Using Simulation Tools and Physicochemical Properties to Guide the Selection of Pigment Dispersants, Part One

Theory

Davizro / iStock / Getty Images Plus, via Getty Images.

For the next few months, we will be discussing how we can use physicochemical properties as simulation tools to help choose the best additives. If you do a quick search, there are currently over 10,000 coatings raw materials and over 3,000 pigment dispersants used in coatings (numbers from an AI search of online chemicals for the coatings industry). So how can a formulator choose the best surfactant and then optimize their system? You can narrow down the selection by choosing dispersants designed for your pigment and system using the HLB (hydrophobe-lipophobe balance) and other criteria, but you will still be left with more dispersants than you can test. So what if you could use other criteria to narrow it down to a number you can actually test?

We will help by using some physicochemical constants — adsorption isotherms, free energy per unit area and Hansen solubility parameters — to make this choice easier. In this month’s column, I will cover some of the theory. Then we will move on to testing conditions and see how well these three parameters can help over the next few months.

The choice of a suitable dispersant is essential to provide an optimized dispersion of the pigment in water to minimize process time and energy costs. It will also maximize the pigment content in the formulation and ensure the stability of the pigment concentrate.

Simplified, the pigment dispersion process involves:

- Wetting the solid surface of the pigment.

- The physical separation of the pigment agglomerates during the dispersion and milling process.

- The stabilization of the pigments. Smaller particles generated are stabilized to avoid reagglomeration.

The choice of a suitable surfactant or surfactant system for pigment dispersion must consider its ability to reduce the surface tension during step (1) to facilitate the wetting of the pigment by water. It also must have the ability of its affinic group to adsorb onto the surface of the pigment quickly during step (2) to avoid the reagglomeration of the smaller particles generated. Finally, the choice of a suitable polymeric chain (tail) size — long enough to provide stabilization of the pigment particles but not harm the balance of intermolecular forces or reduce the adsorption of the affinic group on the pigment — must be considered during stage (3) of stabilization.

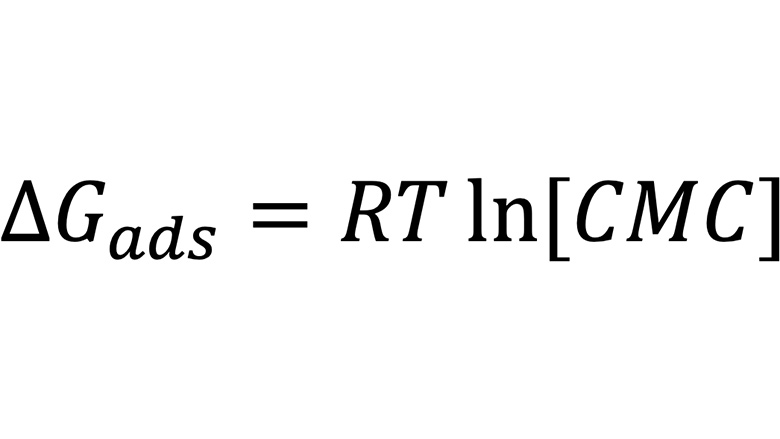

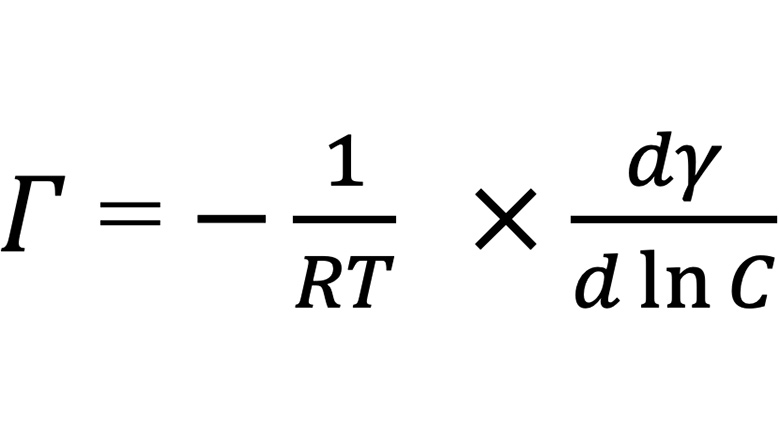

The use of physicochemical techniques and parameters can be applied to surfactants and can be utilized in the selection of wetting and dispersing agents. Based on simple surfactant parameters, such as critical micelle concentration, the free energy of adsorption of a surfactant can be calculated. Assuming that the free energy of adsorption liquid-vapor, when the surfactant organizes itself in the air-liquid interface, is similar to the free energy of adsorption liquid-solid, when the surfactant adsorbs onto a hydrophobic surface, Equation 1 can be used.

Equation 1 is very helpful to select the best hydrophobe over a set of different dispersants. The higher the free energy of adsorption, in module, the stronger the adsorption of the dispersant onto the pigment surface. However, to consider the hydrophilic portion of the dispersant and its size and structure when adsorbed, Equations 2 and 3 can be used.

Equation 2 is used to calculate the surfactant excess per unit area, and the product of the free energy of adsorption and the excess per unit area is called the surface free energy per area, which will greatly change as the size of the molecule changes. The higher the surface free energy per area, in module, the better the dispersant adsorption onto a hydrophobic pigment.

The correlation between the parameters discussed — such as static surface tension, dynamic surface tension, wetting time, contact angle and free adsorption energy — with performance and process properties in pigment concentrate formulations, such as deflocculation curves, process time, tinting strength, rub-out and stability, will be demonstrated.

The second part of the work is focused on the development of a method to create adsorption isotherms and on their use. This data is extremely valuable, as it allows for comparisons between additives from different technologies even when the chemical structure is unknown. Adsorption is a process governed by a series of forces and is generally the cumulative result of the forces of covalent bonds, electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, associative or repulsive interactions between adsorbate molecules and solvation.

To understand the adsorption phenomenon and the interactions between adsorbate and adsorbent, it is essential to establish the most appropriate correlation for adsorption in equilibrium, known as adsorption isotherm. Adsorption isotherms are generally expressed as the ratio of the adsorbate concentration in the solid to its concentration in solution at equilibrium. Several models for adsorption isotherms have been proposed over the years, and the physicochemical parameters and thermodynamic assumptions of each model allow the understanding of the adsorption mechanisms, the surface properties and the degree of affinity of the adsorbate with the adsorbent.

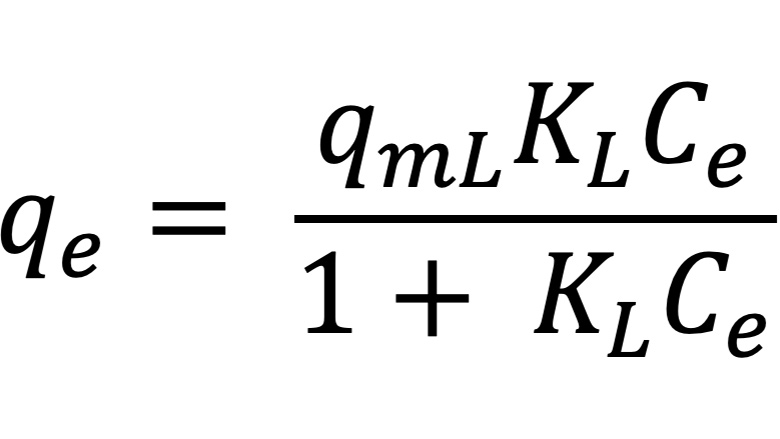

The Langmuir adsorption model was initially proposed for gas-solid adsorption, and its isotherm is characterized by saturation at high adsorbate concentrations. The model proposes the existence of adsorption sites on the surface of the adsorbent, and there is the premise that these sites are distributed homogeneously and the adsorption energy is constant. Langmuir establishes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the number of vacant sites and to the adsorbate concentration. The desorption rate is proportional to the number of occupied sites. Langmuir’s adsorption equation describes the amount of adsorbate on the adsorbent surface under equilibrium conditions.

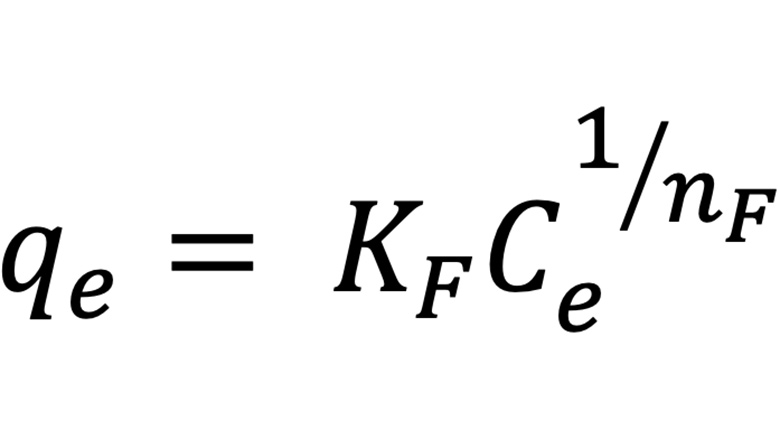

The Freundlich adsorption model is empirical and is not restricted to the formation of monolayers. The model proposes the existence of heterogeneous surfaces in which there are sites with high affinity and sites with low affinity. The sites with the highest affinity are quickly occupied by the adsorbate, which explains the abrupt growth in the amount of adsorbed material as a function of concentration at constant temperature. The occupation of the high affinity sites, added to a possible repulsion between the adsorbate molecules, explains the decrease in the amount adsorbed at higher concentrations, resulting in a concave isotherm profile. The equation that describes the Freundlich adsorption model is shown in Equation 5, where KF is the relative adsorption capacity constant, in L(1/n).mg(1-1/n).g-1 and nF is the heterogeneity factor, a dimensionless constant related to the adsorption intensity.

The study demonstrated how the curves and parameters obtained from this technique can help formulators understand which additive has higher affinity for a given pigment, aiding in the selection of dispersing agents with higher potential to provide good performance and longer stability. Additionally, this methodology helped with understanding the versatility of the additive, clarifying whether the same molecule could be used with different types of pigments.

The final part of the work aims to apply Hansen solubility parameters (HSP) to evaluate the compatibility of wetting or dispersing agents with pigments. The current focus is on using high-throughput screening to determine the HSP values of a variety of wetting and dispersing agents — such as surfactants and polymerics with or without charges. After the parameters of the additives and the pigments of interest are obtained, formulators could use these data to simulate the interaction between the additive and the pigment, enabling the selection of the most promising candidates for experimental evaluation.

The last goal of the work is to provide initial data on the HSP parameter determination and compatibility simulations to then correlate with experimental performance data of pigment concentrates, such as tinting strength, rub-out and stability. Once the correlation is proven, this methodology will allow a quick determination of parameters without requiring knowledge of the product’s composition and will aid the development of better coating formulation.

In the next few months, we will continue and prove these models performed well under our test conditions.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the contributions of Alann O. P. Bragatto, Suzy S. Alves, Beatriz Pinto, Rafael S. Dezotti, Robson Pagani, Bruno S. Dario and Fabricio G. Pereira. Their groundbreaking work and collaboration in this area have been instrumental to the development of this research.

This work was originally presented at the 2025 Waterborne Symposium and the 2025 Eastern Coatings Show, where it received Best Paper honors.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!