destroys uncertainty at every turn, will starve it for resources when a near-term urgency for a core project arises (and it always does).

The executive participation needed by a/t projects is minimal: it’s the quality of your time rather than the quantity that matters. In the early stages of the Front End, there is a strong need for in-depth knowledge of a broad array of company competencies and of the company’s strategic goals. Using these perspectives, the executive should help guide the team about the questions that must be answered to prove the viability of the idea and allow further go/no-go decision-making. Without the executive perspective, team members may strike out in directions that sound good on paper but do not support the company’s long-term objectives, its capabilities or exploit its position in the competitive landscape.

Further, executive sponsorship at the early stages provides the team with critical, but sometimes overlooked, moral support. The core members of an innovation team are often working on a/t projects while continuing to execute on their every-day responsibilities; it’s important they know the company cares about the project, and there is no better way to demonstrate this than having a truly engaged executive sponsor. Finally, the engaged executive must also be the critical decision maker who understands and communicates that putting an evidence-based stop to a project is not a failure: getting to a smart “no” with a minimal expenditure of resources is a victory.

As the team moves farther along toward the MoC, the earlier strategic focus gives way to more mundane, but no less important, tasks: gathering the information necessary to make a decision about committing additional resources to the idea or quickly killing it off and trying something else. This is the phase where more team members may be drafted, and preparation begins for a potential commercialization push.

Finally, as you near the MoC, executive involvement is critical, direct and straight-forward. The team has gathered enough information to build a business case, and the executive must make a decision they are prepared to defend with the rest of the C-Suite. Go or no-go? Without this critical push right at the MoC, the chance that deeply promising, fully fleshed-out a/t initiatives cross the line is exceedingly slim.

Putting this all together, here are seven habits we’ve observed that belong to executives who are adept at innovation. They:

- Evaluate all innovation projects to separate core from a/t so they can put their focus in the right place.

- Recognize that over-delegation will destroy a/t initiatives and so engage with them personally.

- Select teams for the Front End with a focus on the right skills/mindset rather than making assignments based on roles or job titles.

- Ensure that teams have the resources required to rapidly develop the information necessary for rolling invest/kill decisions.

- Keep teams focused on reducing uncertainty rather than a final outcome.

- Keep project cadences rapid, understanding that the Front End is a long series of short projects.

- Banish failure from team and company vocabulary, maintaining a willingness to pivot, rethink, and intelligently halt initiatives when that is where the data leads.

Research and experience prove that the right kind of executive involvement is critical to a/t success. The Front End demands broad, strategic thinking in its early stages and bold, committed protection from the forces of the corporate immune response in its later stages, perspectives and power that only an executive can deliver. If your Front End process is not delivering the results you want, increasing smart, targeted executive involvement can make a big difference.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

-personnel-announcements-(1).webp?height=200&t=1681478349&width=200)